Once you ‘got’ Pop, you could never see a sign again the same way again. And once you thought Pop, you could never see America the same way again.

– Andy Warhol

It is totally disconcerting to discover a book that pretty much compiles your insights and articulates them back to you. Buying In: The Secret Dialogue Between What We Buy & Who We Are, by Rob Walker, delves into many of the exact same observations as I have witnessed amid the ecosystem of contemporary culture, marketing, and identity. Reading it feels something like discovering America’s Next Top Model is biting your personal fashion style, I would imagine. Sure, it’s incredibly validating to see your own insights coming at you from a New York Times Magazine writer, but it’s sorta frustrating to have to know that they’re not just yours anymore.

In social science there is probably nothing as revelatory as a contradiction exposed. That the emperor is not wearing any clothes is much more stunning a revelation than any critique of the fashion aesthetic. And it’s contradictions that Walker is interested in:

There was one specific incident that finally made me reconsider what I thought I knew about consumers, marketers, and even myself. This was the news that Nike had bought Converse.

To me, Nike’s famous swoosh logo had long been the mark of the manipulated, a symbol for suckers who take its “Just Do It” bullying at face value. It’s long been, in my view, a brand for followers. On the other hand, the Converse Chuck Taylor All Star had been a mainstay sneaker for me since I was a teenager back in the 1980’s, and I stuck with it well into my thirties. Converse was the no-bullshit yin to Nike’s all-style-and-image yang. It’s what my outsider heroes from Joey Ramone to Kurt Combain wore. So I found the buyout disheartening…. but why, really, did I feel so strongly about a brand of sneaker–any brand of sneaker?

As a consumer behavior columnist, Walker had observed as “the steady march of progress that had been reshaping media and technology for years broke into a sprint, through the rapid rise of devices and innovations like TiVo, the iPod, increasingly sophisticated cell phones, YouTube, Facebook, and so on.” He notes that according to many marketing experts and consumer-culture observers, this new landscape had created a “New Consumer:”

A clever creature armed with all kinds of dazzling technology, from ad-blocking gizmos to alternative, grassroots media. This added up to what professional zeitgeist watchers–

–and i’d like to add, none too few self-congratulatory alternative cultures–

like to call “a paradigm shift.” “Consumers don’t march in lockstep anymore,” one celebrated trend master declared. “We are immune to advertising,” other experts announced. The mindless “mass market” had been shouldered aside by thinking individuals: “Consumers are fleeing the mainstream.” Somehow we had all become more or less impervious to marketing and brands and logos; we could see through commercial persuasion.

The trade, business and mainstream press–

–as well as no shortage of idealistic social media folks–

have seconded this judgement. Thanks to “the explosion in information available to shoppers,” The New Yorker argued, “brand loyalty is in fast decline,” and “the customer is king.” The Economist, too, pointed to super-informed shoppers who have acquired “unprecedented strength” in their dealings with commercial persuaders and approvingly quoted a famous ad executive announcing: “For the first time the consumer is boss.” Advertising Age soberly informed its readers that because of “the power of the public,” consumers have lately obtained “increasing sway … over any product’s success”–in fact, the consumer is in control.

The only problem with this was that it did not match up particularly well with the realities of the marketplace that I was writing about every week in The Times Magazine.

It’s one thing to conclude that the advertising business is evolving with the new media landscape. But these giddy claims go well beyond that….

Meanwhile the number of brand messages we are exposed to goes up, and so does the amount of trash we produce. And on a more personal level: Have you noticed any decrease in the number of times you buy something you were sure you would love, only to regret it later or simply forget about in the back of a closet? There you are, contemplating the limitless and ever shifting choices in what to drink, what to wear, what to drive, what to buy. It is literally impossible to try everything for yourself. Be honest: As you navigate this brand-soaked world, do you feel in control?

Sure, we tell pollsters and friends that we’re sick of being bombarded with advertising, we’re indifferent to silly logos, we’re fed up with rampant materialism. In reality, one of the most significant changes I’ve observed over the years that consumer behavior has been my primary beat is something that goes well beyond the long-standing human tendency to enjoy acquiring things.

The change is particularly noticeable among many of the younger people I’ve met. Frequently, these smart and creative young people were quite happy to inform me that, yes, they were immune to commercial persuasion–that they saw right through it, as the experts liked to say. Meanwhile, they were playing key, active roles in helping certain products and brands succeed.

They were in the vanguard of what looks an awful lot like an increasingly widespread consumer embrace of branded, commercial, culture. The modern relationship between consumer and consumed is defined not by rejection at all, but rather by frank complicity.

This goes against what we’d want to think of ourselves, and of individuality. We want to think that our highly-attuned “seeing through”ness, and our distinctive tastes have set us apart, granted us superiority over the tastelessness of lowly label whores. We want to think that expressing our identities, and asserting our belonging within a particular cultural community is unrelated to, and, in fact, an escape from brand-consciousness. We want to think we are–as 77% of the respondents in a formal poll mentioned by Walker considered themselves to be–far smarter and savvier than most consumers. Which is a mathematical impossibility.

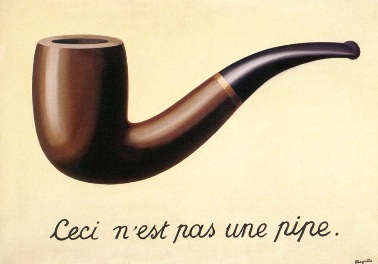

The truth of the matter is that actually we don’t really know ourselves that well at all. That’s the “Secret” in “The Secret Dialogue Between What We Buy and Who We Are.” We have come up with enough misconceptions about the relationship between, as Walker calls it, the consumer and the consumed, that the real mechanics of this interchange are happening beyond our consciousness. We’re not aware we’re naked beneath our fancy new clothes.

“Symbols matter to us,” Walker says:

Meaningful symbols (logos included) get created–and even when we claim to be immune from such things, we often participate in that meaning-creation ourselves….In the 21st century we still grapple with the eternal dilemma of wanting to feel like individuals and to feel as though we’re apart of something bigger than ourselves–and that, most of all we all seek ways to resolve this fundamental tension of modern life.

In Nation of Rebels: Why Counterculture Became Consumer Culture Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter delve into the social psychology history of individuality, excavating its modern beginnings from the wreckage of the post-WWII distrust of “mass culture.” They propose that witnessing how conformity had devastated Europe as enforced by the Nazis, plus the results of the Milgram experiment, which exposed some nasty realities about our human relationship to authority, “led conformity to become the new cardinal sin in our society.” By the time Walker gets around to weighing in on it, this manifest individualist destiny has become an American right.

Enter “The Pretty Good” problem, as Walker calls it. Or as Alex Bogusky says: “All products are excellent.” It’s no longer about what’s better than what, or what’s more reliable, or what’s more effective. It all works, it’s all really good. The way you choose between all this totally dependable functioning stuff is, essentially, based on what expresses you.

“Buying a $5,000 handbag just because it’s a status symbol is a sign of weakness,” Walker quotes a particular “keen observer of branded culture”: Miuccia Prada. “Presumably” Walker suggests, “buying a $5,000 Prada bag is okay, if you’re doing it for the right reasons–quality for instance.” But I don’t see anything ironic in Prada’s remark. It’s probably the way anorexics think about the eating habits of the obese. In between those extremes though, weakness or not, we all have to eat. And we all feel we have to express ourselves, define ourselves, locate ourselves, even, on the cultural spectrum. How do we do that in our modern world?

Well, like, take the gutterpunk bike messenger dude Walker comes across while investigating the resurgence of Pabst Blue Ribbon’s popularity, getting a PBR logo brand–that’s skin brand–the size of his back. This may seem a bit excessive, but “Pabst is part of my subculture,” he says. More specifically, it can function as a symbol of a subculture, and skin branding as a means of expressing both a personal commitment and community loyalty is actually not at all uncommon among fraternities. In the absence of a Greek letter, endorsing a brand–that’s logo brand–can, and often does, become adopted as a symbol of belonging to a culture or community. You might not have gotten a skin brand or bought a $5,000 handbag, but all of us have purchased things not just for our own “personal narrative,” as Walker suggest, but because they represented our culture, our context, where we belong.

This is actually the part in the book where Walker’s assessments start to fall apart, I think. Unlike his research on the consumer adoption of corporate brands, in chronicling “underground brands”–by which he means, essentially, lifestyle symbols developed by independent entrepreneurs–he doesn’t mention any research from talking directly to the adopters of these brands, and thus fails to convey that the adoption of both kinds of brands happens basically for the same reasons.

He gets part of it right. Many underground brand creators:

Clearly see what they are doing as not only non-corporate, but somehow anticorporate: making statements against the materlistic mainstream–but doing it with different forms of materialism.

Take a minute to get acclimated to the irony if you need to, but that’s not the real contradiction here. This is:

Perhaps the threat that brand-smart young people really pose to commercial persuaders is not that they have stopped buying symbols of rebellion. It is that they have figured out that they can sell those symbols, too.

What the exact definition of an “underground brand” is–beyond being created by “brand-smart young people”–is never actually defined, and that may be the root of the oversight. Walker’s case studies for underground brands are pretty much exclusively clothing, or even more precisely, t-shirt labels, but I’ve seen the same phenomenon play out with underground music brands bands, and events. A community, weather it’s mass or niche, Greek or gutterpunk, needs symbols, and the difference between how an “independent” maker of symbols behaves vs. a “corporate” one, is that the corporate one answers to Wall Street.

You can argue that size matters. That somewhere along the slippery slope a brand is either big or small, but I would imagine even small Wall Street-beholden brands would behave the same way big ones do. And conversely, as Walker himself talks about, though doesn’t quite process to it’s logical conclusion: to stay competitive, Wall-Street brands are starting to behave like indie ones. Scion’s success via alternative marketing, which Walker calls “murketing,” happened not because it invented its own grassroots community from scratch, but because it leveraged the communities around existing independent brands in much the same way a concert venue leverages the community around a music act.

Talking to independent brand creators, Walker says, “Made me realize that it wasn’t just commercial culture that the brand underground was co-opting–it was the most exclusive and elevated form of it.”

Which is kind of like saying that an indie-rock band “co-opts” Elton John. I think music fans are only too happy to have more options.

It’s not culture that’s being co-opted, it’s industry. An indie band “co-opts” the music industry, and indie brands “co-opt” the industry of commercial persuasion itself. This isn’t a “threat” to commercial persuasion, as Walker suggests, but an expansion, an upgrade. Commercial persuasion, v. 2.0.

Or whatever.

“It’s time to set aside the old conspicuous consumption argument that consumer behavior is all about status–all about badges,” Walker writes. “If the underground logo is a badge, it’s one that is most noteworthy for how few people can see it.”

Uh-huh…

The average underground logo–just like many corporate ones–may be more subdued than, say, the narcissistic in-your-face mania of Louis Vuitton’s logo, but the underground brand is a badge, and it’s one that is most notable for how meaningfully it expresses a community. (By the way, that requires visibility). It may not be all about “status” but it IS all about identity.

Suddenly, the book is not so disconcerting after all.