Algorithms are the perfect tool for delivering individualized exploitation to billions. They may yet have potential for mobilizing collective power at scale.

Buy Me a Sandwich

Out in California, my friend is working on a new kind of energy storage startup. Here’s what they do. They buy electricity from the grid when it’s cheap (middle of the night), and store it in a battery in your house for you to use during the day, when demand is high. Participants will be able to save 20%-30% on their energy bills. And the best part is you don’t even have to do anything. The whole thing runs on algorithms.

I was thinking about this as I read Ben Tarnoff’s article in The Guardian, which begins:

What if a cold drink cost more on a hot day?

Customers in the UK will soon find out. Recent reports suggest that three of the country’s largest supermarket chains are rolling out surge pricing in select stores. This means that prices will rise and fall over the course of the day in response to demand. Buying lunch at lunchtime will be like ordering an Uber at rush hour.

But what if an algorithm bought it for you at midnight instead?

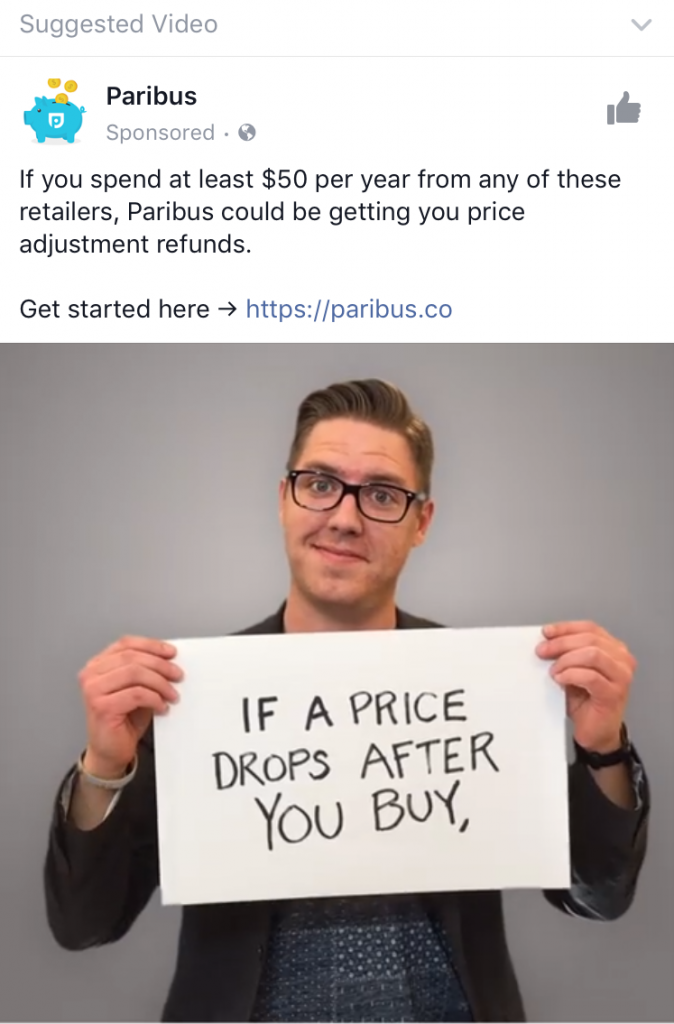

Amid the infinite churn of natural and political terrors— juxtaposed with photos of babies made by people I love — blowing up my Facebook feed, I keep seeing a hipster hostage video selling me something called Paribus.

“Stores change their prices all the time — and many of them have price guarantees,” explains Paribus’ App Store description. “Paribus gets you money when prices drop. So if you buy something online from one of these retailers and it goes on sale later, Paribus automatically works to get you the price adjustment.”

Most likely the reason Facebook expects I’d be interested in this service (more on this later) is because I already have an app duking it out with Comcast to lower my bill.

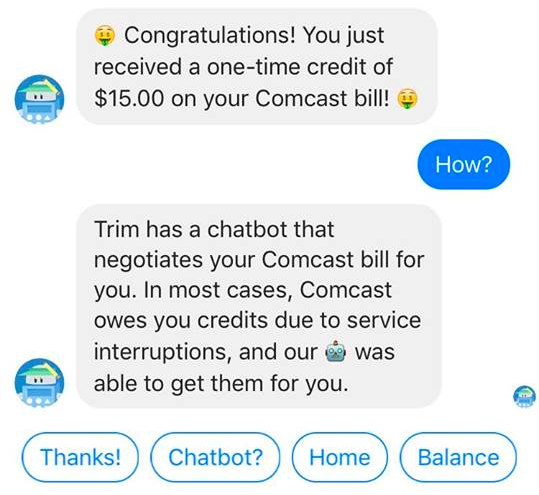

It sends me updates via Facebook Messenger to let me know its progress:

And I message it back choose-your-own-adveture style responses:

This feature is part of a service called Trim, which positions itself as “a personal assistant that saves money for you.” (It makes money by taking a cut of the recovered charges.)

Trim calls its Comcast negotiator bot, knowingly:

And, indeed — we should all be thinking about the possibilities for algorithm defense.

Buy Me A Monopoly

The day Amazon announced its purchase of Whole Foods, shares in both Kroger and Walmart — which generates more than half its revenue from grocery sales — went into free-fall. Kroger’s in particular fell 8% in a matter of hours.

On the day the sale closed, Whole Foods’ new management cut prices by up to 43%.

“Amazon has demonstrated that it is willing to invest to dominate the categories that it decides to compete in,” said Mark Baum, a senior vice president at the Food Marketing Institute. But the way Amazon “decides to compete” is to actually make the category uncompetitive, driving other players out until it has become the category.

Previously on Amazon: book stores.

Tarnoff writes:

Amazon isn’t abandoning online retail for brick-and-mortar. Rather, it’s planning to fuse the two. It’s going to digitize our daily lives in ways that make surge-pricing your groceries look primitive by comparison. It’s going to expand Silicon Valley’s surveillance-based business model into physical space, and make money from monitoring everything we do.

Concepts like Paribus, or Trim’s “Comcast Defense” are still primitive now, too, but extrapolate the possibilities out at scale. Imagine hundreds of thousands of people on a negotiation platform like this. That becomes the ability to exert real power. To pit Comcast and Verizon and AT&T against each other for who will offer the best deal, and have the leverage to switch all your members over en masse.

Reading Trim’s about page, it seems possible the thought could have crossed their minds:

So far, we’ve saved our users millions of dollars by automating little pieces of their day-to-day finances.

Now we’re starting to work on the hard stuff. Will I have enough money to retire someday? Which credit card should I get? Can my car insurance switch automatically to a cheaper provider?

Maybe Trim’s already thinking of the power of collective negotiating. Or maybe someone else will. The idea isn’t even all that new. It’s essentially how group insurance plans work. And unions. We’ve come up with it before. But we’ve never really tried it with code.

Buy Me A Pen

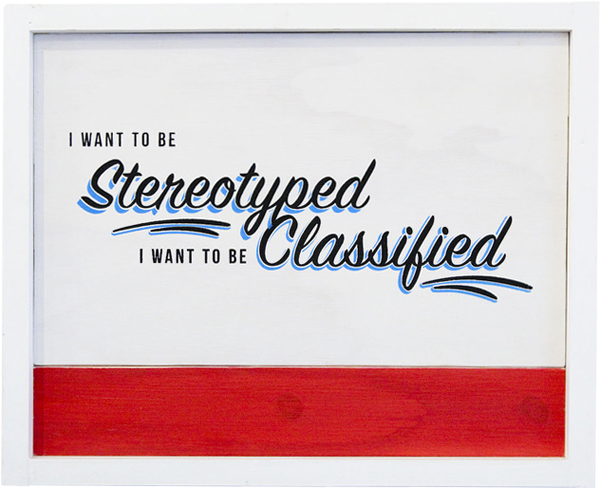

art by Curtis Mead

“When mass culture breaks apart,” Chris Anderson wrote a decade ago, in The Long Tail, “It doesn’t re-form into a different mass. Instead it turns into millions of microcultures, which coexist and interact in a baffling array of ways.”

On this new landscape of “massively parallel culture,” as Anderson called it, hyper-segmentation has become our manifest destiny.

Now we atomize the universal, dividing into ever nicher niches. We invent new market subsegments where none previously existed, or need to. We splash pink onto pens to create “differentiated” product lines:

Why?

Because segmentation sells.

Those pink pens “For Her”? They cost up to 70% more than Bic’s otherwise identical ones for everyone.

And the algorithms got this memo: there’s incentive to create ever more segmented “filter bubbles.”

It’s lucrative. And effective.

As John Lanchester writes in the London Review of Books:

Facebook knows your phone ID and can add it to your Facebook ID. It puts that together with the rest of your online activity: not just every site you’ve ever visited, but every click you’ve ever made. Facebook sees you, everywhere. Now, thanks to its partnerships with the old-school credit firms, Facebook knew who everybody was, where they lived, and everything they’d ever bought with plastic in a real-world offline shop. All this information is used for a purpose which is, in the final analysis, profoundly bathetic. It is to sell you things via online ads.

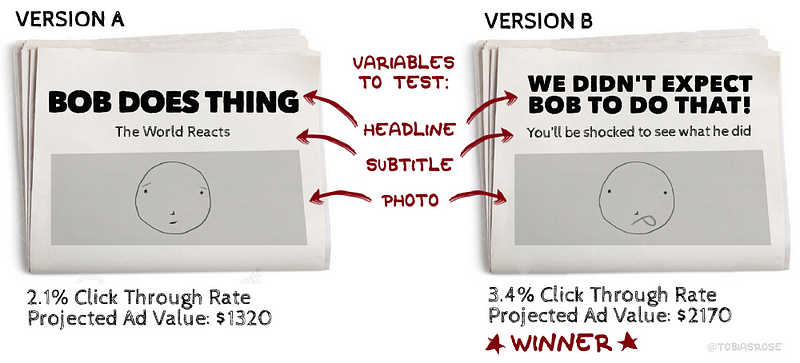

Buy Me Clicks

All day long, Facebook’s News Feed algorithm “is mapping your brain, seeking patterns of engagement,” writes Tobias Rose. “It can predict what you’ll click on better than anyone you know. It shows you stories, tracks your responses, and filters out the ones that you are least likely to respond to. It follows the videos you watch, the photos you hover over, and every link you click on.”

And Facebook follows you even when you’re not on Facebook. “Because every website you’ve ever visited (more or less) has planted a cookie on your web browser,” writes Lanchester, “when you go to a new site, there is a real-time auction, in millionths of a second, to decide what your eyeballs are worth and what ads should be served to them, based on what your interests, and income level and whatnot, are known to be.”

Facebook’s algorithms can create not only a private, personal pipeline of media, but an entirely individualized reality where information is repackaged for you — like pink pens — dynamically, in real-time, to whatever color, shape, or price point will extract the most value out of you specifically.

Four researchers based in Spain creat[ed] automated [shopper] personas to behave as if, in one case, ‘budget conscious’ and in another ‘affluent’, and then checking to see if their different behaviour led to different prices. It did: a search for headphones returned a set of results which were on average four times more expensive for the affluent persona. An airline-ticket discount site charged higher fares to the affluent consumer. In general, the location of the searcher caused prices to vary by as much as 166 per cent.

An anti-Clinton ad repeating a notorious speech she made in 1996 on the subject of ‘super-predators’… was sent to African-American voters in areas where the Republicans were trying, successfully as it turned out, to suppress the Democrat vote. Nobody else saw the ads.

“As consumers,” Tarnoff writes, “we’re nearly powerless, but as citizens, we can demand more democratic control of our data. The only solution is political.”

I’ve had the same thought. In an article last year about how technology has gotten so good at degrading us even some of its creators are starting to have enough, I wrote, “We take it for granted now, that cars have seat-belts to keep the squishy humans inside from flying through a meat-grinder of glass and metal during a collision. But they didn’t always. How did we ever get so clever? Regulation.”

And I still believe it. But we must also realize: we find ourselves now in a climate of hostility toward consumer and citizen protection. (Has anyone heard from the EPA lately?) And the breakneck speed with which technology is charging exponentially ahead of borders’ or regulation’s ability to keep pace isn’t about to relent. Hell, even the Council on Foreign Relations is out here like, “Democratic governments concerned about new digital threats need to find better algorithms to defend democratic values in the global digital ecosystem.”

Oof.

One way or another, when it comes to defense from algorithmic forces being deployed against us… we’re gonna need a bigger bots.

Putin says the nation that leads in AI ‘will be the ruler of the world’ https://t.co/npT6ilfx4C pic.twitter.com/keiKuzxasm

— The Verge (@verge) September 4, 2017

Buy Me Power

We’ve been classified and stereotyped and divided and conquered by algorithms. Lines of code deliver custom-targeted exploitation to billions of earthlings at once.

Can our individual fragments of power be scaled towards something bigger by them as well?

“Addressing our biggest issues as a species — from climate change, to pandemics, to poverty —” (to Jesus Christ, have you tried ever canceling your Comcast account?) “— requires us to have a common narrative of the honest problems we face,” writes Rose. “Without this, we are undermining our greatest strength — our unique ability to cooperate and share the careful and important burdens of being human.”

As individuals we are indeed basically powerless, and algorithms have proven a stunningly effective tool for extracting ever greater value out of our atomization. We have perhaps yet to imagine the potential of what algorithms deployed to concentrate our individual power into a group force can achieve at a global scale.

One thing is for certain — we ned to start thinking about defense.

Oh, and if you’re a homeowner in California (or have a cool landlord) and want to lower your energy bill (and “inadvertently” accelerate the adoption of renewables to the grid), go sign up to be a beta tester for my friend’s energy startup! They’ll install a battery for free at your home to reduce your electric bill if you let them train their algorithms to predict when you’re going to need power.