A month before the premiere of True Blood’s third season earlier this summer I wrote a post about the first 21st century superhero. The new Iron Man, as reimagined by Jon Favreau and portrayed by Robert Downey Jr., had broken the mold constricting the superhero archetype since its inception back in the late 1930’s, and in its place offered a vibrantly modern model for the character, reflecting the unique culture, ethos, and mores of the 21st century. True Blood, I’m realizing, is now doing the same for that other undying superhuman trope: the vampire.

Of course, the vampire has been undead for a lot longer. The earliest recorded vampire myth dates back to Babylonia, about 4,000 years ago, and over the millennia it has appeared in almost every culture. But lets cut to the chase: 1922 was year vampires broke ground in film (though, technically, they’d made a few cameos before then). It was the year F. W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu” came out.

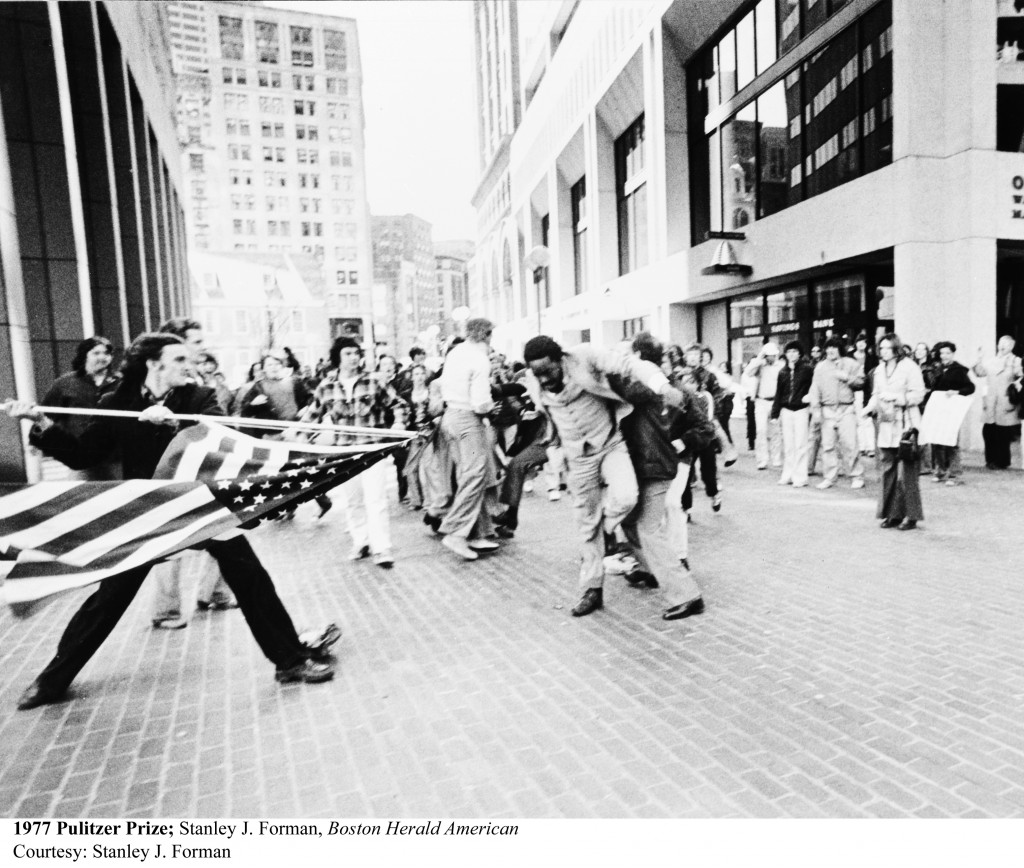

Take a good look. That’s what a movie vampire used to be. A creature no teen girl, or anyone else for that matter, would want to see as a lead in a summer mystical romance franchise. In all the silent films that featured vampires there was always a clear and consistent view: here be monsters.

While this original archetype might have undergone a radical transformation over the past 80+ years of cinema — from grotesque monster to, ironically, heartthrob, a result of the only evolutionary force vampires are actually subject to: sexual selection, naturally — don’t be fooled. Just because Twilight’s Edward Cullen or the whatever-their-names-are characters of The Vampire Diaries happen to be getting panties in a twist at the moment, they are not in any way contemporary. Much has been made about the exceptionally “old-fashioned” gender roles in Twilight, but that analysis is basically missing the forest for one tree. Think about it: is there ANYTHING that happens in Twilight that could not have happened just as easily 50 years ago? You could turn Twilight into a 1950’s period piece and basically NOTHING about the major plot points, dialogue, personalities, relationships, or motivations — of either the vampires OR humans in this saga — would need to change. This does not a 21st century story make. In fact, if you’re curious about exactly why Twilight is so popular, the mechanics of this process are actually quite timeless:

Twilight’s preternatural hotties aren’t so much throwbacks as they are completely out of time. The story could be happening in any age; its characters’ capacity to reflect some kind of cultural context is irrelevant, probably detrimental.

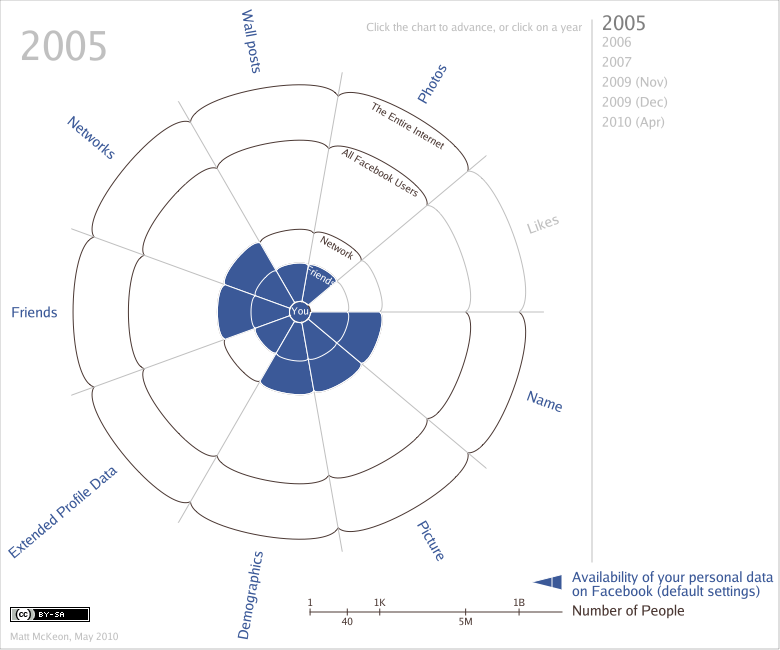

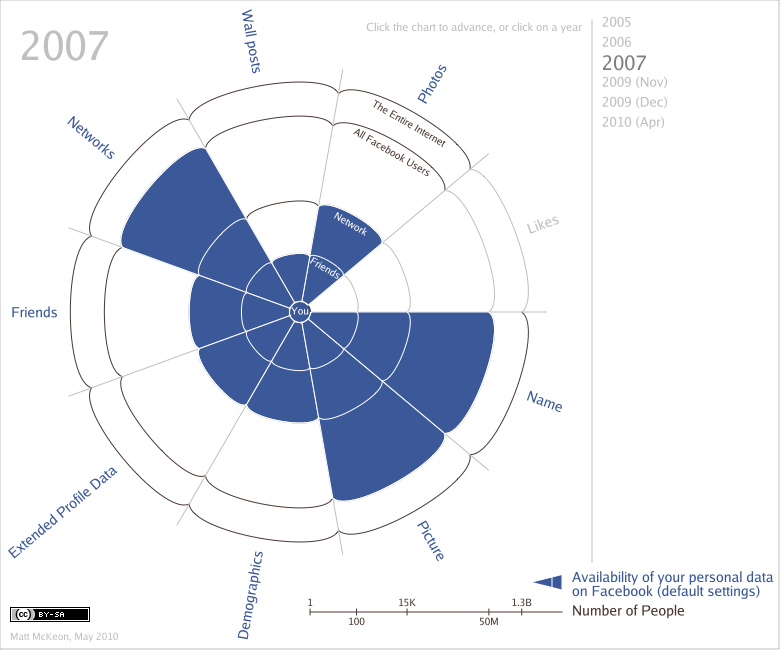

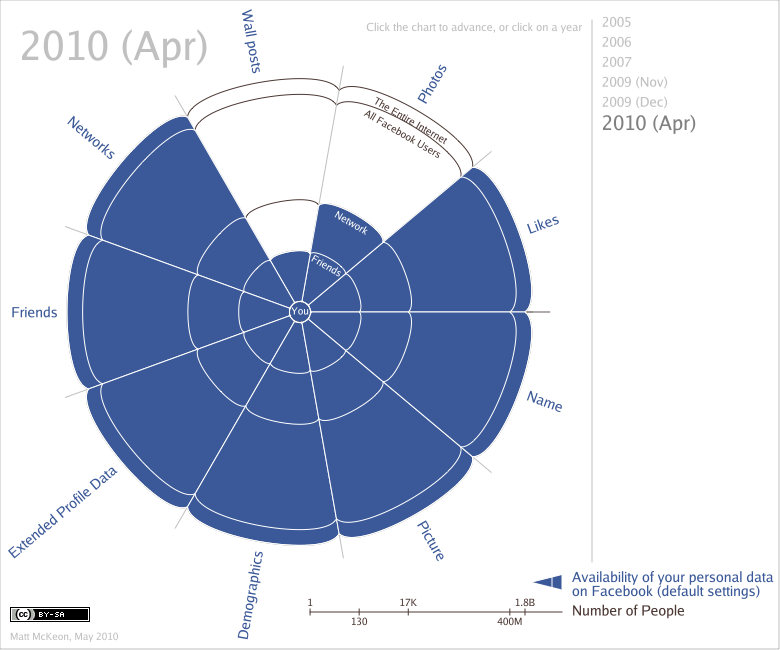

The predominant Millennial quality that grounds Iron Man in the 21st century, I wrote, is transparency. In his total openness about everything from his deepest secret to his fleeting impulses he is as “post-privacy” as Facebook would have us all become. To suggest that True Blood’s vampires are uniquely modern because they too, like Tony Stark, have revealed their secret identity to the world, would be easy — it is, after all the premise that the entire show is based on — but it wouldn’t be accurate. For Stark, radical transparency is a way of life. You never have to wonder what Tony Stark is thinking because it’s usually exactly what’s coming out of his mouth at any given moment. The vampires on true blood are anything but transparent. Their secret truths and ulterior motives are consistently obscure. Tellingly, even Sookie Stackhouse, the show’s mind-reader, can’t penetrate their thoughts. Despite a superficial simulation, transparency is not really a quality that connects True Blood’s vampires to the modern age. But you know what does?

Recycling.

These vampires are environmentally conscious! Hey, it’s the the 21st century, caring about the environment is hot! In fact, in the wake of the BP Oil Spill disaster which has affected all the Gulf states — chief among them, Louisiana, True Blood’s setting — there is a subtly startling undercurrent of environmentalism running through this season’s sublot. At one point, Russell Edgington, the 3,000-year old vampire King of Mississippi, a new character introduced this season, rhapsodizes, “I mean, do you remember how the air used to smell? How humans used to smell? How they used to taste?” Earlier, the vampire Queen of Louisiana describes a rare delicacy: “A Latvian boy. Has to be tasted to be believed. Not polluted like most humans. Tastes exactly the way they used to taste before the industrial revolution fucked everything to hell.” When Russell asks rhetorically, “What other creature actively destroys its own habitat,” one imagines these vampires didn’t need to see an Inconvenient Truth because they’ve lived it. They may be blood-sucking fiends but destroying the planet is below even their standards.

Nevertheless, consumer culture that they’ve lived to find themselves in, they’re not beyond shopping at the mall. (Looking good is, after all, a vampire priority.)

No doubt, there’ll be some anecdote about a vampire shopping online eventually. Most likely Eric will get there before Bill, I’m assuming, based on this classic exchange from season 1:

Eric: “I sent you three texts, why didn’t you reply?”

Bill: “I hate using the number keys to type.”

In fact, while Bill might be True Blood’s most conservative vampire (how postmodern!) — his education on how to be a vampire for the 17-year old girl he’s just been forced to turn into one is about as awkward and evasive as the birds and the bees talk from a religious dad — Eric is, arguably, its most progressive. That is, he has no fear of progress. Eric might be 1,000 years old but he’s as naturally at ease with his tech gadgets as any “digital native.” So far, he’s the only vampire I’ve seen use a bluetooth device. Ever.

As the proprietor of a popular vampire bar called Fangtasia, Eric clearly recognized “The Great Revelation” — as the vampires call their coming out to the world — as a great business opportunity. Entrepreneurship is an unexpected quality for a vampire in general — I mean, why bother with such pedestrian concerns when you’re immortal, right? On the other hand, what else would you do with an eternity of nights? Might as well launch a nightlife startup. According the Wall Street Journal, The Great Recession, which began in full force around the time True Blood first got on the air, is churning out ever more entrepreneurs. Entrepreneur.com reports, 8.7% of job seekers gained employment by starting their own businesses in the second quarter of 2009, and they expect to see even more people starting their own businesses in 2010. So it’s no surprise that 21st century vampires would be business-minded. Upon visiting Fangtasia, Russell, himself a semi-silent owner of a werewolf bar in Mississippi called Lou Pines, even tells Eric, “We must talk of franchising.”

If being an entrepreneur isn’t your thing, there’s always the royal route: seizing assets from your subjects. In the vampire Queen’s case, that asset is vampire blood, which she then has other vampires move as black market narcotic. Since selling their blood is a high crime among vampires, it’s initially unclear why the Queen would be doing this. What inscrutable and ominous vampiric motives could she have? By season 3 it’s revealed that the Queen needs the money to pay off the IRS. For vampires in the 21st century, death might not be certain, but taxes are. Indeed, True Blood’s portrayal of vampire culture is more of a bureaucracy than any other cinematic depiction. After a religious fanatic suicide bomber self-detonates at a party in a vampire lair, killing a number of humans and vampires in attendance, there are, literally, forms that the lair’s owner has to fill out in this situation — a sequence that encapsulates the equally bizarre extremes of both the terrorism and banality of our age.

While just last Wednesday, U.S. District Judge Vaughn Walker ruled that California’s Proposition 8 initiative, which denies marriage rights to same-sex couples, was unconstitutional, on True Blood, same-sex couple Russell and Talbot have been married for 700 years. Homoerotica is by no means anything new in vampire lore, but gay marriage?? There’s a concept that barely existed in the public discourse before the 21st century. And Russell and Talbot’s relationship is exactly what you’d expect from a couple that’s been married for 7 centuries — anything but erotic. A particularly noticeable departure for the otherwise seriously agrosexual HBO series. Of course, the new phenomenon of marriage between vampire and human — which, though legal in the word of True Blood, is still highly controversial — has, from the show’s beginnings, served as a running metaphor for “marriage equality.” Alan Ball, the creator of True Blood, as well as Six Feet Under, and the Oscar-winning screenwriter of American Beauty, is not only someone who clearly understands a thing or two about the modern existential condition, he is also an openly gay man. No surprise, then that True Blood’s very opening credits sequence weekly drives home a starkly unfantastical image that connects vampires to that other minority fighting religious opposition for equal rights in the 21st century.

“Alternative lifestyle,” an often-used euphemism for homosexuality, is actually a perfect way to describe True Blood’s approach to vampirism. Even the show’s brilliantly integrated marketing campaigns have sought to bring True Blood’s fictional world off the screen and into reality by treating vampires as an increasingly visible minority with their own lifestyle brands and targeted advertising:

True Blood’s vampires even blog. Well, technically, it’s only Jessica, with her http://babyvamp-jessica.com blog, but as a 17 year-old who just became undead last year she’s the only Gen-Y vampire on the show, so obviously she’d be the one blogging — check out the awesomely pointless first few entries — 1, 2, 3 — this directionless experimentation with a new “toy” is exactly how a teenager would start a blog. (Vampire diaries?? Who the hell keeps a “diary” anymore in the age of social media? Sheesh.)

Overall, there is a deep, underlying theme about progress coursing through True Blood. “It’s vampires like you, who’ve been holding the rest of us back for centuries,” sneers Russell before destroying a Spanish Inquisition-era vampire Magister. It’s the vampires that are most hung up on the past who are some of the show’s craziest messes. The psychotic vampire Queen, who’s stuck in some perpetual 1940’s costume drama, has just been stripped of power; Lorena, whose inability to get over her past with Bill becomes her destruction; Eric’s newly-revealed 1,000 year old revenge obsession for the murder of his father will no doubt promptly lead him into some kind of trouble this season. Godric, Eric’s maker, even destroyed himself in part because after 2,000 years he could no longer bear that vampires had not progressed; that he hadn’t. Unlike the atemporal caricatures of the other franchises, True Blood’s vampires offer a uniquely compelling commentary on our rapidly changing present through their own, archly extrahuman, relationship to it. We are living in a time when change, whether we like it or not, is coming at us so fast and furious we can barely comprehend it — speaking on a panel at Techonomy last week, Google CEO Eric Schmidt said we now create 5 exabytes of data every two days, an amount equal to all the information created from the dawn of civilization through 2003. Who can really understand whatever the hell that even means? True Blood’s vampires are at once representations of cultural change within the narrative of the show, and, likewise, must themselves confront a new millennium’s progress. Some adapt better than others. Some have more sinister interpretations of where progress should lead, but they, like the rest of us in the 21st century, either accept change, or deny it at their own peril.