Because dressing different is such a cliché.

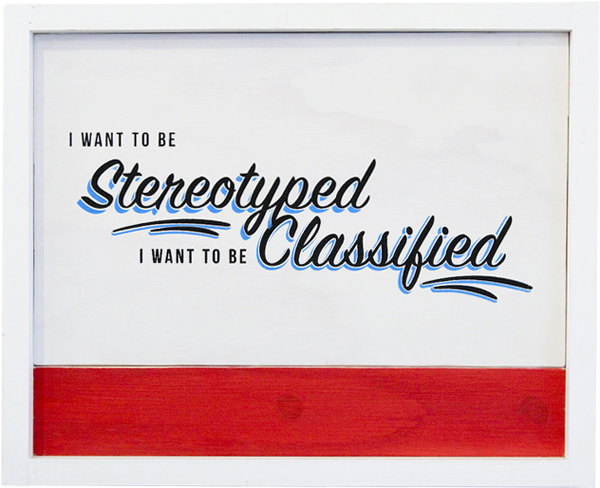

art by Curtis Mead

“The kids are doing the normcore,” my friend Quang said, trying out the new phrase with a deliberate, old fart dialect.

Only a few moments earlier I had tossed off the word like common parlance.

“‘Normcore?’” he had repeated, making sure he’d heard correctly.

“Yeah,” I explained, “It’s exactly what you think it is. It’s us, now.”

A shockingly pleasant March afternoon had arrived in Boston that day, on the heels of a cold that had felt like osteoporosis. A decade in LA had turned me into a wimp. I had forgotten how I’d ever managed to live through this in my youth.

I had grown up here. In high school I discovered raves. By college I was throwing them in 20,000 square foot warehouses in Dumbo. After that, I moved out to the west coast and managed a vaudeville circus troupe, produced electronic music festivals, and worked with a bunch of bands, among other things. In the span of the past decade I saw the niche “electronica” genre evolve into mainstream “EDM;” I saw the circus subculture infiltrate pop performance acts, and the signature, post-apocalyptic, tribal fashion aesthetic originated within the Burning Man community become a major fashion trend.

But that day in Boston, in 2014, hanging out with friends who had come up through the rave, circus, and goth subcultures, you could hardly tell where any of us had been. What we wore now was nondescript. Non-affiliated. Normal.

The week before, at a craft beer tasting party at an indie advertising agency in Silver Lake, a sculpture artist was remarking about recently looking through photos of style choices from the aughts. “What was I thinking,” she said in bewilderment. That evening she was wearing a black tank top, and, like, pants. Maybe three quarter length? Or not? Maybe black jeans? Or not-jean pants? I couldn’t recall. Perhaps, I thought, this was just a symptom of getting older. There was some kind of sartorial giving a shit phase that we had all grown out of. But it turned out this, too, was a trend. Kids, too young to have grown out of anything, were dressing this way.

“By late 2013, it wasn’t uncommon to spot the Downtown chicks you’d expect to have closets full of Acne and Isabel Marant wearing nondescript half-zip pullovers and anonymous denim,” wrote Fiona Duncan, in a February New York Magazine article titled, “Normcore: Fashion for Those Who Realize They’re One in 7 Billion:”

I realized that, from behind, I could no longer tell if my fellow Soho pedestrians were art kids or middle-aged, middle-American tourists. Clad in stonewash jeans, fleece, and comfortable sneakers, both types looked like they might’ve just stepped off an R-train after shopping in Times Square. When I texted my friend Brad (an artist whose summer uniform consisted of Adidas barefoot trainers, mesh shorts and plain cotton tees) for his take on the latest urban camouflage, I got an immediate reply: “lol normcore.”

Normcore—it was funny, but it also effectively captured the self-aware, stylized blandness I’d been noticing. Brad’s source for the term was the trend forecasting collective (and fellow artists) K-Hole. They had been using it in a slightly different sense, not to describe a particular look but a general attitude: embracing sameness deliberately as a new way of being cool, rather than striving for “difference” or “authenticity.”

Oh my god, I thought reading this: this is me.

In Nation of Rebels: Why Counterculture Became Consumer Culture, published in 2004, cultural critics, Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter examined the inherent contradiction in the idea that counterculture was an opposition to mass consumer culture. Not only were they not opposed, Heath and Potter explained, they weren’t even separate. Alternative culture’s obsession with being different — expressing that difference through prescribed fashion products and subcultural artifacts — had, in fact, helped to create the very mass consumer society the counterculture believed itself to be the alternative to.

“To me, Nike’s famous swoosh logo had long been the mark of the manipulated,” wrote Rob Walker, author of 2008′s Buying In: The Secret Dialogue Between What We Buy And Who We Are, ”A symbol for suckers who take its ‘Just Do It’ bullying at face value. It’s long been, in my view, a brand for followers. On the other hand, the Converse Chuck Taylor All Star had been a mainstay sneaker for me since I was a teenager back in the 1980′s, and I stuck with it well into my thirties. Converse was the no-bullshit yin to Nike’s all-style-and-image yang. It’s what my outsider heroes from Joey Ramone to Kurt Combain wore. So I found [Nike’s] buyout [of Converse] disheartening…. but why, really, did I feel so strongly about a brand of sneaker–any brand of sneaker?”

In response to Buying In, I’d written, “Whether we’re choosing to wear Nikes, Converse, Timberlands, Doc Martens, or some obscure Japanese brand that doesn’t even exist in the US, we’re deliberately saying something about ourselves with the choice. And regardless of how “counter” to whatever culture we think we are, getting to express that differentiation about our selves requires buying something.”

But that was five years ago. A funny thing happened on the way to the mid twenty-teens. The digital era ushered in an unprecedented flood of availability — of both information and products. This constant, ubiquitous access to everything — what Chris Anderson dubbed the “Long Tail” in his 2006 book of the same name – had changed the cultural equation. We had evolved, as Anderson predicted, “from an ‘Or’ era of hits or niches (mainstream culture vs. subcultures) to an ‘AND’ era.” With the widespread proliferation of internet access, mass culture got less mass, and niche culture got less obscure. We became what Anderson called a “massively parallel culture: millions of microcultures coexisting and interacting in a baffling array of ways.” On this new, flattened landscape, what was there to be counter to?

“Jeremy Lewis, the founder/editor of Garmento and a freelance stylist and fashion writer, calls normcore ‘one facet of a growing anti-fashion sentiment,’” Duncan writes in New York Magazine. “His personal style is (in the words of Andre Walker, a designer Lewis featured in the magazine’s last issue) ‘exhaustingly plain’—this winter, that’s meant a North Face fleece, khakis, and New Balances. Lewis says his ‘look of nothing’ is about absolving oneself from fashion.”

That is how normcore happened to me, too. When I quit the circus, leaving behind its sartorial regulations, I realized that difference wasn’t an expression of identity: it was a rat race.

“Fashion has become very overwhelming and popular,” Lewis explains in New York Magazine. “Right now a lot of people use fashion as a means to buy rather than discover an identity and they end up obscured and defeated. I’m getting cues from people like Steve Jobs and Jerry Seinfeld. It’s a very flat look, conspicuously unpretentious, maybe even endearingly awkward. It’s a lot of cliché style taboos, but it’s not the irony I love, it’s rather practical and no-nonsense, which to me, right now, seems sexy. I like the idea that one doesn’t need their clothes to make a statement.”

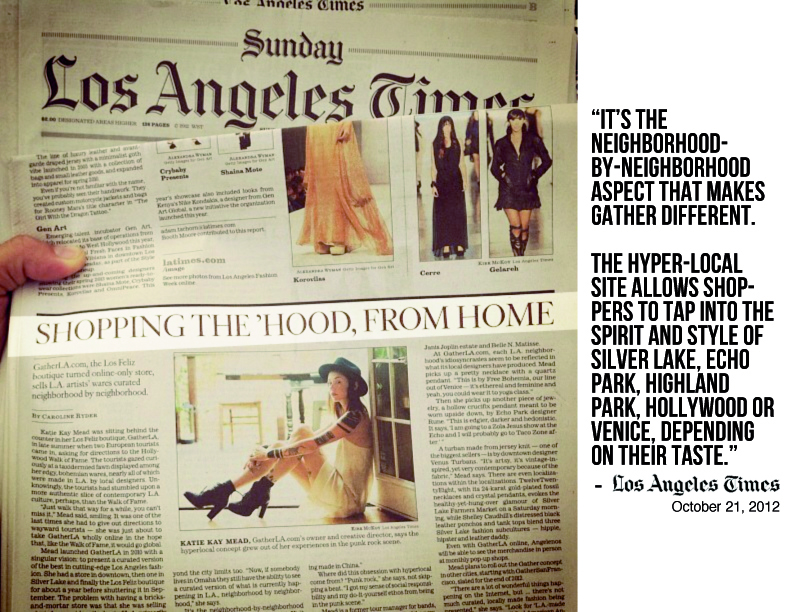

“Magazines, too,” Duncan writes, “have picked up the look:”

The enduring appeal of the Patagonia fleece [was] displayed on Patrik Ervell and Marc Jacobs’s runways. Edie Campbell slid into Birkenstocks (or the Céline version thereof) in Vogue Paris. Adidas trackies layered under Louis Vuitton cashmere in Self Service. A bucket hat and Nike slippers framed an Alexander McQueen coveralls in Twin. Smaller, younger magazines like London’s Hot and Cool and New York’s Sex, were interested in even more genuinely average ensembles, skipping high-low blends for the purity of head-to-toe normcore.

One of the first stylists I started bookmarking for her normcore looks was the London-based Alice Goddard. She was assembling this new mainstream minimalism in the magazine she co-founded, Hot and Cool, as early as 2011. For Goddard, the appeal of normal clothes was the latest thing. One standout editorial from Hot and Cool no. 5 (Spring 2013) was composed entirely of screenshots of people from Google Map’s Street View app. Goddard had stumbled upon “this tiny town in America” on Map sand thought the plainly-dressed people there looked amazing. The editorial she designed was a parody of contemporary street style photography—“the main point of difference,” she says, “being that people who are photographed by street style photographers are generally people who have made a huge effort with their clothing, and the resulting images often feel a bit over fussed and over precious—the subject is completely aware of the outcome; whereas the people we were finding on Google Maps obviously had no idea they were being photographed, and yet their outfits were, to me, more interesting.”

New media has changed our relation to information, and, with it, fashion. Reverse Google Image Search and tools like Polyvore make discovering the source of any garment as simple as a few clicks. Online shopping—from eBay through the Outnet—makes each season available for resale almost as soon as it goes on sale. As Natasha Stagg, the Online Editor of V Magazine and a regular contributor at DIS (where she recently wrote a normcore-esque essay about the queer appropriation of mall favorite Abercrombie & Fitch), put it: “Everyone is a researcher and a statistician now, knowing accidentally the popularity of every image they are presented with, and what gets its own life as a trend or meme.” The cycles of fashion are so fast and so vast, it’s impossible to stay current; in fact, there is no one current.

Emily Segal of K-HOLE insists that normcore isn’t about one specific aesthetic. “It’s not about being simple or forfeiting individuality to become a bland, uniform mass,” she explains. Rather, it’s about welcoming the possibility of being recognizable, of looking like other people—and “seeing that as an opportunity for connection.”

K-HOLE describes normcore as a theory rather than a look; but in practice, the contemporary normcore styles I’ve seen have their clear aesthetic precedent in the nineties. The editorials in Hot and Cool look a lot like Corinne Day styling newcomer Kate Moss in Birkenstocks in 1990, or like Art Club 2000′s appropriation of madras from the Gap, like grunge-lite and Calvin Klein minimalism. But while (in their original incarnation) those styles reflected anxiety around “selling out,” today’s version is more ambivalent toward its market reality.

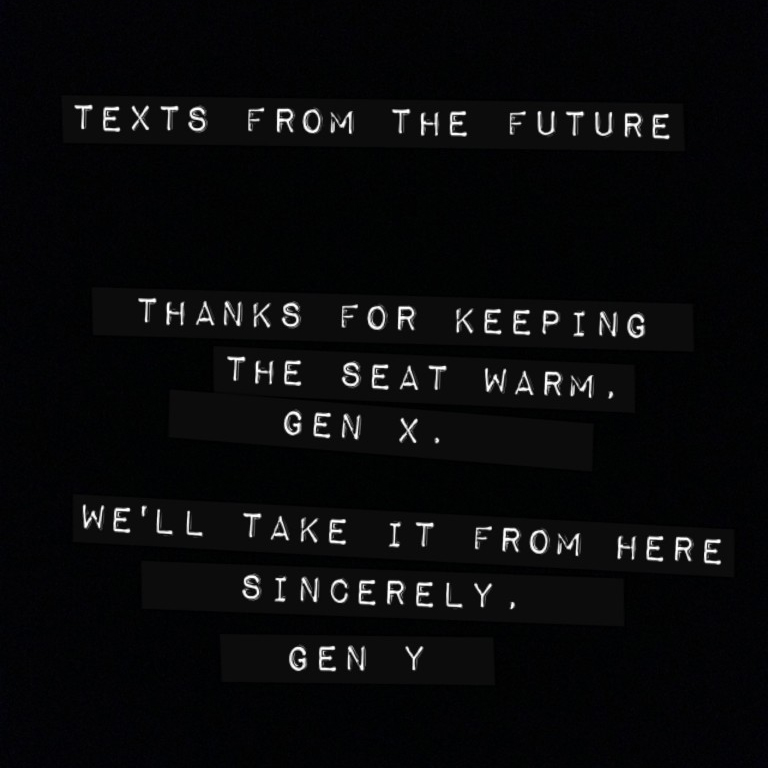

In a post Hot-Topic world, where Forever21 serves up fast fashion in processed flavors like, Occupy:

we’re realizing that alternativeness, as a means for authentic self expression, is futile.“Normcore isn’t about rebelling against or giving into the status quo,” Duncan concludes, “It’s about letting go of the need to look distinctive.”

In our all-access, always connected, globalized world, obscurity is scarce. When everything is accessible, nothing is alternative.

“In the 21st century,” Rob Walker wrote back in 2008, not recognizing the quickly approaching end of counterculture, “We still grapple with the eternal dilemma of wanting to feel like individuals and to feel as though we’re apart of something bigger than ourselves. We all seek ways to resolve this fundamental tension of modern life.”

In 2014, normcore is one solution we’ve found to resolve it.

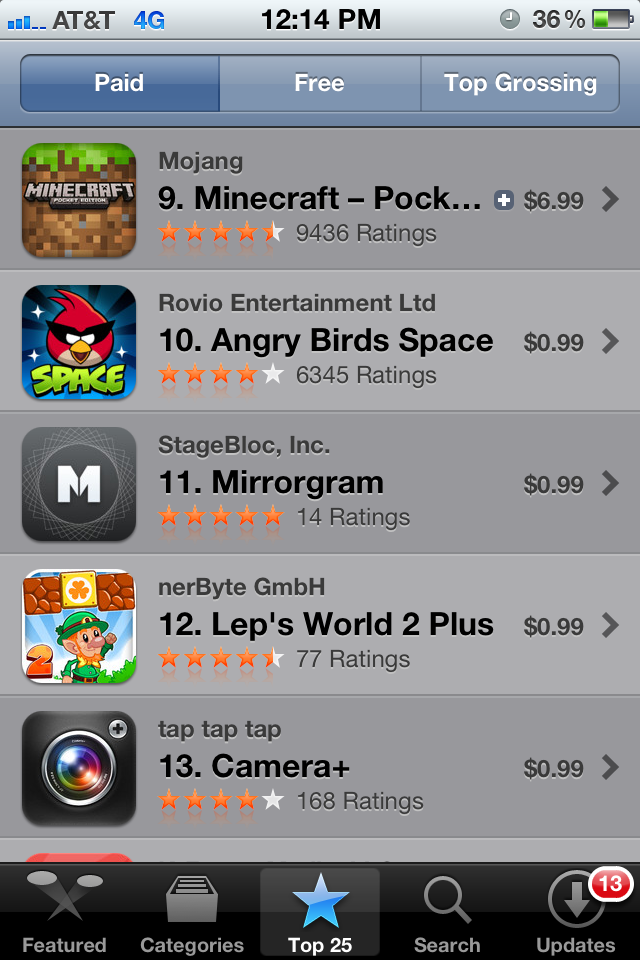

Mirrorgram by:

Mirrorgram by: