Art by: Sue Zola

I used to be pretty excited about technology. I’ve worked in social media since before the term existed; I co-created an app, I wrote pretty rah-rah-tech essays that people liked, like “Why Iron Man is the First 21st Century Superhero” (hint: his relationship to tech). I, like you, side-eyed wet blankets like Evgeny Morozov and Sherry Turkle and Jaron Lanier, like, sucks to be them; glad I don’t have their problem. Until, one day, I did. It started when I was writing Objectionable, and it never really went away. But perhaps nothing has made it feel quite as immersive as going to South By Southwest Interactive 2015.

The first time I went to SXSW was 8 years ago. The social web was a wild west where new and interesting things were emerging, and, unless you worked in music at the time, you probably didn’t give a shit. (Myspace was still the social network running everything, so don’t even). Twitter didn’t take off until, in fact, SXSW that year, and Facebook wouldn’t do anything at all even remotely relevant to brands until a few months later. At the time this was all a ghetto called “new media;” I had a title with the words “electronic marketing.” Since then, the tech startup industry has become a major, entrenched, cultural establishment, disrupting and colonizing other culture industries like entertainment and music. The SXSW festival, because it spans Music, Film, and Interactive technology, has come to occupy a unique position on the venn diagram of these 3 main influences of contemporary culture. So here’s a few snapshots from where we are in 2015.

MUSIC.

Pretty much all the highlights of my third SXSW trip that are fit to print, involve music, so we might as well just get the fun out of the way first.

Before I even got to Austin, the coolest flight I’ve ever had happened to me. I was seated next to an awesome, come up rapper from Miami, called Enoch da Prophet, whom you should listen to immediately:

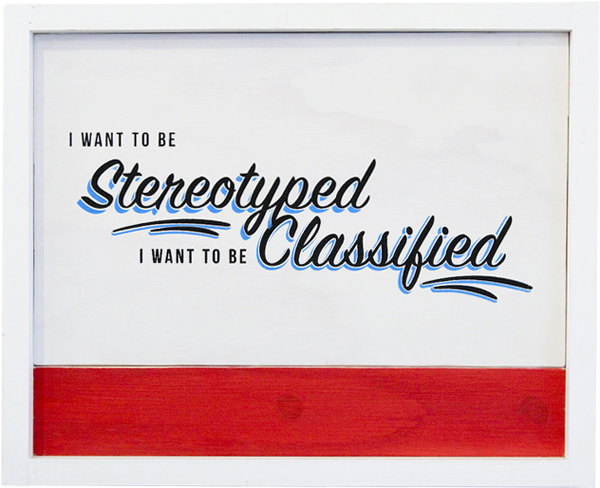

We talked for a bit about how the new generation of hiphop (J Cole, Kendrick, etc.), is rebelling against the violence, materialism, and other stereotypical “bullshit” of what’s become the established hiphop mainstream in order to define themselves and their own, new sound and vibe. If this is what the future of hiphop sounds like, I am soooo into it.

The moment I landed in Austin, my major evaluative criteria for which otherwise indistinguishable tech-sponsored parties to attend quickly turned out to be based entirely on music. There were parties with performances and / or DJ sets by Sir Mix-a-Lot, Busta Rhymes, Nas, The Flaming Lips, and more — all as part of Interactive. You could tell the difference between Interactive parties and Music parties because the former all had nostalgia-wave acts with name recognition among middle-aged marketing executives. By contrast, if the people on-stage and mostly everyone else are in their 20s and more interested in dancing than networking and the majority of the visible badges people are wearing around their necks have the word “STAFF” on them and the air smells like Swisher Sweets and hash, you can easily tell you’re at Music.

Mostly, the event that lived up to and exceeded the anticipation I had for it was Odesza at the Spotify House. It was their first time playing SXSW, and they were super adorable and excited and totally rocked the shit out of everything and got everyone goin’ up at 5 pm on a Tuesday.

Also fun was the party at the W with The Jane Doze, where my best friend, Jason, was managing a bunch of mermaids. Jason lives in Austin and co-runs Sirenalia, which creates custom, high-end silicone mermaid tails. The startup-sponsored party had hired a few of the mermaid performers to hang out in the pool and be generally Instagrammable.

Jason and I spent a lot of time talking about parenting in the age of social media, since Jason had just become a father 8 days prior. There’s a lot to consider now, like what your general philosophy is going to be about how you treat technology and content sharing, when the subject of said content is your progeny. Kids don’t get to “choose to be online now,” Jason says, “any more than they got to choose to have a mailing address.”

In retrospect, Music (and also music) turned out to be a welcome, transportive reprieve from the relentless grind of Interactive.

INTERACTIVE.

On the plus side of what I got to see as part of the official Interactive programming was a talk by Martin Harrison, Planning Director at Huge, entitled, “The Empathy Gap: Why Stalin Nailed Big Data.”

“One death,” Harrison quoted Stalin, “is a tragedy; one million is just statistics.” Basically, at a certain point the scope of violation becomes so massive that our minds kind of break at trying to comprehend it or calculate a just recourse. We literally can’t even. For example, in an experiment, people gave shorter jail sentences to food company executives who knowingly poisoned 20 people (4.2 years), than 2 people (5.8 years):

We'd give lesser sentences to crimes with more victims: it's harder to humanise numbers without a story #empathygap pic.twitter.com/XeWRU58JMs

— Gemma Milne (@gkmilne1) March 15, 2015

One of the most notable things about this talk was that it was so good even the questions asked by the audience at the end were legitimately interesting and extended the conversation (a phenomenon as unheard of as sitting next to someone relevant on an airplane). One of the questions was how can we institutionalize empathy within risk-averse organizations reliant on the dehumanizing safety-blanket of data? Harrison had some interesting thoughts about this, namely to do with having diversity among the decision-makers.

On the other side of the spectrum, I also went to a panel called Culture Clash: When Marketing and Product Converge, which I had actually been really interested in, not only personally, as this is the exact intersection of disciplines I’ve found myself straddling since launching Mirrorgram / SparkMode, but also from a macro, inter and intra-industry perspective. For marketing, this is the next big step in the evolution of the agency model — as Deutsch’s VP, Invention Director, Christine Outram says, “from ads that are designed to die, to ads that are designed to live” as products that people use every day. And for the product side, marketing is a critical capability to understand and embrace. What the ad world (at its best) has done for the length of its existence is seek to understand and leverage insights about human behavior. (“Happiness is a billboard on the side of the road that screams with reassurance that whatever you’re doing… it’s okay. You are okay.“) This human competency is necessary to surf the culture currents and capture lifestyle opportunities in a way that just features alone don’t.

Spoiler alert, the above paragraph is not what the panel was about at all. At least not the first 20 minutes of it, after which my friend, Rachel Rutherford, the Co-CEO of fashion startup, Pose, said we had to go. It was hard, she said, to listen to what marketing considered to be product successes.

“Welcome to how the other half lives,” I told her.

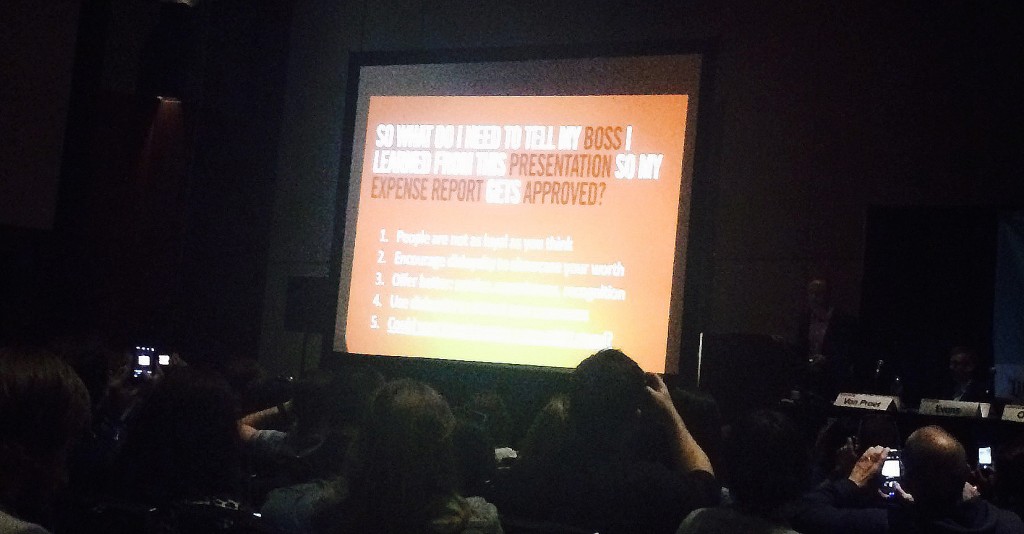

But that’s kind of how the whole premise of SXSW is flawed, though, isn’t it? Because so few things really are the kind of marketing or product successes we’re all claiming they are — in one day I managed to attend two different presentations that both referenced the now half a decade old, Old Spice Guy campaign. But you can’t sell a $1200 festival pass on the reality that most of what attendees are going to hear is aggrandized to sound amazing, to look epic, to seem important, to be Instagram-worthy. SXSW Interactive has a mass hallucination to uphold. And you’ve got an expense report to justify. One talk for real included a slide titled, “So what do I need to tell my boss I learned from your presentation so my expense report gets approved?” —

Ppl photo’d the shit out of that.

CULTURE.

One of the most jarring things that happened at SXSW was at the start of the Flaming Lips show sponsored by Spreadfast, which was super cool-looking and also had the feel of being deliberately reverse-engineered for Instagram. At one point, Wayne Coyne literally stopped a song and restarted it because the audience participation on the lyrics call-and-response wasn’t up to par for the optics “for YouTube.” Later, when I relayed this story to my friends they insisted that Coyne’s way too punk rock for the whole thing not to have been a joke, and maybe they’re right, but here’s the thing…. no one in the audience got it. This is 2015. We do as many takes as it takes to get something share-worthy. It’s not a joke; it’s where we are now as a culture.

Everything feels inescapably more cynical now. One night at a party at the Handlebar, I was talking to a couple of guys from San Francisco. I mentioned that I’d used to live there, and they asked me the standard followup, “Where?” But I shook my head and said, “The question isn’t ‘where,’ it’s ‘when?'”

I lived in San Francisco in 2000. It was a totally different city then than it is now, 15 years later. One of the guys from San Francisco was working at a new mobile search app, or whatever. (The goal being to take away even just .5% of Google’s market share. #Innovation!) He was describing the environment in San Francisco now. “You go out to cafes or anywhere, and it’s just” — he hunched over, smushing his arms against his chest like a Tyrannosaurus, fingers manically typing from flaccid wrists. “Meep, meep, meep,” he said in a robotic voice, completing the pantomime. Then he lowered his hands and confessed, “I’m shitting on the situation, but at the same time, I work in this industry.” He shook his head, sighed into his drink, “I’m part of the problem.”

Earlier, at the W party with the mermaids, Jason was wearing a sailor hat to complement the aquatic motif. A guy walked up to him, his eyes darting back and forth shiftily, his voice so conspiratorially low I could barely make out what he was saying; a question that seemed too absurd and sketchy to be real. Jason smiled carefully, and shook his head.

“Did he just ask to buy your hat off of you,” I said as we walked away.

“Yes.”

“Jesus. I thought he was looking for drugs.”

“I know.”

There was a relentless, transactional quality to SXSW Interactive interactions. You could imagine people picturing price tags floating above everyone’s heads like Sims character diamonds. Is that for sale? Is he for sale? Are they for sale?

I remembered an article I’d read a few months ago in Fortune, The Age of Unicorns, that began, “Stewart Butterfield had one objective when he set out to raise money for his startup last fall: a billion dollars or nothing. If he couldn’t reach a $1 billion valuation for Slack, his San Francisco business software company, he wouldn’t bother. It wasn’t long ago that the idea of a pre-IPO tech startup with a $1 billion market value was a fantasy. Google was never worth $1 billion as a private company. Neither was Amazon nor any other alumnus of the original dotcom class. Today the technology industry is crowded with billion-dollar startups. When Cowboy Ventures founder Aileen Lee coined the term unicorn as a label for such corporate creatures in a November 2013 TechCrunch blog post, just 39 of the past decade’s VC-backed U.S. software startups had topped the $1 billion valuation mark. Now, casting a wider net, Fortune counts more than 80 startups that have been valued at $1 billion or more by venture capitalists. And given that these companies are privately held, a few are sure to have escaped our detection. The rise of the unicorn has occurred rapidly and without much warning, and it’s starting to freak some people out.”

On my last day in Austin I heard about Jumpolin, a local piñata and bouncy house store, that was torn down to make space for parking for a South by Southwest tech party:

The morning of February 12, 2015, Austinite Sergio Lejarazu was driving past his small business, Jumpolin at 1401 E. Cesar Chavez Street, on his way to drop his daughter off at school. That’s when he noticed something strange. Jumpolin wasn’t there anymore. He pulled over and quickly learned that his new landlords, Jordan French and Darius Fisher, operating as F&F Real Estate Ventures, had demolished the building that Jumpolin occupied for eight years. The building still had all the inventory, cash registers and some personal property inside. Sergio and his wife Monica say they were given no prior warning and were up-to-date on their rent with a lease good until 2017.

In the end, the sponsor wound up moving the party to a different venue anyway due to the controversy. (Although not before one of the landlords managed to make an analogy to cockroaches in regards to his tenants.)

Reading about this happening — for a festival, for a party for all of the entitled, out-of-towner assholes like me and you and everyone we know in our badge-holder echo chamber — I felt gross. We are all sighing into our free drinks now; we’re all part of the problem.

Beyond the impact of its output, undoubtedly the most pathological impact technology has already had on our culture is economic. The increasingly stratified division between the people who make a living in some technology-adjacent field, and everyone else. And worse — the way people in technology treat “everyone else.”

When you ask people if they’re from Austin, the real locals consistently add the phrase “born ‘n raised.” My best friend is one of these people. He moved back to Austin after a stint in San Francisco came to an end when he was no longer able to afford to live there. Now he sees “the Google glass people” moving to his hometown, “and they have nothing to contribute to the culture except money.”

It’s beyond a cliche now to talk about how San Francisco has changed. Living in LA (where we don’t have a non-exploitable culture anyway, ha ha ha), I’ve heard the conversation about San Francisco turning into Monaco humming away up north in the distance. But in Austin, it felt very real and present and metastatic — it felt like everywhere else would be next.

If he couldn’t reach a $1 billion valuation, he wouldn’t bother… How much for your hat?… Is he for sale?… 20 people… 4.2 years….

One city gone is a tragedy. The rest is just statistics.

Mirrorgram by:

Mirrorgram by: