Image: Culture Wins

Image: Culture Wins

Charlie Sheen is not crazy. Or, at least, he’s not crazy the way you think he is. Charlie Sheen may finally be admitting that he’s lost his mind — exclusively to Life&Style, of all places, if we are to believe it — but that’s something that would have already been a long, long time in the making. What’s been happening over the past few weeks is not Charlie Sheen going crazy. Although it’s certainly easy to get confused. No doubt, Charlie Sheen wants you to think he’s crazy. After all, the boring recovering-addict Charlie Sheen Show — or the boring functioning-addict Charlie Sheen Show, depending on your preference — is much less interesting to watch than the “Crazy” one. And we are still watching….

In the course of this production it’s hard not to think about the film I’m Still Here, the cinéma vérité chronicling of Joaquin Phoenix’s “retirement from acting.”

.

For a year and a half, the twice Oscar-nominated Phoenix gained weight, stopped shaving, and tried to start a career as a rapper while his brother-in-law and fledgling filmmaker, Casey Affleck, came along for the ride to document this seeming descent into madness. Phoenix even famously came on Letterman in the course of I’m Still Here‘s production, disheveled and incoherent — an appearance that, by the end, prompted Letterman to say he owes an apology to Farrah Fawcett, til then considered his most disastrous guest of all time.

Of course, in the end it turned out this was not just another overindulged celebrity losing his mind. Nor, even after it was revealed that Phoenix’s “retirement” and subsequent actions weren’t exactly the plot of a straight “documentary,” was it all just simply a hoax. Back on the Late Show a year and a half later, now clean-shaven, and charming as usual, Phoenix explained:

We wanted to do a film that explored celebrity, and explored the relationship between the media and the consumers and the celebrities themselves. We wanted something that would feel really authentic. I’d started watching a lot of reality shows and I was amazed that people believed them; that they called them, like, ‘reality.’ I thought the only reason why is because it’s billed as being ‘real’ and the people use their real names. But the acting is terrible. I thought I could handle that. Because you don’t have to be very good. You just use your name, and people think that it’s real.

For a year and a half, Joaquin Phoenix lived the life of a character who shared his name and history and circumstances, both in private scenes and in the public eye. What then, truly, is the difference between what’s “real” and what isn’t? What does “hoax” even mean in the age of “reality TV?” I’m Still Here, along with the context around it, is a philosophical exploration of these questions.

It’s a very similar postmodern paradox that is at the heart of Banksy’s Exit Through The Gift Shop:

.

“The world’s first street art disaster movie” tells the story of Thierry Guetta, an eccentric French-born shop-keeper living in L.A. whose compulsive need to record every waking moment, and a cousin who happens to be the street artist Space Invader, combined to lead Guetta to become the de facto documentarian of the street art scene, tagging along on late-night art missions with its luminaries, including L.A.’s Shepard Fairey and, ultimately, the elusive reigning godfather of street art himself, Banksy. About two thirds of the way through the movie, Guetta, who had never previously edited any of the mountains of footage he’d been obsessively recording, goes to the U.K. to present a first draft of his “street art documentary” to Banksy for feedback. Deflecting his true opinion of the unwatchable film, Banksy suggests that perhaps Guetta should consider becoming a street artist himself and sends him back to L.A. with the idea of putting on a small show. Banksy also requests Guetta send him his raw video footage so that he can reedit it himself. And this is where the movie becomes something like an Andy Warhol adaptation of the Blair Witch Project.

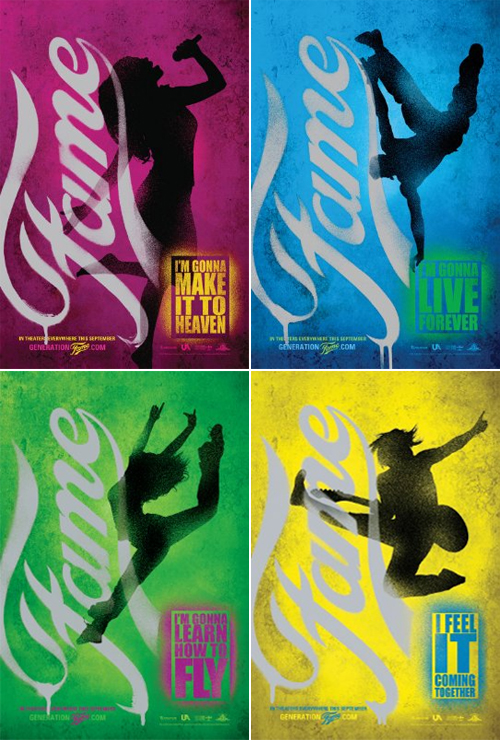

A few months before Joaquin Phoenix would be announcing his acting “retirement,” Guetta’s artist persona, Mr. Brainwash, or MBW, had moved from plastering L.A. with his own likeness — an image of a guy holding a video camera — straight to mounting a massive “street art” show, called “Life Is Beautiful,” in a 15,000 square-foot venue. Seemingly overnight, Mr. Brainwash was being positioned as an up-and-comer with the oeuvre of a Shepard Fairey or a Banksy — by then both artists, as well as many other leading names in the street art world, had begun having their art on display inside galleries as opposed to on the exterior of walls — except unlike these artists with years, even decades of creative evolution and refinement, Guetta had no experience. He’d hired an army of sculptors and designers to manufacture the pieces for his show, ripped straight from bookmarks in art books — even the illustration of Guetta holding the camera had been created by someone else.

The day of the show the line to get in stretched for blocks. Four thousand people attended the opening. By the end of the day nearly a million dollars worth of Mr. Brainwash art had been sold.

The story, at face value, seems so preposterous that the question of whether it could truly be real has dogged the film, as well as created the suspense that’s made it even more of a phenomenon. Could an amateur who’d never actually made art himself succeed at pulling off a show that so blatantly counterfeited and so quickly eclipsed those of the art form’s recognized heavyweights? And would they really release a movie about it happening? Or is all of it — the movie, Life is Beautiful, Mr. Brainwash — simply Banksy’s greatest prank yet? Theories abound. The New York Times labeled it as a harbinger of a new cinematic subgenre: The Prankumentary. “The whole thing, it’s clear now,” Fast Company insisted, “Was an intricate prank being pulled on all of us by Banksy, who has never publicly revealed his identity, with Fairey as his accomplice.” Their conjecture about what really happened: “Banksy… convinced Guetta to pose as a budding graffiti artist wannabe so he and Fairey could ‘direct’ him in real life — manufacturing a brand new persona.” Yet when asked at the end of the film how he feels knowing that he is in part responsible for Mr. Brainwash, Shepard Fairey laughs ruefully, “I had the best intentions. But sometimes even when you have the best intentions things can go awry…. The phenomenon of Thierry becoming a street artist, and a lot of suckers buying into his show and him selling a lot of expensive art very quickly, anthropologically, sociologically, it’s a fascinating thing to observe. And maybe there’s some things to be learned from it.” For his part, Banksy, even as his voice is scrambled beyond recognition, conveys unmistakable melancholy as he says, “I used to encourage everyone I met to make art. I used to think that everyone should do it….. I don’t really do that so much anymore.”

“This brutal and revealing account of what happens when fame, money and vandalism collide” could just be an L.A. story simply too bizarre to have been made up, and just as easily, it could all be a fabricated fable about what happens to an artistic movement when it becomes commercialized. From “selling out” to “cashing in” the concept is so mundane it’s a cliché, but Exit Through The Gift Shop‘s treatment is primarily to emphasize the absurdity of the progression of events rather than to make any concrete statement about them. As Banksy’s art dealer says at the end of the film, “I think the joke is on… I don’t know who the joke is on, really. I don’t even know if there is a joke.”

Which brings us back to Charlie Sheen. Not that what Sheen’s doing is any kind of joke or “prank.” This is all very much for real for him. And it is also a very deliberate performance. How did we get here? February 28, Charlie Sheen goes on Good Morning America, The Today Show, TMZ, Radar, Piers Morgan on CNN, 20/20 — basically, every celebrity interview news show he possibly can, and attracts a tsunami of flabbergasted attention for bein’ all ka-raaaazy. The next day he launches a social media empire.

Suddenly sounding not so crazy. Hell, as a digital strategist, I’d say it’s a pretty smart move. Within 25 hours and 17 minutes, Charlie Sheen had broken the world record for amassing 1 million Twitter followers faster than anyone else. Less than a week after his first tweet, he’d reached 2 million. “Another record shattered,” he tweeted, “We gobbled the soft target that was 2.0 mil, like a bag of troll-house zombie chow.” By then, he’d also launched a social media intern search:

which received over 74 THOUSAND! submissions in 5 days. Arguably no other celebrity has “gotten” the way social media works as fast. Even Conan had a slower uptake, though he’s undeniably provided a template for Sheen to work off of. (After getting canned from his TV job, Sheen did like MBW to Conan’s Banksy and announced he’s going on tour — the “Violent Torpedo of Truth/Defeat is Not An Option” Tour — just like Conan’s Banned From Television Tour last year in the wake of his own network debacle.) And, obviously, Sheen’s not doing it all on his own.

In Sheen’s 11-minute livestream episode, titled, “Torpedeos of Truth Part 2,” recorded on March 7th, 2011 — a week after his “old media” blitzkrieg — a terribly lit, grossly contrasted video in which a curmudgeonly, borderline belligerent Sheen looks like he might not have showered for days prior then rolled out of bed that morning, turned on his lap top, and started recording through the built-in camera above the screen, at 6 minutes, 40 seconds, when he ducks “below the frame line,” the camera moves. This is a recording made to look like it’s being done through a shitty built-in computer camera, but when it moves to follow Sheen as he ducks it’s suddenly clear there may be a camera person involved. If there is someone behind the camera, there could just as easily have been a lighting guy, a makeup person, but No! “Make me look as crazy as possible,” was clearly the direction here. By episode four it’d been announced that Sheen had officially been fired from his sitcom. The ante was upped. Suddenly Sheen, well-lit, made-up, looking as healthy as a marathoner — if not for the chain-smoking — in his sweat-wicking Nike shirt, was performing a soliloquy sounding like some misplaced Hunter S. Thompson diatribe. Clearly some writing talent may have been called in — if it hadn’t been already: consider that basically everything coming out of Charlie Sheen’s mouth becomes a meme — it’s been impossible to escape hearing someone say #winning (a hashtag in Charlie Sheen’s very first tweet) for weeks; then there’s #tigerblood, which is so meme-able it can’t even be summarized properly:

Tiger Blood Energy Potion found in a hotel lobby at SXSW Interactive. Photo: Danny Newman

Right now 4Chan, the primordial ooze that has spawned everything from lolcats to Rickrolling to SadKeanu to every other Internet meme you’ve ever heard of, is looking at Charlie Sheen like Woh. The last guy anywhere near this unstoppably memetastic was the Old Spice Guy–

and that guy was created by an AD AGENCY!

Something else you might notice — Charlie Sheen almost never swears. You have never heard him bleeped in any of the interviews he’s done on TV. There are no R-rated words on his Twitter stream. Every so often there’s some sprinkled in his livestreams, but for the most part The Charlie Sheen Show is all-ages. Where he could say “assholes” or “douchebags,” he says “silly fools” or “trolls.” These Playskool insults are unexpected, amusing, almost benign, yet nostalgically cruel. This is not the syntax of a man out of control.

“Where do these words come from, Charlie,” 20/20’s Andrea Canning asked.

“I don’t know,” he rolled his eyes, “They’re just words that sound cool together. Stuff just comes out and it’s entertaining and it’s fun and it sounds different from all the other garbage people are spewing, you know?”

Charlie Sheen doesn’t have Tourettes. He is deliberately saying these things to entertain and be funny and unique. And he’s good at it. Bret Easton Ellis — the author of Less Than Zero and American Psycho, as well as Lunar Park, a haunted house story in which the main character is a writer named Bret Easton Ellis who’s lived the same history as his eponymous creator (“It was always the A booth. It was always the front seat of the roller coaster. It was never ‘Let’s not get the bottle of Cristal’ … It was the beginning of a time when it was almost as if the novel itself didn’t matter anymore — publishing a shiny booklike object was simply an excuse for parties and glamour.”) or is it, rather, the life he was expected to have been leading? (“What was I doing hanging out with gangbangers and diamond smugglers? What was I doing buying kilos? My apartment reeked of marijuana and freebase. One afternoon I woke up and realized I didn’t know how anything worked anymore. Which button turned the espresso machine on? Who was paying my mortgage? Where did the stars come from? After a while you learn that everything stops.“) — writing in an article titled, “Notes on Charlie Sheen and the End of Empire,” calls Sheen, “the most fascinating person wandering through the culture:”

You’re completely missing the point if you think the Charlie Sheen moment is really a story about drugs. Yeah, they play a part, but they aren’t at the core of what’s happening—or why this particular Sheen moment is so fascinating…. This privileged child of the media’s sprawling entertainment Empire has now become its most gifted ridiculer. Sheen has embraced post-Empire, making his bid to explain to all of us what celebrity now means. Whether you like it or not is beside the point. It’s where we are, babe. We’re learning something. Rock and roll. Deal with it.

Post-Empire isn’t just about admitting doing “illicit” things publicly and coming clean—it’s a (for now) radical attitude that says the Empire lie doesn’t exist anymore, you friggin’ Empire trolls. For my younger friends, it’s no longer rare; it’s now the norm. To Empire gatekeepers, Charlie Sheen seems dangerous and in need of help because he’s destroying (and confirming) illusions about the nature of celebrity.

It’s thrilling watching someone call out the solemnity of the celebrity interview, and Sheen is loudly calling it out as the sham it is. He’s raw and lucid and intense…. We’re not used to these kinds of interviews. It’s coming off almost as performance art and we’ve never seen anything like it—because he’s not apologizing. It’s an irresistible spectacle. We’ve never seen a celebrity more nakedly revealing.

It’s the contradiction we could never quite reconcile in I’m Still Here or Exit Through The Gift Shop; one we can accept in Lady Gaga because she’s not using her real name and we’re sort of OK with it when it’s just a “character.” Charlie Sheen is real and not real at once: a spectacle and a revelation. It’s meta-postmodernism. It’s existential performance art. Minutes before Charlie Sheen’s first livestream was set to start, the audio feed came on. You could hear Sheen rehearsing the rant he would perform that night, prompting the question: is this all an act? Of course it is! He’s an acTOR. From a family of actors, who’s spent his entire life performing. There’s no way he’d go on camera ever without rehearsing. Charlie Sheen’s whole life has been a performance, and this now is not so much different, just with a bigger audience and, as we say in the 21st century music business, cutting out the middleman. As far as Charlie Sheen knows, this is what real is. And as far a we know that’s what it is, too.

Ellis writes:

If you can’t accept the fact that we’re at the height of an exhibitionistic display culture and that you’re going to be blindsided by TMZ (and humiliated by Harvey Levin, or Chelsea Handler—princess of post-Empire) while stumbling out of a club on Sunset Boulevard at 2 in the morning, then you should be a travel agent instead of a movie star. Being publicly mocked is part of the game, and you’re a fool if you don’t play along. This is why Sheen seems saner and funnier than any other celebrity right now. He also makes better jokes about his situation than most worried editorialists or late-night comedians.

What does shame mean anymore? my friends in their 20s ask. Why in the hell did your boyfriend post a song called “Suck My Ballz” on Facebook last night? my mom asks. But nothing yet compares to the transparency that Sheen has unleashed in the past two weeks—contempt about celebrity, his profession, the old Empire world order.

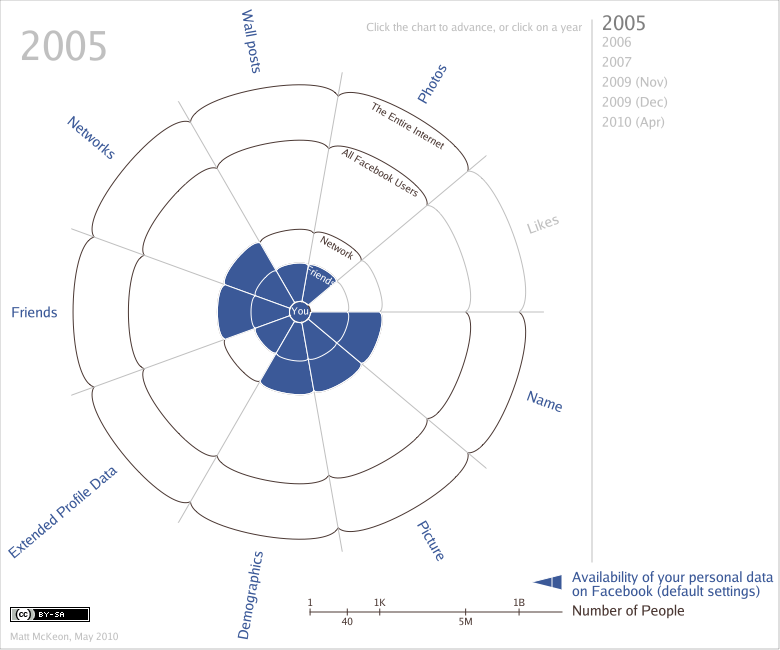

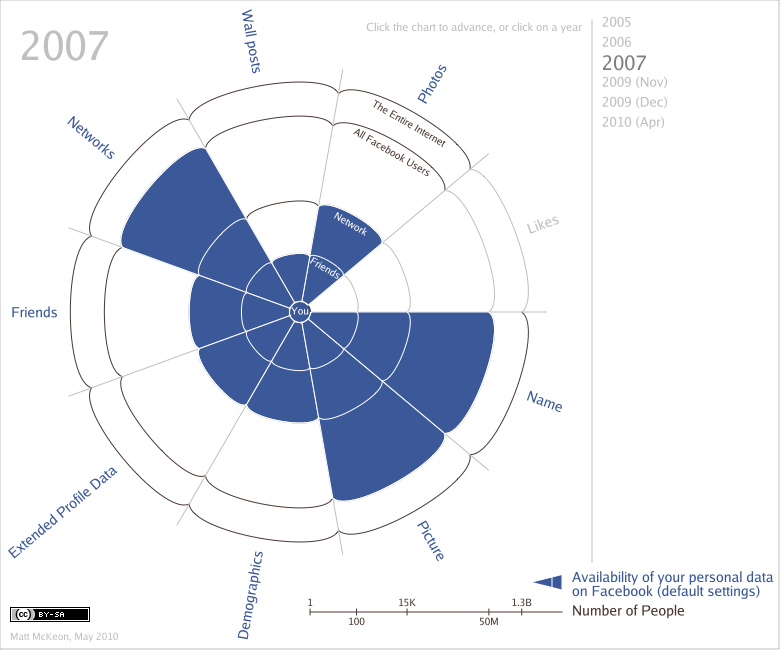

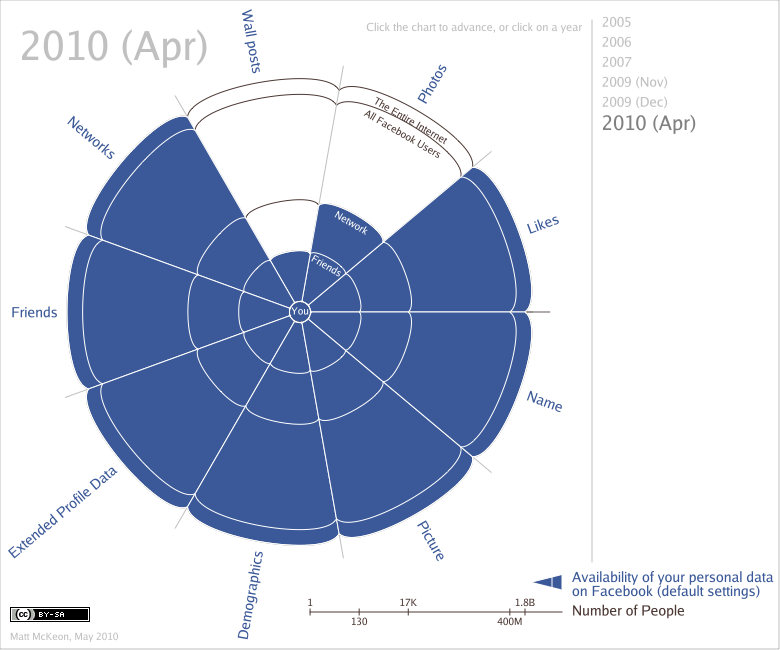

Ellis’s “Empire” is a reference to Gore Vidal’s definition of global American hegemony, which Ellis dates from 1945 until 2005: the era that defined the 20th century. Post-Empire is where we are now. For Ellis, Empire is the lie, the having to hide who you really are, the keeping up appearances; post-Empire, on the other hand, is what Ellis calls, “aggressive transparency.” But his perspective has one flaw: for Ellis, both Empire and post-Empire are binary. It’s one or the other. It’s true or it’s a lie; it’s real or its counterfeit. The post-Empire reality, however, is not the end of the lie, it’s the end of the binary. Sure, “radical transparency” has become a 21st century marketing buzzword. Sure, Mark Zuckerberg believes that Privacy is Dead and has remade Facebook in that image. Sure, I wrote last year, what makes Iron Man the first 21st century superhero? His lack of alter ego; his unconflicted, absolute identity. But that all is only part of the Millennial story.

Social media researcher danah boyd writes:

There’s an assumption that teens don’t care about privacy but this is completely inaccurate. Teens care deeply about privacy, but their conceptualization of what this means may not make sense in a setting where privacy settings are a binary. What teens care about is the ability to control information as it flows and to have the information necessary to adjust to a situation when information flows too far or in unexpected ways.

Just because teens choose to share some content widely does not mean that they wish all content could be universally accessible. What they want is a sense of control.

I’d argue this is, in fact, true of all of us now in the post-Empire. Not just teens. “What Sheen has exemplified and has clarified,” writes Ellis, “Is the moment in the culture when not caring what the public thinks about you or your personal life is what matters most—and what makes the public love you even more (if not exactly CBS or the creator of the show that has made you so wealthy).” Except that Charlie Sheen still very much DOES care. And so do all the rest of us in the 21st century. It’s there in every Facebook photo you’ve untagged yourself from. You had your reasons. It’s there in every location you pulled out your phone to check in at, and then decided not to. It’s there every time you hovered over, and then didn’t click the “Like” button. As tech blogger, Robert Scoble, writes:

The other day I found myself over at Yelp.com clicking “like” on a bunch of Half Moon Bay restaurants. After a while I noticed that I was only clicking “like” on restaurants that were cool, hip, high end, or had extraordinary experiences.

That’s cool. I’m sure you’re doing the same thing.

But then I started noticing that…. What I was presenting to you wasn’t reality.

See, I like McDonalds and Subway. But I wasn’t clicking like on those. Why not?

Because we want to present ourselves to other people the way we would like to have other people perceive us as.

I’d rather be seen as someone who eats salad at Pasta Moon than someone who eats a Big Mac at McDonalds.

This is the problem with likes and other explicit sharing systems. We lie and we lie our asses off.

Not only do we still care what other people think about us, we now curate it more obsessively. Trent Reznor calls it “A hyper-real version of yourself.”

This is the hyper-real version of Charlie Sheen. It is a role that Charlie Sheen is performing. And it is also who he actually is. Because how could he not be? Whatever Charlie Sheen does, that is who he is. This is the only way he has to take control over the flow of his information. For a celebrity in particular, as Ellis points out, that control is virtually non-existent. So how did Charlie Sheen wrest it back? By outdoing TMZ and the news shows and the magazines at their own game. He is no longer just a commodity of the tabloid industrial complex. He is the creator and star of his own show, the Crazy Charlie Sheen Show, and all the press is simply promotion.

Then again, it could be something much more simple. At Coachella 2008, Prince, headlining, kept demanding over and over, “Say my name, Coachella! Say my name, Coachella! Say my name, Coachella!” And like some epic call-and-response an ocean of 150,000 voices roared back: “Prince! Prince! Prince!” And I realized that if you’re Prince, there’s probably no way you can even get off anymore without 150,000 people screaming your name. Perhaps, if you’re Charlie Sheen, you can’t stay sober unless two million people are following your every move — just over two weeks after his first Tweet, it’s now closing in on 3 million.

“We’ve come a long way in the last two weeks,” Ellis concludes. “Sheen is the new reality, bitch, and anyone who’s a hater can go back and hang out with the rest of the trolls in the graveyard of Empire.” Like I’m Still Here and Exit Through The Gift Shop, what Charlie Sheen is doing is part of a continuum exposing the now inherent unreliability of the markers we’d previously depended on to tell the difference between what’s real and what isn’t. In some ways it’s as basic as the shift from the 20th century to the 21st; from analog to digital, from binary to exponential complexity. What, truly, does reality mean when it’s photoshopable? Or just another marketing campaign for some new movie? Not that reality doesn’t exist. Things are, out in the world; you can touch them. Earthquakes happen; nuclear reactors break; nations perch perilously on the verge of catastrophe. Reality exists, but it is no different from not reality. From the inscrutably contradictory government statements about radiation levels, from the fake Nuclear Fallout maps that spread like wildfire. Reality and not reality exist in the same plane now. It’s enough to make you go crazy. Unless you’re Charlie Sheen. In which case you’re not crazy. You simply are as your world is.

.