A musician friend of mine was once seeing the best friend of a famous heiress and he told me this story: “I had been dating her for a month and one night she invited me out to go meet her whole crew for the first time. I was SUPER nervous. Meeting the group of friends of someone you’re dating for the first time can be nerve-racking anyway, but especially if they are like…. that. I drove there and I was standing outside like, ‘OK… I need to get my shit straight and go in there and own this place.’ All of a sudden it hit me: ‘Channel your inner Tony Stark!'” It worked, he said, “Game over.”

Hearing this story, I wondered, who was my inner spirit superheroine? What clever badass would I conjure for existential ammo in a situation like this? I started searching my mental pop culture database for an acceptable candidate and this is when I realized I could barely think of a single one. The only two vaguely applicable options coming to mind were both from a decade ago: Buffy foremost, and, more hazily, Trinity. But Buffy’s final episode had aired, and Trinity had devolved from enigma to boring love interest saved by her boyfriend at the end of the Matrix trilogy, both back in 2003. As far as contemporary, mainstream, pop culture was concerned, there was a giant void.

I turned to the Internet for help, and found a list of the 100 Greatest Female Characters, compiled by Total Film. While not exactly rigorous in its methodology (fully 6% of the list’s alleged 100 greatest female characters are not actually human; 3 — Audrey 2 from Little Shop of Horrors, Lady from Lady and the Tramp, and Dory from Finding Nemo — aren’t even humanoid), the audit is, at the very least… directional. Narrowing the list down to just those heroines who’ve graced the big screen within the past 10 years (minus the non-human entries) the chronological order looks like this:

- #7: Hermine Granger (Harry Potter series – 2001 to 2011)

- #45: Paikea Apirana (Whale Rider – 2002)

- #65: Lee Holloway (Secretary – 2002)

- #8: The Bride / Beatrix Kiddo (Kill Bill – 2003 to 2004)

- #44 Charlotte (Lost In Translation – 2003)

- #4 Clementine Kruczynski (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – 2004)

- #43 Ofelia (Pan’s Labyrinth – 2006)

- #99 Cherry Darling (Planet Terror – 2007)

- #11 Eli (Let the Right One In – 2008)

- #30 Kym (Rachel Getting Married – 2008)

- #13 Lisbeth Salander (The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo – 2009 t0 2011)

- #36 Older Daughter (Dogtooth – 2009)

- #38 Mia Williams (Fish Tank – 2009)

- #26 Nina Sayers (Black Swan – 2010)

- #40 Mindy “Hit Girl” Macready (Kick-Ass – 2010)

Among these 15 possible spirit superhoreine candidates there are 6 victims of sexual abuse, 3 are dealing with some form of depression, 4 haven’t hit puberty, 2 are addicts — including one vampire — and, most notably, a full third who would sooner slaughter a party than charm it. New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis observed this trend last year, writing:

It’s no longer enough to be a mean girl, to destroy the enemy with sneers and gossip: you now have to be a murderous one. That, at any rate, seems to be what movies like Hanna, Sucker Punch, Super, Let Me In, Kick-Ass and those flicks with that inked Swedish psycho-chick seem to be saying. One of the first of these tiny terrors was played by the 12-year-old Natalie Portman in Luc Besson’s neo-exploitation flick The Professional (1994). Her character, a cigarette-smoking, wife-beater-wearing Lolita, schooled by a hit man, was a pint-size version of the waif turned assassin in Mr. Besson’s Femme Nikita (1990), which spawned various imitators. Mr. Besson likes little ladies with big weapons. As does Quentin Tarantino and more than a few Japanese directors, including Kinji Fukasaku, whose 2000 freakout, Battle Royale, provided the giggling schoolgirl who fights Uma Thurman’s warrior in Kill Bill Vol. 1. Mr. Tarantino and his celebrated love of the ladies of exploitation has something to do with what’s happening on screens. Yet something else is going on…. The question is why are so many violent girls and women running through movies now.

That question is particularly pointed since this genre is not exactly blockbuster material. Hanna was only slightly profitable. Sucker Punch flopped, as did Haywire and the Besson-produced, Colombiana; both Kick-Ass and Let Me In were “gore-athons that movieplexers don’t want to see,” and, in spite of all its hype, the American remake of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo was a “huge box office disappointment.” And that’s all just in the past two years.

In an April, 2011, New Yorker article titled, “Funny Like A Guy, Anna Faris and Hollywood’s Women Problem,” Tad Friend wrote:

Female-driven comedies such as Juno, Mean Girls, The House Bunny, Julie & Julia, Something’s Gotta Give, It’s Complicated, and Easy A have all done well at the box office. So why haven’t more of them been made? “Studio executives think these movies’ success is a one-off every time,” Nancy Meyers, who wrote and directed Something’s Gotta Give and It’s Complicated, observes. “They’ll say, ‘One of the big reasons that worked was because Jack was in it,’ or ‘We hadn’t had a comedy for older women in forever.”

Amy Pascal, who as Sony’s cochairman put four of the above films into production, points out, “You’re talking about a dozen or so female-driven comedies that got made over a dozen years, a period when hundreds of male-driven comedies got made. And every one of those female-driven comedies was written or directed or produced by a woman. Studio executives believe that male moviegoers would rather prep for a colonoscopy than experience a woman’s point of view. “Let’s be honest,” one top studio executive said. “The decision to make movies is mostly made by men, and if men don’t have to make movies about women, they won’t.”

Except, it seems, if those women happen to be traumatized, ultra-violent vigilantes of some sort. Perhaps these movies keep getting made because their failure is seen as a one-off every time, too.

“Men just don’t understand the nuance of female dynamics,” Friend quotes an anonymous, prominent producer. Although the conversation is about comedy (why men can’t relate to Renee Zellweger in Bridget Jones, for example), it could explain why all these vengeful heroines seem to inevitably wind up defective. This violent femmes sub-genre — which expands the traditional Rape/Revenge archetype to also encompass psychologically violated prepubescents — by default demands female protagonists. But since their creators don’t understand how to make them, they stick to what they know. Consider that the title role in Salt was originally named Edwin, and intended for Tom Cruise before she became Evelyn and went to Angelina Jolie. The emotionally stunted, socially inept, tech savant protagonists of David Fincher’s two latest films — male in The Social Network, female in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo — are equally as interchangeable. From Hannah to Hit Girl, all the way back to Matilda in The Professional, it’s always been a father, or father figure who’s trained them. A woman, this narrative suggests, would have nothing to offer in raising a powerful daughter. When a film needs a Violent Femme the solution has become to simply write a man, and then cast a girl. (Failing that, just mix up a cocktail of disorders — Asperger’s, attachment disorder, PTSD; a splash of Stockholm Syndrome — where a character needs to be.) No understanding of female dynamics required.

“What if the person you expect to be the predator is not who you expect it to be? What if it’s the other person,” asks producer, David W. Higgins, on the DVD featurette for his 2005 film, Hard Candy, about a 14-year-old girl, played by Ellen Paige, who blithely brutalizes a child molester. Whereas for 20th century heroines like Princess Leia (#5 on Total Film’s 100 Greatest Female Characters), Sarah Connor (#3), or Ellen Ripley (#1 — of course), not to mention their brethren, overcoming trauma is what made them become heroes, for this new crop, trauma is what excuses them from seeming like villains in their own right. We love to see the underdog triumph, but do we really want to watch a victim become the predator, and a predator become the hero? The ongoing failures of films fetishizing this scenario suggest we’re just not that into this cognitive dissonance.

So much for movies no one wants to see, but what about those those every girl has? On the one hand there’s Twilight, whose Bella Swan is a dishrag of a damsel in distress so useless her massive popularity is a disturbing, cultural atavism. On the other, there’s the Harry Potter series, whose Hermione Granger (#7) might be “The Heroine Women Have Been Waiting For,” according to Laura Hibbard in the Huffington Post. “The early books were full of her eagerly answering question after question in class, much to the annoyance of the other characters. In the later books, that unapologetic intelligence very obviously saves Harry Potter’s life on more than one occasion. Essentially, without Hermione, Harry wouldn’t have been ‘the boy who lived.'” Meanwhile, here’s how Total Film describes Leia: “Royalty turned revolutionary, a capital-L Lady with a laser gun in her hand. Cool, even before you know she also has Jedi blood.”

And that is the one, simple, yet infinitely complex element that is consistently missing across the entire spectrum of stiff, 21st century downers: Cool. “Of all the comic books we published at Marvel,” said Stan Lee, the creator of Iron Man, Spider-Man, the Hulk, the X-Men, and more, “we got more fan mail for Iron Man from women than any other title.” Cool is the platonic ideal Tony Stark represents. It’s what makes him such an effective spirit superhero for the ordeal of party. But while Stark may be special he’s not an anomaly. From James Bond to Tyler Durden, male characters Bogart the cool. And it’s not because they’re somehow uniquely suited for it (see: the femme fatale). It’s because their contemporary female counterparts are consistently forced to be lame.

“You have to defeat her at the beginning,” Tad Friend quotes a successful female screenwriter describing her technique. “It’s a conscious thing I do — abuse and break her, strip her of her dignity, and then she gets to live out our fantasies and have fun. It’s as simple as making the girl cry fifteen minutes into the movie.” That could just as easily describe Bridesmaids as The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo. Which is totally fucked, first of all. And secondly, it’s boring. You’d think there’d be more narrative to go around — though I suppose I did just see the once female-driven Carrie, and The Craft remade as an all-male superhero origin flick called, Chronicle. Perhaps we really have reached Peak Plot. In which case now would really be the time to be R&Ding some alternatives.

“I love to take reality and change one little aspect of it, and see how reality then shifts.” said director, Jon Favreau. “That was what was fun about Iron Man, you [change] one little thing, and how does that affect the real world?” Favreau’s experiment has yielded a superhero archetype that reflects a slew of Millennial mores, from the intimacy of his relationship with his gadgets, to his eschew of a secret identity in favor of that uniquely post-digital virtue of radical transparency, to his narcissism. “If Peter Parker’s life lesson is that ‘with great power comes great responsibility,'” I wrote in a post titled, Why Iron Man is the First 21st Century Superhero, “Tony Stark’s is that with great power comes a shit-ton of fun. Unlike the prior century’s superhero, this new version saves the world not out of any overwhelming sense of obligation or indentured servitude to duty, but because he can do what he wants, when he wants, because he wants to. Being Iron Man isn’t a burden, it’s an epic thrill-ride.” Breaking with the established conventions of the genre to create a uniquely modern superhero has made Iron Man a success, to the tune of a billion dollar box office between the two movies, and launched Marvel Studios and ensuing Avengers’ franchises in its wake. But there’s one 21st century shift Tony Stark will never be able to embody. And it’s kind of a big one.

From The Atlantic Magazine:

Man has been the dominant sex since, well, the dawn of mankind. But for the first time in human history, that is changing—and with shocking speed.

In the wreckage of the Great Recession, three-quarters of the 8 million jobs lost were lost by men. The worst-hit industries were overwhelmingly male and deeply identified with macho: construction, manufacturing, high finance. Some of these jobs will come back, but the overall pattern of dislocation is neither temporary nor random. The recession merely revealed—and accelerated—a profound economic shift that has been going on for at least 30 years, and in some respects even longer.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women now hold 51.4 percent of managerial and professional jobs—up from 26.1 percent in 1980. About a third of America’s physicians are now women, as are 45 percent of associates in law firms—and both those percentages are rising fast. A white-collar economy values raw intellectual horsepower, which men and women have in equal amounts. It also requires communication skills and social intelligence, areas in which women, according to many studies, have a slight edge. Perhaps most important—for better or worse—it increasingly requires formal education credentials, which women are more prone to acquire, particularly early in adulthood.

To see the future—of the workforce, the economy, and the culture—you need to spend some time at America’s colleges and professional schools, where a quiet revolution is under way. Women now earn 60 percent of master’s degrees, about half of all law and medical degrees, and 42 percent of all M.B.A.s. Most important, women earn almost 60 percent of all bachelor’s degrees—the minimum requirement, in most cases, for an affluent life. In a stark reversal since the 1970s, men are now more likely than women to hold only a high-school diploma.

American parents are beginning to choose to have girls over boys. As they imagine the pride of watching a child grow and develop and succeed as an adult, it is more often a girl that they see in their mind’s eye.

Yes, the U.S. still has a wage gap, one that can be convincingly explained—at least in part—by discrimination. Yes, women still do most of the child care. And yes, the upper reaches of society are still dominated by men. But given the power of the forces pushing at the economy, this setup feels like the last gasp of a dying age rather than the permanent establishment. It may be happening slowly and unevenly, but it’s unmistakably happening: in the long view, the modern economy is becoming a place where women hold the cards.

That view makes even comedian (and father of two daughters) Louis C.K.’s pronouncement in a recent Fast Company article that “The next Steve Jobs will be a chick” not unimaginable. And when she is, who will be her inner superheroine? Any of the girls brandishing medieval weaponry headed, like crusaders, for movie theaters this year?

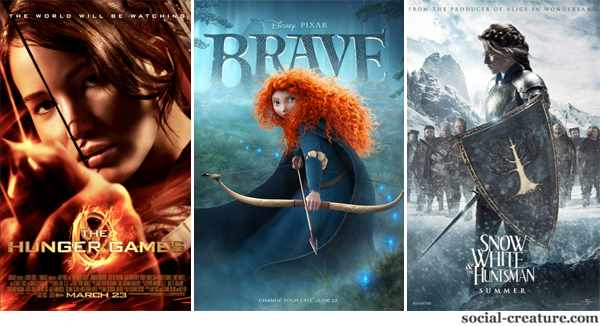

Considering the cruel, dystopian premise of The Hunger Games, Katniss will likely get to have as fun as an overachiever prepping for the SATs. And while Kristen Stewart as persecuted maiden turned, apparently, warrior in Snow White and the Huntsman (whose producer previously suited up Alice for battle in Wonderland) couldn’t possibly be more joyless and blank than as Bella (….right??), my money’s on Brave‘s Merida to win in the the flat out cool department, here:

Either way, while Tony Stark is an archetype boys grow into, the above are all manifestations of one girls grow out of, and when they do, they will expect their own spirit superheroine to aspire to. Someone who doesn’t have to be brutalized to be a badass, or a predator to be a hero. Someone clever and charming and cool as fuck, whom you’d just as soon want to party with as have saving the world; who’s faced the dark forces that don’t understand her and threaten to break her and strip her of her dignity, and, like the century of superheroes before her, has overcome. The next 21st century superhero will be a chick. The girls coming for the 21st century won’t be satisfied with anything less.