According to the Mayan calendar — as translated by new-age hippies I used to know, and depicted by Roland Emmerich — the year 2012 is alleged to herald the apocalypse. Perhaps this collective unconscious sense of mass destruction is what’s driving the popularity of turn-of-the-millennium musings about the end of the world. In June 2008, Adbusters’ cover story was, literally, titled, “Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization.” Three and a half years later, Vanity Fair’s first issue of 2012 asks, “You Say You Want a Devolution? From Fashion to Housewares, Are We in a Decades-Long Design Rut?” While these two publications could arguably not be further apart on the target audience spectrum, they’re singing the same doomsday tune. As Kurt Andersen writes in the Vanity Fair piece, “The past is a foreign country, but the recent past—the 00s, the 90s, even a lot of the 80s—looks almost identical to the present.” The last line of the article concludes, “I worry some days, this is the way that Western civilization declines, not with a bang but with a long, nostalgic whimper.” But has cultural evolution really come to a grinding halt in the 21st century, or are we simply looking in all the old places, not realizing it’s moved on?

In Adbusters, Douglas Haddow sets up the alleged apocalypse like so:

Ever since the Allies bombed the Axis into submission, Western civilization has had a succession of counter-culture movements that have energetically challenged the status quo. Each successive decade of the post-war era has seen it smash social standards, riot and fight to revolutionize every aspect of music, art, government and civil society. But after punk was plasticized and hip hop lost its impetus for social change, all of the formerly dominant streams of “counter-culture” have merged together. Now, one mutating, trans-Atlantic melting pot of styles, tastes and behavior has come to define the generally indefinable idea of the ‘Hipster.’

Echoing that sentiment in Vanity Fair, Andersen writes:

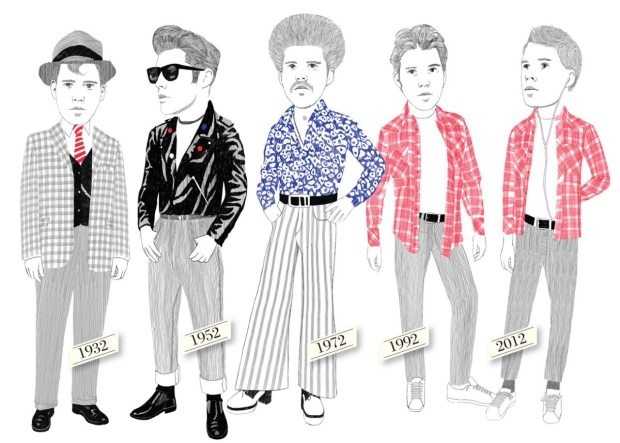

Think about it. Picture it. Rewind any other 20-year chunk of 20th-century time. There’s no chance you would mistake a photograph or movie of Americans or an American city from 1972—giant sideburns, collars, and bell-bottoms, leisure suits and cigarettes, AMC Javelins and Matadors and Gremlins alongside Dodge Demons, Swingers, Plymouth Dusters, and Scamps—with images from 1992. Time-travel back another 20 years, before rock ’n’ roll and the Pill and Vietnam, when both sexes wore hats and cars were big and bulbous with late-moderne fenders and fins—again, unmistakably different, 1952 from 1972. You can keep doing it and see that the characteristic surfaces and sounds of each historical moment are absolutely distinct from those of 20 years earlier or later: the clothes, the hair, the cars, the advertising—all of it. It’s even true of the 19th century: practically no respectable American man wore a beard before the 1850s, for instance, but beards were almost obligatory in the 1870s, and then disappeared again by 1900.

Writing about the Adbusters piece in 2008, I pointed to a central flaw in the premise: the emergence of what Chris Anderson, in his 2006 book of the same name, calls, The Long Tail. Digital technology, Anderson writes, has ushered in “An evolution from an ‘Or’ era of hits or niches (mainstream culture vs. subcultures) to an ‘AND’ era.” In this new, rebalanced equation, “Mass culture will not fall, it will simply get less mass. And niche culture will get less obscure.” What Adbusters saw as the end of Western civilization was actually the end of mass culture; a transition to a confederacy of niches. So, if mass culture, as the construct we, and Adbusters, had known it to be was over, what was there to be “counter” to anymore? (While, more recently, Occupy Wall Street has thrown its hat into the ring, it’s not so much anti-mass culture as it is pro-redefining the concept: the 99%, through the movement’s message — let alone mathematics — is not the counterculture. It IS the culture.)

Unlike Haddow, Andersen doesn’t blame the purported cultural stagnation on any one group of perpetrators. Rather, the “decades-long design rut” has descended upon us all, he suggests, like an aesthetic recession, the result of some unregulated force originating in the 1960′s and depreciating steadily until it simply collapsed, and none of us noticed until it was too late. “Look at people on the street and in malls,” Andersen writes, “Jeans and sneakers remain the standard uniform for all ages, as they were in 2002, 1992, and 1982. Since 1992, as the technological miracles and wonders have propagated and the political economy has transformed, the world has become radically and profoundly new.” And yet, “during these same 20 years, the appearance of the world (computers, TVs, telephones, and music players aside) has changed hardly at all, less than it did during any 20-year period for at least a century. This is the First Great Paradox of Contemporary Cultural History.”

Or is it?

In a 2003 New York Times article titled, The Guts of a new Machine, the design prophet of the 21st century revealed his philosophy on the subject: “People think it’s this veneer,” said the late Steve Jobs, “That the designers are handed this box and told, ‘Make it look good!’ That’s not what we think design is. It’s not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.”

Think about it. Picture it. Those big, bulbous cars Andersen describes, with their late-moderne fenders and fins, so unmistakably different from 1952 to 1977, just how different were they, really, in how they worked? Not that much. In the 20th century you could pop open the hood of a car and with some modicum of mechanics know what it was you were looking at. Now, the guy in the wifebeater working on the Camaro in his garage is an anachronism. You’ll never see that guy leaning over the guts of a post-Transformers, 2012 Camaro. Let alone a hybrid or an electric vehicle. “With rare exceptions,” Andersen argues, “cars from the early 90s (and even the late 80s) don’t seem dated.” And yet, there’s no way anyone would confuse a Chevy Volt with anything GM was making 10 years ago, or a Toyota Prius with what was on the road in the early 90s, or voice recognition capability, completely common in a 2012 model, as anything but a science fiction conceit in a show starring David Hasselhoff, in 80s. While it’s debatable that exterior automotive styling hasn’t changed in the past 30 years (remember the Tercel? The station wagon? The Hummer? A time before the SUV?) it’s indisputable that the way a 2012 automobile works has changed.

For the majority of human history the style shifts between eras were pretty much entirely cosmetic. From the Greeks to the Romans, from the Elizabethans to the Victorians, what fluctuated most was the exterior. It wasn’t until the pace of technological innovation began to accelerate in the 20th century that design became concerned with what lay beneath the surface. In the 1930s, industrial designer Raymond Loewy forged a new design concept, called Streamlining. One of the first and most widespread design concepts to draw its rationale from technology, Streamlining was characterized by stripping Art Deco, its flamboyant 1920’s predecessor, of all nonessential ornamentation in favor a smooth, pure-line concept of motion and speed. Under the austerity of the Depression era, the superficial flourishes of Art Deco became fraudulent, falsely modern. Loewy’s vision of a modern world was minimalist, frictionless, developed from aerodynamics and other scientific concepts. By the 1960’s Loewy’s streamlined designs for thousands of consumer goods — everything from toasters and refrigerators to automobiles and spacecrafts — had radically changed the look of American life.

What began in the 20th century as a design concept has, in the 21st, become THE design concept. Technological innovation — the impact of which Andersen breezes past — has become the driving force behind aesthetic innovation. Design is how it works. Aerodynamics has paved the way for modern considerations like efficiency, performance, usability, sustainability, and more. But unlike fluctuating trends in men’s facial hair or collar size, technology moves in one direction. It does not vacillate, it iterates, improving on what came before, building incrementally. The biggest aesthetic distinctions, therefore, have become increasingly smaller.

Consider, for example, this optical illusion:

What, exactly, is the difference between the two things above? Rewind twenty years, and it’s already unlikely most people would have been able to really tell a difference in any meaningful way. Go back even further in time, and these things become pretty much identical to everyone. Yet we, the inhabitants of 2012, would never, ever, mistake one for the other. The most minute, subtlest of details are huge universes of difference to us now. We have become obsessives, no longer just consumers but connoisseurs, fanatics with post-industrial palates altered by exposure to a higher resolution. And it’s not just about circuitry. In fashion, too, significant signifiers have become more subtle.

The New York Magazine writeup for Blue in Green, a Soho-based men’s lifestyle store reads:

Fifteen hard-to-find, premium brands of jeans—most based in Japan, a country known for its quality denim—line the walls. Prices range from the low three figures all the way up to four figures for a pair by Kyuten, embedded with ground pearl and strips of rare vintage kimono. Warehouse’s Duckdigger jeans are sandblasted in Japan with grains shipped from Nevada and finished with mismatched vintage hardware and twenties-style suspender buttons. Most jeans are raw, so clients can produce their own fade, and the few that are pre-distressed are never airbrushed; free hemming is available in-house on a rare Union Special chain-stitcher from an original Levi’s factory.

(Sidenote: it’s not just jeans. Wool — probably not the next textile in line on the cool spectrum after denim — is catching up. Esquire apparently thinks wool is so interesting to their readers they created an illustrated slide show about different variations of sheep.)

“Our massively scaled-up new style industry naturally seeks stability and predictability,” Andersen argues. “Rapid and radical shifts in taste make it more expensive to do business and can even threaten the existence of an enterprise.” But in fact, when it comes to fashion, quite the opposite is true. To keep us buying new clothes — and we do: according to the Daily Mail, women have four times as many clothes in their wardrobe today as they did in 1980, buying, and discarding half their body weight in clothes per year — styles have to keep changing. Rapid and radical shifts in taste are the foundation of the fashion business; a phenomenon the industry exploits, not fears. And the churn rate has only accelerated. “Fast Fashion,” a term coined in the mid-2000′s, means more frequent replacement of cheaper clothes that become outdated more quickly.

“The modern sensibility has been defined by brief stylistic shelf lives,” Andersen writes, “Our minds trained to register the recent past as old-fashioned.” But what has truly become old-fashioned in the 21st century, whether we’ve realized it or not, is the idea of a style being able to define a decade at all. It’s as old-fashioned as a TV with a radial dial or retail limitations dictated by brick and mortar. As Andersen himself writes, “For the first time, anyone anywhere with any arcane cultural taste can now indulge it easily and fully online, clicking themselves deep into whatever curious little niche (punk bossa nova, Nigerian noir cinema, pre-war Hummel figurines) they wish.” And primarily what we wish for, as Andersen sees it, is what’s come before. “Now that we have instant universal access to every old image and recorded sound, the future has arrived and it’s all about dreaming of the past.” To be fair, there is a deep nostalgic undercurrent to our pop culture, but to look at the decentralization of cultural distribution and see only “a cover version of something we’ve seen or heard before” is to miss the bigger picture of our present, and our future. The long tail has dismantled the kind of aesthetic uniformity that could have once come to represent a decade’s singular style. In a confederacy of niches there is no longer a media source mass enough to define and disseminate a unified look or sound.

As with technology, cultural evolution in the 21st century is iterative. Incremental changes, particularly ones that originate beneath the surface, may not be as obvious through the flickering Kodak carousel frames of decades, but they are no less profound. In his 2003 book, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life, Richard Florida opens with a similar time travel scenario to Andersen’s:

Here’s a thought experiment. Take a typical man on the street from the year 1900 and drop him into the 1950s. Then take someone from the 1950s and move him Austin Powers-style into the present day. Who would experience the greater change?

On the basis of big, obvious technological changes alone, surely the 1900-to-1950s traveler would experience the greater shift, while the other might easily conclude that we’d spent the second half of the twentieth century doing little more than tweaking the great waves of the first half.

But the longer they stayed in their new homes, the more each time-traveler would become aware of subtler dimensions of change. Once the glare of technology had dimmed, each would begin to notice their respective society’s changed norms and values, and the ways in which everyday people live and work. And here the tables would be turned. In terms of adjusting to the social structures and the rhythms and patterns of daily life, our second time-traveler would be much more disoriented.

Someone from the early 1900s would find the social world of the 1950s remarkably similar to his own. If he worked in a factory, he might find much the same divisions of labor, the same hierarchical systems of control. If he worked in an office, he would be immersed in the same bureaucracy, the same climb up the corporate ladder. He would come to work at 8 or 9 each morning and leave promptly at 5, his life neatly segmented into compartments of home and work. He would wear a suit and tie. Most of his business associates would be white and male. Their values and office politics would hardly have changed. He would seldom see women in the work-place, except as secretaries, and almost never interact professionally with someone of another race. He would marry young, have children quickly thereafter, stay married to the same person and probably work for the same company for the rest of his life. He would join the clubs and civic groups befitting his socioeconomic class, observe the same social distinctions, and fully expect his children to do likewise. The tempo of his life would be structured by the values and norms of organizations. He would find himself living the life of the “company man” so aptly chronicled by writers from Sinclair Lewis and John Kenneth Galbraith to William Whyte and C.Wright Mills.

Our second time-traveler, however, would be quite unnerved by the dizzying social and cultural changes that had accumulated between the 1950s and today. At work he would find a new dress code, a new schedule, and new rules. He would see office workers dressed like folks relaxing on the weekend, in jeans and open-necked shirts, and be shocked to learn they occupy positions of authority. People at the office would seemingly come and go as they pleased. The younger ones might sport bizarre piercings and tattoos. Women and even nonwhites would be managers. Individuality and self-expression would be valued over conformity to organizational norms — and yet these people would seem strangely puritanical to this time-traveler. His ethnic jokes would fall embarrassingly flat. His smoking would get him banished to the parking lot, and his two-martini lunches would raise genuine concern. Attitudes and expressions he had never thought about would cause repeated offense. He would continually suffer the painful feeling of not knowing how to behave.

Out on the street, this time-traveler would see different ethnic groups in greater numbers than he ever could have imagined — Asian-, Indian-, and Latin-Americans and others — all mingling in ways he found strange and perhaps inappropriate. There would be mixed-race couples, and same-sex couples carrying the upbeat-sounding moniker “gay.” While some of these people would be acting in familiar ways — a woman shopping while pushing a stroller, an office worker having lunch at a counter — others, such as grown men clad in form-fitting gear whizzing by on high-tech bicycles, or women on strange new roller skates with their torsos covered only by “brassieres” — would appear to be engaged in alien activities.

People would seem to be always working and yet never working when they were supposed to. They would strike him as lazy and yet obsessed with exercise. They would seem career-conscious yet fickle — doesn’t anybody stay with the company more than three years? — and caring yet antisocial: What happened to the ladies’ clubs, Moose Lodges and bowling leagues? While the physical surroundings would be relatively familiar, the feel of the place would be bewilderingly different.

Thus, although the first time-traveler had to adjust to some drastic technological changes, it is the second who experiences the deeper, more pervasive transformation. It is the second who has been thrust into a time when lifestyles and worldviews are most assuredly changing — a time when the old order has broken down, when flux and uncertainty themselves seem to be part of the everyday norm.

It’s the end of the world as we’ve known it. And I feel fine.