Last week, my friend Kris Krug flew down to the Gulf of Mexico on the TEDxOilSpill Expedition, a week-long project to document the crisis in the Gulf and bring a first hand report back to the TEDxOilSpill event in Washington, D.C. on June 28. Kris, a photographer, web strategist, and self-described “cyberpunk anti-hero from the future” (though, technically, from Vancouver) was there as part of the team of photographers, videographers, and writer traveling through Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana documenting the current situation in the coastal communities affected by the oil spill. (Kris’s shots from the expedition have also appeared in National Geographic photo essays: 1, 2, 3).

Talking with Kris — who has been one of the earliest and staunchest supporters of my writing here at Social-Creature (the header image on this site is one of his photos) — he suggested that while it’s not my usual ‘beat,’ if I felt so inspired, I should write some words about this situation.

Early morning thunderstorm off the coast of Grand Isle, Louisiana.

The truth is that there is something in this endlessly tragic mire which I’ve kept thinking about over and over during the course of the now 69 days since the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded. And that recurring thought — beyond how devastating and heartbreaking this entire situation is — is how utterly foreign and disturbing it feels to be this completely powerless to do anything about it.

As a generation, mine has not known powerlessness. We have known no great war. No great depression. We were born a decade after the last U.S. draft ended. Our childhoods were filled with images like these:

We were weaned on the sense that something could be done. A single person could stand up to a row of tanks in Tiananmen Square. People could tear the Berlin wall down. People could undo the totalitarian Soviet regime. By the time we got to high school, the Internet had arrived, followed quickly by college and the birth of the social web. The digital revolution added an unprecedented amplification to this sense of our own personal agency. Just over the past few short years we have experienced how sites like Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook have offered platforms for us to do something.

Last summer, the Washington Post called the aftermath of the Iran election a “A Twitter Revolution.” As police tried to suppress demonstrators who took to the streets to protest the declared results of the presidential elections in a place halfway around the planet, Twitter let the world know exactly what was going on, on the ground in Iran even as outside journalists were barred from the country. It was instantaneous, unfiltered, real, and it compelled our attention. The U.S. State Department even asked Twitter to delay scheduled maintenance on the site at the time in order avoid disrupting communications among tweeting Iranian citizens and the rest of the world. Ordinary voices of dissent had never had access to such mass media before, and just bearing witness, just knowing their struggle, just retweeting and communicating was an act of solidarity with those citizens of Iran who were protesting, and an act of defiance against the forces that would have them silenced. It was doing something.

Six months ago, after a 7.0 magnitude earthquake devastated Haiti, a place of no real political or economic importance, these digital tools helped mobilize the aid and compassion of the entire world almost instantly. Within just a few hours a text-based donation service was set up for the American Red Cross’s relief efforts. In just 2 days of the earthquake the program had raised over $5 million from over a half million different mobile phone users. Haitian-born musician Wyclef Jean’s Yele Haiti Foundation, also running its own text donation drive, raised another $1 million. It was a watershed moment. Never had so much money been raised for relief so quickly after a disaster. The digital tools facilitated this, but what drove people to make those donations was the desire to do something even if it was just giving a few dollars to help alleviate suffering.

We humans have such a deep need to feel like we’ve got any sense of agency in our lives, we’ll happily trick ourselves into perceiving we’re in control — or at the very least, that control over chaos is attainable. This proclivity is a large part of why God exists — or rather, why we believe he does. In a 2007 New York Times article exploring possible answers from evolutionary biology as to how we have come to believe in God, Robin Marantz Henig wrote:

Our brains are primed for [belief in the supernatural], ready to presume the presence of agents even when such presence confounds logic.

We automatically, and often unconsciously, look for an explanation of why things happen to us,” Barrett wrote, “and ‘stuff just happens’ is no explanation. Gods, by virtue of their strange physical properties and their mysterious superpowers, make fine candidates for causes of many of these unusual events.” The ancient Greeks believed thunder was the sound of Zeus’s thunderbolt. Similarly, a contemporary woman whose cancer treatment works despite 10-to-1 odds might look for a story to explain her survival. It fits better with her causal-reasoning tool for her recovery to be a miracle, or a reward for prayer, than for it to be just a lucky roll of the dice.

As an alternative to these external supernatural forces it’s become increasingly popular to reclaim a sense of power in the face of chaos or tragedy by elevating control of our inner selves to this transcendent status of godliness. In Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America Barbara Ehrenreich recounts, in a chapter titled, “Smile or Die: The Bright Side of Cancer,” how getting diagnosed with breast cancer led to her first introduction with the cult of “positive thinking.” The “Pink Ribbon Culture,” she writes, is defined by a mantra of “positive thinking” that is so extreme, at times it paints cancer as a “gift, deserving of the most heartfelt gratitude:”

In the mainstream of breast cancer culture there is very little anger, no mention of possible environmental causes, and few comments about the fact that in all but the most advanced, metastasized cases, it is the “treatments,” not the disease, that cause the immediate illness and pain. In fact, the overall tone is almost universally upbeat. The Best Friends Web site, for example, featured a series of inspirational quotes: “Don’t cry over anything that can’t cry over you,” “I cant stop the birds of sorrow from circling my head, but I can stop them from building a nest in my hair,” “When life hands out lemons, squeeze out a smile,” “Don’t wait for your ship to come in… swim out to meet it,” and much more of that ilk.

The cheerfulness of breast cancer culture goes beyond mere absence of anger to what looks all too often, like a positive embrace of the disease. As “Mary” reports, on the Bosom Buds message board: “I really believe I am a much more sensitive and thoughtful person now. I was a real worrier before. Now I don’t want to waste my energy on worrying. I enjoy life so much more now and in a lot of aspects I am much happier now.” [Another] such testimony to the redemptive powers of the disease: “I can honestly say I am happier now than I have ever been in my life — even before the breast cancer.

One survivor turned author credits it with revelatory powers, writing in her book The Gift of Cancer: A Call to Awakening that “cancer is your ticket to your real life. Cancer is your passport to the life you were truly meant to live. Cancer will lead you to God. Let me say that again. Cancer is your connection to the Divine.”

The effect of all this positive thinking is to transform breast cancer [from] an injustice or tragedy to rail against.

There was, I learned, an urgent medical reason to embrace cancer with a smile: a “positive attitude” is supposedly essential to recovery. It remains almost axiomatic, within the breast cancer culture, that survival hinges on “attitude”…. [the belief] that a positive attitude boosts the immune system, empowering it to battle cancer more effectively.

You’ve probably read that assertion so often, in one form or another, that it glides by without a moment’s thought about what the immune system is, how it might be affected by emotions, and what, if anything, it could do to fight cancer. The business of the immune system is to defend the body against foreign intruders, such as microbes, and it does so with a a huge onslaught of cells and whole cascades of different molecular weapons.

In 1970, the famed Australian medical researcher McFarlane Burnet had proposed that the immune system is engaged in constant “surveillance” for cancer cells, which, supposedly, it would destroy upon detection. Presumably, the immune system was engaged in busily destroying cancer cells — until the day came when it was too exhausted (for example, by stress) to eliminate the renegades. There was at least one a priori problem with this hypothesis: unlike microbes, cancer cells are not “foreign”; they are ordinary tissue cells that have mutated and are not necessarily recognizable as enemy cells. As a recent editorial in the Journal of Clinical Oncology put it: “What we must first remember is that the immune system is designed to detect foreign invaders, and avoid our own cells. With few exceptions, the immune system does not appear to recognize cancers within an individual as foreign, because they are actually part of the self.”

More to the point, there is no consistent evidence that the immune system fights cancers, with the exception of those cancers caused by viruses, which may be more truly “foreign.” People whose immune systems have been depleted by HIV or animals rendered immunodeficient are not especially susceptible to cancers, as the “immune surveillance” theory would predict. Nor would it make much sense to treat cancer with chemotherapy, which suppresses the immune system, if the latter were truly crucial to fighting the disease. Furthermore, no one has found a way to cure cancer by boosting the immune system with chemical or biological agents.

But despite all the evidence to the contrary, you can see the appeal of believing in the power of “positive thinking” anyway, can’t you? Instead of waiting passively for the treatments to kick in, breast cancer patients can now “work on themselves;” monitor their moods and “psychic energies.” In other words, the idea of a link between subjective feelings and the disease, fabricated though it may be, gives cancer patient something to do.

And this applies far beyond cancer, to any kind of overpowering misfortune. “We’re always being told that looking on the bright side is good for us,” writes Thomas Frank, author of What’s the Matter With Kansas?, in a review on the back cover of Bright-Sided, “But now we see that it’s a great way to brush off poverty, disease, and unemployment, to rationalize an order where all the rewards go to those on top. The people who are sick or jobless — why, they just aren’t thinking positively. They have no one to blame but themselves.”

It’s not that we’re assholes. It’s just that we desperately want to believe the world is a far more just place than it actually is. As David McRaney, journalist, and author of You Are Not So Smart, a blog about the workings of self-delusion, writes in a post about The Just World Fallacy, humans have “a tendency to react to horrible misfortune, like homelessness or drug addiction, by believing the people stuck in horrible situations must have done something to deserve it.” Here is the Just World fallacy in action:

.

Oh, wait. Actually, THAT guy IS an asshole. As is Rhonda Byrne, creator of “The Secret,” who, in the wake of the 2006 tsunami, citing the law of attraction, announced that disasters like that can happen only to those who are “on the same frequency as the event.”

A flock of Brown Pelicans on some rocks in Alabama.

While, clearly, suggesting that the poor little pelicans (or anyone else) signed a deal with the devil or somehow attracted the oil spill upon themselves is just waaaay the fuck further out in looney-land than anyone who is not an asshole cares to travel, at their base, all these delusions are simply coping mechanisms. A way to synthesize a sense of being less powerless than you really are; a way to deal in the face of extreme evidence to the contrary. Because the reality is that feeling like we have NO control whatsoever, like our lives are simply dried up leaves in the autumn winds of chaos, like any choices we make are utterly meaningless and futile is actually terrible for our mental well-being and our health. Note: this is not the same as saying “thinking positive will cure your cancer,” it’s saying that extreme stress factors are, indeed, bad for you. Duh. “Torture a lab animal long enough,” Ehrenreich writes, “as the famous stress investigator Hans Selye did in the 1930s, and it becomes less healthy and resistant to disease.” In a post on Learned Helplessness — McRaney writes:

If, over the course of your life, you have experienced crushing defeat or pummeling abuse or loss of control, you learn over time there is no escape, and if escape is offered, you will not act – you become a nihilist who trusts futility above optimism.

Studies of the clinically depressed show that when they fail they often just give in to defeat and stop trying.

A study in 1976 by Langer and Rodin showed in nursing homes where conformity and passivity is encouraged and every whim is attended to, the health and wellbeing of the patients declines rapidly. If, instead, the people in these homes are given responsibilities and choices, they remain healthy and active.

This research was repeated in prisons. Sure enough, just letting prisoners move furniture and control the television kept them from developing health problems and staging revolts.

In homeless shelters where people can’t pick out their own beds or choose what to eat, the residents are less likely to try and get a job or find an apartment.

The underlying thread here is always about control, or the loss of it. Chaos is unbelievably traumatizing — personally, and to us as a species. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine, have been studying the impact of the 9/11 attacks on male babies since 2005. Their just recently published findings reveal that in the aftermath of the 2001 tragedy pregnant women miscarried a disproportionate number of male fetuses. In September 2001, the death rate of male fetuses compared with female increased by 12 percent. That’s 120 extra losses in a single month. The theory behind this phenomenon is likely an evolutionary adaptation. Women have adapted to produce what, Tim Bruckner, the study’s lead author and a professor at UC Irvine, describes as “the alpha male.” Which could explain why male fetuses are more sensitive to their mothers’ stress hormones than female ones. When a pregnant woman experiences some sort of crisis — whether personal or not — her male baby is more vulnerable to be miscarried. In times of prosperity and security, male fetuses are more likely to be brought to term, because there’s a greater chance that they’ll be healthy and robust. During periods of scarcity, however, male miscarriages are much more common. Indeed, the phenomenon reported by Bruckner & Co. has been observed before — reduced male birth rates have been reported during other instances of national stress or suffering, like economic recessions or natural disasters.

Surface oil burns in the Gulf of Mexico as part of the oil spill clean-up.

Which brings us back to the Gulf of Mexico and the worst environmental disaster in US history; the cold, strange, numbing sense of a profound national powerlessness seeping in as we see sickening photos of helpless animals drowning in oil. Just thinking about how you can’t do anything about it for too long will make you want to check the fuck out of this whole story. I know. I want, as much as anyone else, to have something to be able to do to make all of this stop.

To a large extent this is completely new territory for my generation. Nationally, we have never been faced with something we couldn’t “do” something about. As the child of parents who lived through WWII, Refuseniks, no less — the 1 and a half million Russian Jews who were trapped in the Soviet Union, denied permission by the government to leave the country, in my parents’ case, for a decade — I know, personally, just how sheltered my generation’s childhood has been in contrast. It’s unprecedented for us. We’ve had so little practice at facing situations where we couldn’t just do something, at fighting them, at living through them. Not 9/11, not the financial crisis, not the wars in between, it’s this oil spill that is my generation’s unfortunate turn to figure out how to stand in the face of powerlessness.

In a Huffington Post piece a few weeks ago on why he “Co-opted BP’s Twitter Presence,” Leroy Stick, the alleged name behind the anonymous @BPGlobalPR twitter account, which posts ingeniously scathing commentary on BP with satire so black as to befit the disaster the company has wrought, wrote:

I started @BPGlobalPR because the oil spill had been going on for almost a month and all BP had to offer were bullshit PR statements. No solutions, no urgency, no sincerity, no nothing. That’s why I decided to relate to the public for them. I started off just making jokes at their expense with a few friends, but now it has turned into something of a movement. As I write this, we have 100,000 followers and counting. [Currently, almost 179,000]. People are sharing billboards, music, graphic art, videos and most importantly information.

If you are angry, speak up. Don’t let people forget what has happened here. Don’t let the prolonged nature of this tragedy numb you to its severity. Re-branding doesn’t work if we don’t let it, so let’s hold BP’s feet to the fire. Let’s make them own up to and fix their mistakes NOW and most importantly, let’s make sure we don’t let them do this again.

Right now, PR is all about brand protection. All I’m suggesting is that we use that energy to work on human progression. Until then, I guess we’ve still got jokes.

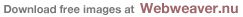

A small quote of inspiration to the affected fishing community at a bait and tackle in Dauphin Island, Alabama

In the introduction to Bright-Sided, Ehrenreich writes:

Americans did not start out as positive thinkers…. In the Declaration of Independence, the founding fathers pledged to one another “our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.” They knew that they had no certainty of winning the war for independence and that they were taking a mortal risk. Just the act of signing the declaration made them all traitors to the crown, and treason was a crime punishable by execution. The point is, they fought anyway. There is a vast difference between positive thinking and existential courage.

We must find that courage now. To keep paying attention. To not tune out the story of this tragedy. To not let futility or apathy or simple delusion take over. We must have the courage to see things as they really are, to bear witness to what’s happening in the gulf, and we must have the courage to fight for answers, to fight for institutional change in the policies that have lead to this disaster, and to work for new solutions. The TEDxOilSpill event I mentioned at the beginning of this post, which is bringing together researchers and leaders to explore new ideas for our energy future, and how we can mitigate the crisis in the Gulf, is a start. There are also currently 126 local Meetups happening in conjunction with the event in 30 countries around the globe. We have to have the courage to do what we can, until we can actually do what we must.

That courage is, literally, what America was founded on, and I hope my generation discovers we too possess a reserve of it.