Jocelyn Marsh wearing headdress by Tiffa Novoa. Image: Brion Topolski, 2005

Right now all across America there is a feather shortage. In April, The Billings Gazette reported:

Jewelry-makers and hairstylists have been snatching up the premium chicken feathers used in standby trout-fly patterns, creating a sudden run on a market that’s ill-prepared for significant fluctuations of demand.

“Supplies are just decimated,” said Jim Cox, co-owner of the Kingfisher fly shop in Missoula, [Montana]. “We just can’t get the premium feathers. Even the (sales) reps for the suppliers can’t get them for themselves.”

What began a couple of years ago as a scattered interest in feather jewelry has erupted into a full-on fad for hair extensions made out of long, slender feathers — the exact same feathers used in the vast majority of traditional dry-fly patterns.

The feathers most valued both by fly-tiers and, lately, fashion mavens come from specific types of roosters that are selectively bred to produce long, slender feathers. Such chickens typically take almost a full year to raise before slaughter. What’s more, they’re rare: Only a few dozen commercial breeders exist in America, and most are small operations.

The situation’s getting so dire, American Public Radio’s Marketplace reports, the American Fly Fishing Trade Association is lobbying lawmakers about conservation. Tom Whiting, owner of Whiting Farms in western Colorado, one of the world’s largest producers of fly tying feathers, a third of whose sales now go to fashion, says, “We have orders far in excess of what we have in our system.” With the demand, the prices are skyrocketing. Last week the Oregonian reported a rooster neck of feathers that would have normally cost $29.95, is now selling for $360. A 300% – 700% jump in rooster saddle feather price is now typical.

In fashion parlance, feathers are in. Steven Tyler has been wearing the avian accessories as he judges American Idol contestants. Pop singer, Kesha, rocks feathers, too, even sticking one in Conan Obrien’s hair during a recent appearance on his show. Between Los Angeles’s mercantile meccas of Melrose Ave. and the Beverly Center you can get feather hair extensions, earrings, necklaces; feathers on boots, shoes, tops, skirts, hats, bras, anything. In the summer of 2011, feathers have become a staple of every sartorial and tonsorial aspect imaginable.

The other day I was asked my opinion as to where this current ubiquity of feathers has come from. But as it turns out, I happen to have something better than an opinion: I have an explanation.

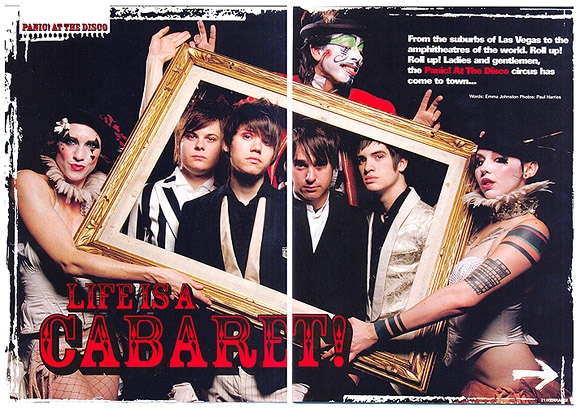

Our story begins almost 12 years ago, in a little town in Oregon, by the name of Ashland, where a group of kids came together to start a circus performance troupe called, El Circo. The group would gain recognition within the Burning Man culture for the extravagant parties they threw at the festival, featuring lavish fire performances, a large, geodesic dome venue, and a top-notch sound system that attracted world-renowned music acts to perform there. In a 2005 San Francisco Bay Guardian article on the effect that the various groups within the Burning Man community have had on San Francisco nightlife — an impact which now extends to the entire west coast’s, and arguably global, dance culture — the writer paid particular attention to the influence of El Circo:

El Circo has fused a musical style and a fashion sense that are major departures from the old rave scene. [They are credited] with creating the postapocalyptic fashions that many now associate with Burning Man. Most of the original El Circo fashions, which convey both tribalism and a sense of whimsy, were designed by member Tiffa Novoa.”

Here are some of the El Circo costumes from their 2005 shows:

That same year, just two years out of college, I stumbled into the role of production manager for a newly-formed, L.A.-based vaudeville cirque troupe called, Lucent Dossier. Through that initial involvement with Lucent I would meet many other circus groups, including El Circo, who were by then based in San Francisco along with The Yard Dogs Road Show and Vau De Vire Society. There was also March Fourth Marching Band in Portland, Clan Destino in Santa Barbara, and Cirque Berzerk, and Mutaytor in L.A. As these acts grew, the I-5 Freeway became a central artery of culture, pumping a distinct combination of art, music, fashion, and performance up and down the west coast. A social scene evolved around these circus troupes the same way the punk subculture sprang up around the bands that defined it. For lack of another term, I’ve referred to this subculture over the years simply as “circus.”

In Freaks and Fire: The Underground Reinvention of the Circus, J. Dee Hill delves into the history and sociology underpinning the alternative culture circus resurgence:

Traditional forms of the tribe, like the village, have almost completely disappeared. Fewer and fewer people live in small communities where their daily interactions bring them in contact with the people they are deeply connected to, either spiritually or economically. Workers in modern corporations are replaceable and no longer bound to each other by the experience of a shared interdependence. The modern individual is preoccupied simultaneously by isolating, immediate concerns of personal survival and the larger, often intangible concerns of war, terror and economic change as transmitted by a now-seamless global media network. The intermediate space of community is not easily reached.

Not by accident, many of the newer, emergent forms of culture include a specifically tribal aspect. A return to tattooing, sacrification, fire performance and drumming, as well as a renewed interest in ritual, has occurred side-by-side with the formation of intentional (if temporary) communities such as the Rainbow Family gatherings and Burning Man festival.

It was at these kinds of festivals, in clubs and at underground raves, that alternative circus acts began appearing in the early 90′s. The performers were young, crazy “freaks” without any formal training who used circus costumes, skills or themes as performative means for expressing their own exaggerated personalities. Many went on to gain formal training or to study the history of the genre, but essentially their relationship to conventional circuses resembled that of outsider art to mainstream art circles. They didn’t really relate to the modern-day circus. They took their cues from something much, much older: the caravan-pulling gypsies.

The phenomenon of alternative circus performance can be seen as the theatrical dimension to one generation’s wholesale rediscovery of the concept of tribe.

And the inexorable feather trend is inextricably linked with this trajectory.

Novoa co-founded El Circo along with Marisa Youlden, a jewelry designer whose pieces accompanied Novoa’s costumes from the beginning. Youlden first used feathers in her pieces in 2000 and recalls this was when Novoa began creating elaborate feather headdresses for the performers. “At first, this was all costuming,” The 2005 Bay Guardian article quoted Matty Dowlen, El Circo’s operations manager, and performer, “but now it’s who I am.” The aesthetic Novoa first envisioned for the El Circo performers evolved into the prêt-à-porter of the circus subculture and became its signature style. Feathers, which had come to define El Circo costumes, became an integral component of the subculture’s street fashion:

Yup, that last one is me. You can’t see the feather in this shot, but trust me, it was there. In the early to mid-aughts (when the photos above were taken) the feather was as de rigueur a cultural signifier within the circus scene as the safety pin was for punks in the late 1970s and early 80s. In fact, back before it was so commonplace as to lose meaning (or induce a national feather shortage), condescending terms for those sporting the look sprang up within the subculture: “Feather mafia,” was one I heard thrown around; “Trustafarian peacock” even made it into UrbanDictionary.com. And then, something else began to happen.

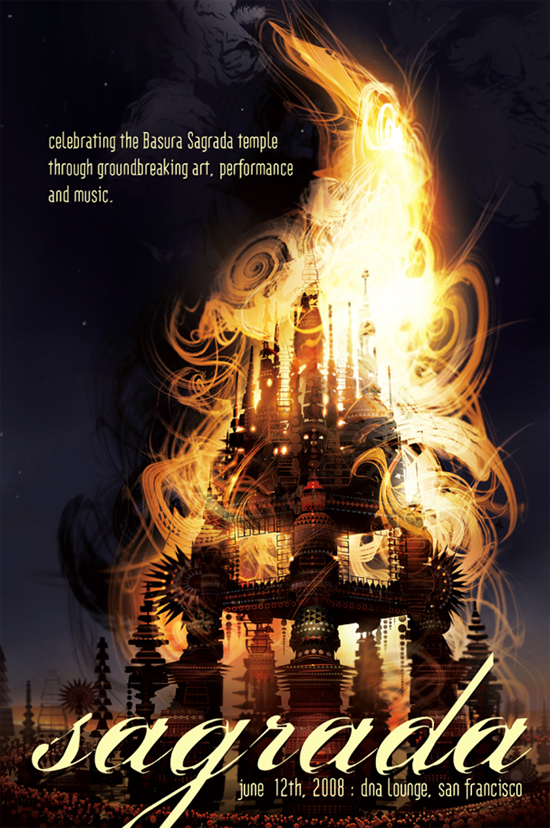

In 2005, Mötley Crüe picked circus as the concept for their comeback tour:

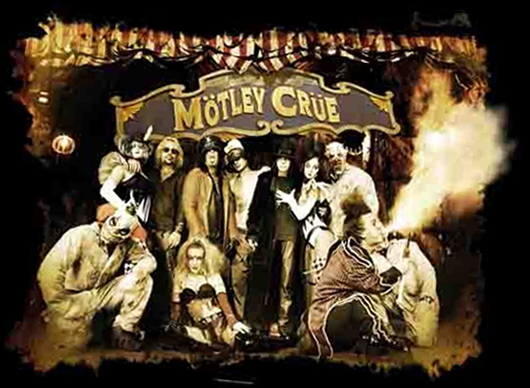

The next year, Panic! At the Disco won an MTV Video Music Award for their circus-themed, “I Write Sins Not Tragedies” video:

A theme they then extended into their “Nothing Rhymes With Circus” tour:

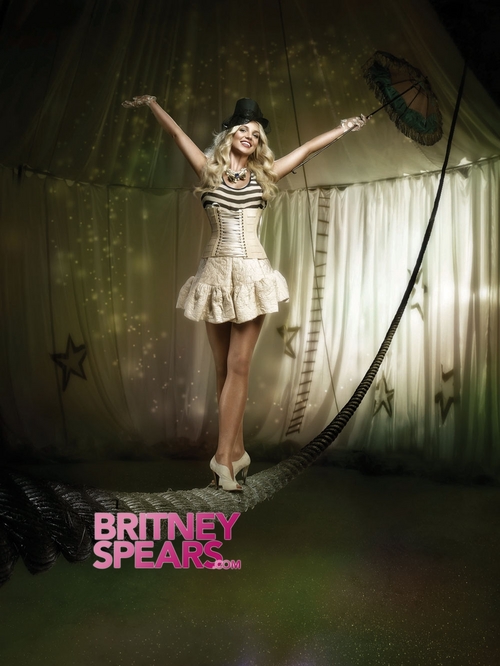

And in 2008, the reigning queen of pop herself at the time, Britney Spears, came out with an album titled, Circus, and ensuing tour of the same theme:

Throughout pop culture, traces of circus’s influence would keep surfacing. The same year as Britney’s Circus album, this was the ad for that season’s America’s Next Top Model:

Or take this ad for the launch of Microsoft’s short-lived Kin mobile device from last year:

The proliferation of circus within pop culture has been directly tied to its growth in underground culture, and being in an underground circus troupe during the height of this infiltration offered backstage access to the proceedings. For example: The circus featured in the Kin ad is March Fourth Marching Band. The circus performers in the Panic! At the Disco music video and tour were members of the troupe I managed. The performers who went on tour with Mötley Crüe would become Lucent Dossier members, as well. Last year, Miley Cyrus’s “Can’t be Tamed” music video featured a winged Cyrus alongside a troupe of be-feathered backup dancers inside a giant birdcage:

Which bears a distinct resemblance to the birdcage (not to mention the aesthetic) Lucent Dossier used prominently in aerial performances during their 2008 residency at the Edison nightclub in Downtown LA.

Especially in Los Angeles, where the Downtown underground and the Hollywood pop culture industry coexist within such proximity of one another, their crossover was inevitable.

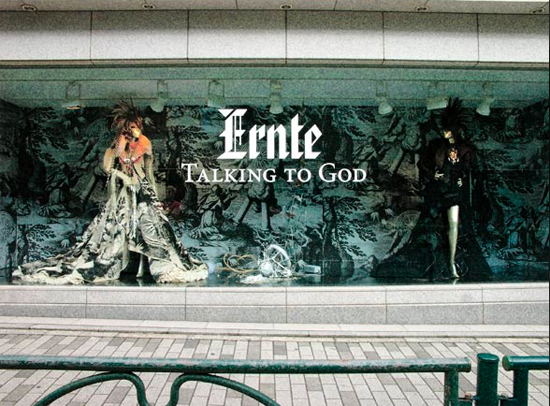

Which brings us back to fashion. In 2002, designers Cassidy Haley and Evan Sugerman, who’d met at Burning Man the year before, founded a fashion label called, Ernte. Two years later, Novoa joined Ernte Fashion Systems, parlaying the aesthetic vision she’d first developed for the circus stage into high fashion. Tragically, in October, 2007, at 32-years-old, Novoa suffered a fatal drug reaction while working in Bali, Indonesia. By then, Ernte had become a globally-renowned haute couture label, retailing in high-end boutiques like Maxfield in Los Angeles, Collete in Paris, and Loveless in Tokyo. Below are some shots of Novoa’s work:

In 2005, Haley went on to form a new label, Skingraft Designs, with Jonny Cota, and later Katie Kay, who was a partner from 2007 – 2010. All three had circus pedigree. Cota and Haley had performed with El Circo, and Kay was one of the original members in Lucent Dossier, for which Haley and Cota would occasionally moonlight. Some of Skingraft’s early work is pictured below.

Since opening their flagship store in Downtown L.A., in 2009, Skingraft’s “post-apocalyptic couture” has graced the celebrity skins of Adam Lambert and The Black Eyed Peas. Rhianna wore a custom Skingraft headdress in her “Rockstar 101″ music video:

And both Britney Spears’ and Beyoncé’s most recent videos are dripping in Skingraft designs. As Skingraft has evolved into an established name within the vocabulary of Los Angeles fashion, countless other apparel designers with circus origins have sprung up in the wings, as it were.

Over the years since Tiffa first put feathers on the bodies of circus performers, inspiring others to follow suit, hundreds of thousands, if not millions have been exposed to the style at Burning Man, and the E3 gaming convention where El Circo would perform; at Coachella, and the Grammy’s afterparty, where Lucent Dossier performed; at countless night clubs stretching from the depths of Downtown L.A. up the length of the Pacific coast. Hollywood stylists partying on Saturday night woke up on Monday with new inspiration. And circus costumers became famed fashion designers. In the end, this cross-pollination laid the foundation for the exact kind of tipping point Malcolm Gladwell describes in his seminal, 2000 book exploring the social mechanics that lead trends to “tip” into mass, cultural phenomena. The Tipping Point begins with the words:

For Hush Puppies — the classic American brushed-suede shoes with the lightweight crepe sole — the Tipping Point came somewhere between late 1994 and early 1995. The brand had been all but dead until that point. Sales were down to 30,000 pairs a year, mostly to backwoods outlets and small-town family stores. Wolverine, the company that makes Hush Puppies, was thinking of phasing out the shoes that made them famous. But then something strange happened. At a fashion shoot, two Hush Puppies executives — Owen Baxter and Geoffrey Lewis — ran into a stylist from New York who told them that the classic Hush Puppies had suddenly become hip in the clubs and bars of downtown Manhattan. “We were being told,” Baxter recalls, “that there were resale shops in the Village, in Soho, where the shoes were being sold. People were going to the Ma and Pa stores, the little stores that still carried them, and buying them up.” Baxter and Lewis were baffled at first. It made no sense to them that shoes that were so obviously out of fashion could make a comeback. “We were told that Isaac Mizrahi was wearing the shoes himself,” Lewis says. “I think it’s fair to say that at the time we had no idea who Isaac Mizrahi was.”

By the fall of 1995, things began to happen in a rush. First the designer John Bartlett called. He wanted to use Hush Puppies in his spring collection. Then another Manhattan deisgner, Anna Sui called, wanting shoes for her show as well. In Los Angeles, the designer Joel Fitzgerald put a twenty-five-foot inflatable basset hound — the symbol of the Hush Puppies brand — on the roof of his Hollywood store and gutted an adjoining art gallery to turn it into a Hush Puppies boutique. While he was still painting and putting up shelves, the actor Pee-wee Herman walked in and asked for a couple pairs. “It was total word of mouth,” Fitzgerald remembers.

In 1995, the company sold 430,000 pairs of the classic Hush Puppies, and the next year it sold four times that, and the year after that, still more, until Hush Puppies were once again a staple of the wardrobe of the young American male. In 1996, Hush Puppies won the prize for best accessory at the Council of Fashion Designers awards dinner at Lincoln Center, and the president of the firm stood up on the stage with Calvin Klein and Donna Karan and accepted an award for an achievement that — as he would be the first to admit — his company had almost nothing to do with. Hush Puppies had suddenly exploded, and it all started with a handful of kids in the East Village and Soho.

How did this happen? Those first few kids, whoever they were, weren’t deliberately trying to promote Hush Puppies. They were wearing them precisely because no one else would wear them. Then the fad spread to two fashion designers who used to shoes to peddle something else — haute couture. The shoes were an incidental touch. No one was trying to make Hush Puppies a trend. Yet, somehow, that’s exactly what happened. The shoes passed a certain point in popularity and they tipped. How does a thirty-dollar pair of shoes go from a handful of downtown Manhattan hipsters to every mall in America in the space of two years?

Right now, the roosters know, but they’re not telling.

__________________________________

Special thanks for helping fill in the details and history for this post go to: Arin Ingraham, Siouxzen Kang, Marisa Youlden, and Cassidy Haley.