Don’t blame it on the algorithm — assuming you’re designing experiences for “happy, upbeat, good-life users” might make you a terrible person.

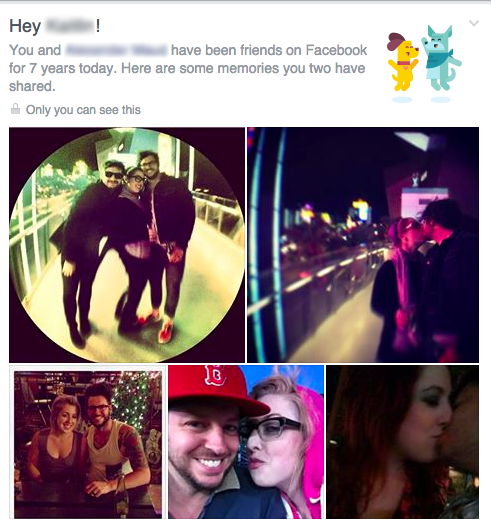

My friend is going through a divorce. Like nearly 5 million other Americans. And recently Facebook greeted her with this careless user experience:

When this UX intrusion happened to her, it reminded me of a similar, psychological violation I’d read about four months earlier. That post, by Eric Meyer, had begun:

I didn’t go looking for grief this afternoon, but it found me anyway, and I have designers and programmers to thank for it. In this case, the designers and programmers are somewhere at Facebook.

I know they’re probably pretty proud of the work that went into the “Year in Review” app they designed and developed, and deservedly so—a lot of people have used it to share the highlights of their years. Knowing what kind of year I’d had, though, I avoided making one of my own. I kept seeing them pop up in my feed, created by others, almost all of them with the default caption, “It’s been a great year! Thanks for being a part of it.” Which was, by itself, jarring enough, the idea that any year I was part of could be described as great.

Still, they were easy enough to pass over, and I did. Until today, when I got this in my feed, exhorting me to create one of my own. “Eric, here’s what your year looked like!”

A picture of my daughter, who is dead. Who died this year.

Yes, my year looked like that. True enough. My year looked like the now-absent face of my little girl. It was still unkind to remind me so forcefully.

I remember first reading this post the day it was published, Christmas eve 2014. When I went to look it up after my friend’s own violation by a Facebook app module I was surprised to (re)discover that it had been titled, generously, “Inadvertent algorithmic cruelty:”

And I know, of course, that this is not a deliberate assault. This inadvertent algorithmic cruelty is the result of code that works in the overwhelming majority of cases, reminding people of the awesomeness of their years, showing them selfies at a party or whale spouts from sailing boats or the marina outside their vacation house.

But for those of us who lived through the death of loved ones, or spent extended time in the hospital, or were hit by divorce or losing a job or any one of a hundred crises, we might not want another look at this past year.

To show me Rebecca’s face and say “Here’s what your year looked like!” is jarring. It feels wrong, and coming from an actual person, it would be wrong. Coming from code, it’s just unfortunate.

But of course, it did come from an actual person. “[The app] was awesome for a lot of people,” the product manager for Facebook’s Year in Review app, Jonathan Gheller, later told The Washington Post. Like all the digital experiences with, and within, which we all increasingly live our lives, an actual person — in fact a whole team of people — was responsible for concepting, designing, building, testing, and iterating this experience. No doubt, the responsibility for the rollout of this particular app featured prominently in a number of Facebook employees’ job performance reviews. From start to finish, this experience was crafted by people (not code). Calling its end result “inadvertent algorithmic cruelty” is like describing a drunk driving accident as “inadvertent gasoline cruelty.” For sure, it could have been avoided with an empty gas tank, but is that really the most accurate way to ascribe accountability in this situation? (Don’t blame it on the algohol).

“In creating this Year in Review app, there wasn’t enough thought given to cases like mine, or anyone who had a bad year,” Meyer wrote. “If I could fix one thing about our industry, just one thing, it would be that: to increase awareness of and consideration for the failure modes, the edge cases, the worst-case scenarios.”

If I could fix one thing about our industry, it would be to destroy the idea that these scenarios are edge cases.

Last year in the US, 2.6 million people died, leaving behind untold numbers of Facebook users who mourn the absence of their loved ones.

Right now 8.5 million people can’t find a job;

14.5 million people have cancer;

16 million people suffer from depression;

23.5 million people are addicted to alcohol and drugs;

45 million people live below the poverty line (including 16 million children)

These are not “edge cases.” These are not “worst case scenarios.” These are all people who use Facebook. And that’s not even counting your run of the mill disappointments, broken hearts, and inevitable wrongs and slights and meannesses that are, basically, life.

“The design [of the Year in Review app] is for the ideal user, the happy, upbeat, good-life user,” Meyer wrote. But if you are a product manager or UX designer creating experiences that will afflict affect hundreds of millions of people and you are only designing for an “ideal user”… at best that’s just lazy, and at worst — it’s creating LITERAL suffering.

As Oliver Burkeman writes in The Guardian:

The world, obviously, is a manifestly unjust place: people are always meeting fates they didn’t deserve, or not receiving rewards they did deserve for hard work or virtuous behaviour. Yet several decades of research have established that our need to believe otherwise runs deep.

Confronted with an atrocity they otherwise can’t explain, people become slightly more likely, on average, to believe that the victims must have brought it on themselves. Hence the finding, in a 2009 study, that Holocaust memorials can increase antisemitism. Or that reading about the eye-popping state of economic inequality could make you less likely to support politicians who want to do something about it. These are among numerous unsettling implications of the “just-world hypothesis”, a psychological bias explored in a new essay by Nicholas Hune-Brown at Hazlitt.

If we didn’t all believe that [things happen for a reason] to some degree, life would be an intolerably chaotic and terrifying nightmare in which effort and payback were utterly unrelated, and there was no point planning for the future, saving money for retirement or doing anything else in hope of eventual reward. We’d go mad.

Yet, ironically, this desire to believe that things happen for a reason leads to the kinds of positions that help entrench injustice instead of reducing it.

Much in the same way that the “just world” cognitive bias can actually lead us to make crueler decisions, designing product features with the “happy, upbeat, good-life” ideal user bias can lead us to create crueler user experiences.

“To shield ourselves psychologically from the terrifying thought that the world is full of innocent people suffering,” Burkeman writes, we, as humans, “endorse policies more likely to make that suffering worse.” And by denying the full spectrum of the realities of people’s lives, awesome and tragic, we, as experience designers, do the same. Except we’re the ones with the power to actually do something about it.

“Just to pick two obvious fixes,” Meyer wrote at the end of his post, “First, don’t pre-fill a picture until you’re sure the user actually wants to see pictures from their year. And second, instead of pushing the app at people, maybe ask them if they’d like to try a preview—just a simple yes or no. If they say no, ask if they want to be asked again later, or never again. And then, of course, honor their choices. This is… designing for crisis, or maybe a better term is empathetic design.”

Or how about just, you know, design.

In the wake of Meyer’s post, the product manager for Facebook’s Year in Review app told The Washington Post. “We can do better.”

But four months later, Facebook’s photo collage assault on my friend suggests perhaps they don’t really think they can.

“Faced with evidence of injustice, we’ll certainly try to alleviate it if we can,” Burkeman wrote, “But, if we feel powerless to make things right, we’ll do the next best thing, psychologically speaking: we’ll convince ourselves that the world isn’t so unjust after all.”