Technology has gotten so good at degrading people, even its creators are starting to have enough.

Last year I had what you could call an existential crisis. This psychological hangover was induced by the dissolution of an app I’d launched, which had amassed millions of users but not enough money to keep it alive, a divorce from a second startup I co-founded that cost me layer’s fees and the price of a dear friendship, and topped off finally with a roofie of heartbreak.

It felt for a while like I had fallen through the trap door of the universe. I had discovered what everyone up on the floorboards above, walking noisily about, convinced they were going somewhere, was too blind to see: nothing mattered.

While in the void, I saw Apple unveil the Apple Pencil and thought about how vehemently opposed to a product like this Steve Jobs had been during his lifetime. “God gave us 10 styluses,” proclaimed a man not known for a belief in a power higher than himself, “let’s not invent another.” This prophetic aversion had led directly to the invention the iPhone, a touch-screen device that in a few years had wholly remade the world in its self-images.

“As soon as you have a stylus, you’re dead,” Jobs had famously declared. But, of course, at 56, Steve Jobs was dead, and as soon as he was, Apple had a stylus.

“Think about that when you’re fighting for some creative idea at work today,” I’d tell people.

All meaning we ascribed to anything we did with our lives seemed ridiculous; an absurd delusion. I wanted to do nothing. I wanted to pursue nothing. I wanted to create nothing. There was no point to any of it.

All of this felt compounded — and if I stared too long into the glare of the digital sun, perpetuated — by an increasingly paralyzing rupture I was watching run down the fabric of the culture.

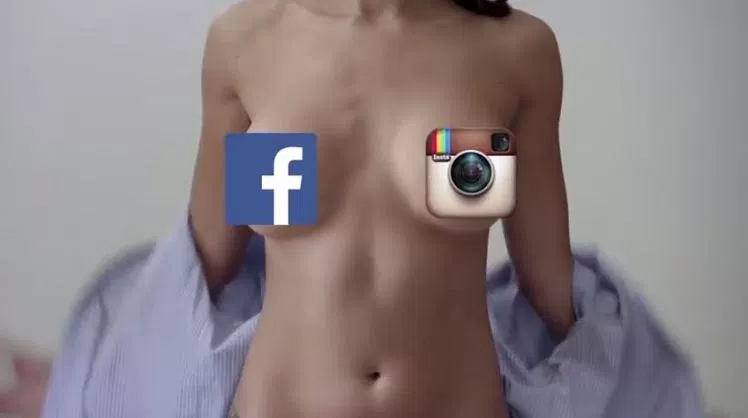

“Our technology is turning us into objects,” I’d written in a 2013 post titled Objectionable, tracing the trajectory from selfies to self-objectification to dehumanization. In a ubiquitously mediated environment, I argued, re-conceiving ourselves and one another as media products was inevitable. “We are all selfies. We are all profiles. We are all objects. And we can’t stop. And the trouble is, it doesn’t matter how you treat objects,” I wrote. “It’s not like they’re people.”

Then came Tinder.

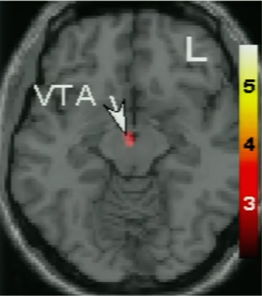

“By reducing people to one-time-use bodies and sex to an on-demand exchange, dating apps have made what they yield us disposable and cheap,” I wrote in an An App For Love. “From swipe to sex, the relentless, grinding repetitiveness inherent in every aspect of the ‘swipe app’ experience sabotages the very mechanics that trigger the brain system for romantic love,” I wrote, referencing Helen Fisher’s extensive neuroscience research on the phenomenon. “Love knows what it likes. And we could be building tech engineered for it — creating a match between the research and the product experience, as it were. But we aren’t. Love has been, literally, written out of the code for a generation afraid to catch feelings. Instead we swipe through thousands of instant people. We learn nothing of them and share nothing of ourselves to be known. We strip ourselves down to anatomy and we become invisible.”

We had succeeded, I wrote in the summer of 2015, in disrupting love. That would be the last thing I’d write before nothing became worth writing about.

In the fall of 2016 there is a toxic sense pervading the culture that no one is deserving of dignity anymore. You can feel it too as you sense your own being swiped away. It’s not just in our politics. It’s in our pockets. It’s in the nameless dread we feel of our devices now. Their myriad manipulations invading our attention, degrading our autonomy, making us sick. One third of us would rather give up sex than our smartphone. The rest of us can’t even get out of bed in the morning without first tapping the black, glass syringe. We have accepted our addiction to digital dopamine so thoroughly we take its unrelenting coercion for granted. We all live under the tyranny of technology now. It’s gotten to the point that even some technology creators are recoiling at the results their creations have wrought on our brave new world, and trying to find ways to design different.

.

PRISONERS OF OUR OWN DEVICE

In “The Scientists Who Make Apps Addictive,” published in The Economist’s 1843 Magazine’s October issue, Ian Leslie writes about Addiction by Design, a book exploring machine gambling in Las Vegas, by anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll:

The capacity of slot machines to keep people transfixed is now the engine of Las Vegas’s economy. Over the last 20 years, roulette wheels and craps tables have been swept away to make space for a new generation of machines: no longer mechanical contraptions (they have no lever), they contain complex computers produced in collaborations between software engineers, mathematicians, script writers and graphic artists.

The casinos aim to maximise what they call “time-on-device”. The environment in which the machines sit is designed to keep people playing. Gamblers can order drinks and food from the screen. Lighting, decor, noise levels, even the way the machines smell — everything is meticulously calibrated. Not just the brightness, but also the angle of the lighting is deliberate: research has found that light drains gamblers’ energy fastest when it hits their foreheads.

But it is the variation in rewards that is the key to time-on-device. The machines are programmed to create near misses: winning symbols appear just above or below the “payline” far more often than chance alone would dictate. Losses are thus reframed as potential wins, motivating [players] to try again. Mathematicians design payout schedules to ensure that people keep playing while they steadily lose money. Alternative schedules are matched to different types of players, with differing appetites for risk: some gamblers are drawn towards the possibility of big wins and big losses, others prefer a drip-feed of little payouts (as a game designer told Schüll, “Some people want to be bled slowly”). The mathematicians are constantly refining their models and experimenting with new ones, wrapping their formulae around the contours of the cerebral cortex.

Gamblers themselves talk about “the machine zone”: a mental state in which their attention is locked into the screen in front of them, and the rest of the world fades away. “You’re in a trance,” one gambler explains to Schüll. “The zone is like a magnet,” says another. “It just pulls you in and holds you there.”

Of course, these days we’re all captive to a screen explicitly designed to exploit our psychology and maximize time-on-device every waking moment, everywhere we go. The average person checks their phone 150 times a day, and each compulsive tug on our own, private slot machine is not the result of conscious choice or weak willpower. It’s engineered.

“There’s a thousand people on the other side of the screen whose job is to break down whatever responsibility I can maintain,” explains Tristan Harris, formerly Google’s Design Ethicist.

Designers, technologists, product managers, data scientists, ad sales executives — the job of all these people, as Harris says, “is to hook people.”

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness starving hysterical,” wrote the beat poet Alan Ginsberg in his 1956 magnum opus, Howl.

Fifty years later, a Harvard math genius named Jeff Hammerbacher would take a job as a research scientist at a startup called Facebook. Hammerbacher would later adapt Ginsberg’s vision for the Millennial era. “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads,” he said.

.

BUT YOU MADE IT IN A SLEAZY WAY

.

There is a huge incentive for technology companies to keep us in thrall to their machine zone. From small startups to the massive, public corporations that are now America’s most valuable companies, the dual motivators of reward from advertisers, and punishment from stockholders or investors compel them to make sure they keep you, me, and everyone we know constantly and increasingly engaged.

From “The Scientists Who Make Apps Addictive”:

The emails that induce you to buy right away, the apps and games that rivet your attention, the online forms that nudge you towards one decision over another: all are designed to hack the human brain and capitalise on its instincts, quirks and flaws.

When you get to the end of an episode of “House of Cards” on Netflix, the next episode plays automatically. It is harder to stop than to carry on. Facebook gives your new profile photo a special prominence in the news feeds of your friends, because it knows that this is a moment when you are vulnerable to social approval, and that “likes” and comments will draw you in repeatedly. LinkedIn sends you an invitation to connect, which gives you a little rush of dopamine — how important I must be! — even though that person probably clicked unthinkingly on a menu of suggested contacts. Unconscious impulses are transformed into social obligations, which compel attention, which is sold for cash.

The same month as the article above came out, Briana Bosker wrote in The Atlantic:

Sites foster a sort of distracted lingering partly by lumping multiple services together. To answer the friend request, we’ll pass by the News Feed, where pictures and auto-play videos seduce us into scrolling through an infinite stream of posts — what Harris calls a “bottomless bowl,” referring to a study that found people eat 73 percent more soup out of self-refilling bowls than out of regular ones, without realizing they’ve consumed extra. Checking that Facebook friend request will take only a few seconds, we reason, though research shows that when interrupted, people take an average of 25 minutes to return to their original task. The “friend request” tab will nudge us to add even more contacts by suggesting “people you may know,” and in a split second, our unconscious impulses cause the cycle to continue on the recipient’s phone.

Food companies engineer flavors to exploit our biological desire for sugary, salty, and fatty foods. Social technology taps into our psychological cravings. We are social creatures, after all.

Bosker writes:

The trend is toward deeper manipulation in ever more sophisticated forms. Harris fears that Snapchat’s tactics for hooking users make Facebook’s look quaint. Facebook automatically tells a message’s sender when the recipient reads the note — a design choice that activates our hardwired sense of social reciprocity and encourages the recipient to respond. Snapchat ups the ante: Unless the default settings are changed, users are informed the instant a friend begins typing a message to them — which effectively makes it a faux pas not to finish a message you start. Harris worries that the app’s Snapstreak feature, which displays how many days in a row two friends have snapped each other and rewards their loyalty with an emoji, seems to have been pulled straight from [Stanford experimental psychologist B.J.] Fogg’s inventory of persuasive tactics. Research shared with Harris by Emily Weinstein, a Harvard doctoral candidate, shows that Snapstreak is driving some teenagers nuts — to the point that before going on vacation, they give friends their log-in information and beg them to snap in their stead. “To be honest, it made me sick to my stomach to hear these anecdotes,” Harris told me.

But aren’t we all feeling a little bit sicker?

.

UNCOMFORTABLY NUMB

“Like many addicts, I had sensed a personal crash coming,” Andrew Sullivan wrote in a September New York Magazine essay about how his relationship to technology nearly destroyed him:

For a decade and a half, I’d been a web obsessive, publishing blog posts multiple times a day, seven days a week, and ultimately corralling a team that curated the web every 20 minutes during peak hours. Each morning began with a full immersion in the stream of internet consciousness and news, jumping from site to site, tweet to tweet, breaking news story to hottest take, scanning countless images and videos, catching up with multiple memes. Throughout the day, I’d cough up an insight or an argument or a joke about what had just occurred or what was happening right now. And at times, as events took over, I’d spend weeks manically grabbing every tiny scrap of a developing story in order to fuse them into a narrative in real time.

I was, in other words, a very early adopter of what we might now call living-in-the-web. And as the years went by, I realized I was no longer alone. Facebook soon gave everyone the equivalent of their own blog and their own audience. More and more people got a smartphone — connecting them instantly to a deluge of febrile content, forcing them to cull and absorb and assimilate the online torrent as relentlessly as I had once. It was ubiquitous now, this virtual living, this never-stopping, this always-updating. I remember when I decided to raise the ante on my blog in 2007 and update every half-hour or so, and my editor looked at me as if I were insane. But the insanity was now banality; the once-unimaginable pace of the professional blogger was now the default for everyone.

If the internet killed you, I used to joke, then I would be the first to find out. Years later, the joke was running thin. In the last year of my blogging life, my health began to give out. Four bronchial infections in 12 months had become progressively harder to kick. Vacations, such as they were, had become mere opportunities for sleep. My dreams were filled with the snippets of code I used each day to update the site. My friendships had atrophied as my time away from the web dwindled. My doctor, dispensing one more course of antibiotics, finally laid it on the line: “Did you really survive HIV to die of the web?”

In an essay on contemplation, the Christian writer Alan Jacobs recently commended the comedian Louis C.K. for withholding smartphones from his children. On the Conan O’Brien show, C.K. explained why: “You need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away,” he said. “Underneath in your life there’s that thing … that forever empty … that knowledge that it’s all for nothing and you’re alone … That’s why we text and drive … because we don’t want to be alone for a second.”

He recalled a moment driving his car when a Bruce Springsteen song came on the radio. It triggered a sudden, unexpected surge of sadness. He instinctively went to pick up his phone and text as many friends as possible. Then he changed his mind, left his phone where it was, and pulled over to the side of the road to weep. He allowed himself for once to be alone with his feelings, to be overwhelmed by them, to experience them with no instant distraction, no digital assist. And then he was able to discover, in a manner now remote from most of us, the relief of crawling out of the hole of misery by himself. As he said of the distracted modern world we now live in: “You never feel completely sad or completely happy, you just feel … kinda satisfied with your products. And then you die. So that’s why I don’t want to get a phone for my kids.”

“When you’re feeling uncertain,” says Nir Eyal, author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, “Before you ask why you’re uncertain, you Google. When you’re lonely, before you’re even conscious of feeling it, you go to Facebook. Before you know you’re bored, you’re on YouTube. Nothing tells you to do these things. The users trigger themselves.”

Technology’s relentless intrusion isn’t just hijacking our attention, it’s being deliberately designed to disrupt another kind of human experience:

Endless distraction is being engineered to prevent us from experiencing emotion. A form of, literally, psychological abuse.

What is this doing to our mental health?

The American College Health Association’s Spring 2016 survey of 95,761 students found that 17% of the nation’s college population has been diagnosed with or treated for anxiety problems during the past year. 13.9% were diagnosed with or treated for depression. Up from 11.6% and 10.7% respectively just five years ago.

The Wall Street Journal reports:

Ohio State has seen a 43% jump in the past five years in the number of students being treated at the university’s counseling center. At the University of Central Florida in Orlando, the increase has been about 12% each year over the past decade. At the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, demand for counseling-center services has increased by 36% in the last seven years.

There is a mental health crisis of, literally, epidemic proportion going on.

The Wall Street Journal suggests it is “unclear why the rates of mental-health problems seem to be increasing.” Anxiety and depression rising in tandem with cohorts of young people who have spent more and more of their lives enmeshed in addictive technology with each successive year may simply be a coincidence.

So, you know, who knows?

.

THE MAN IN THE MIRROR

“I felt powerless,” Justin McLeod recently told writer Nancy Jo Sales.

Last year, Sales’s Vanity Fair article, Tinder and the Dawn of the ‘Dating Apocalypse,’ provided an ethnography of the dystopian dating app culture, but unlike her other subjects, McLeod wasn’t just another helpless user at the mercy of dating app technology. He is the founder of the dating app Hinge.

“It was crazy,” McLeod said. “I had $10 million in the bank. I had resources. I had a team. But as a C.E.O. I felt more powerless than I did when I had, like, no money in the bank and this thing was just getting started.”

“When your article came out,” McLeod had written to Sales back in August, “it was the first among many realizations that Hinge had morphed into something other than what I originally set out to build. Your honest depiction of the dating app landscape has contributed to a massive change we’re making at Hinge later this fall. I wanted to thank you for helping us realize that we needed to make a change.”

McLeod, 32, had launched Hinge in early 2013, fresh out of Harvard Business School, with the hope of becoming the “Match for my generation” — in other words a dating site that would facilitate committed relationships for younger people who were less inclined to use the leading and yet now antiquated (in Internet years) service. He was a bit of a romantic; last November a “Modern Love” column in the New York Times told the story of how he made a mad rush to Zurich to convince his college sweetheart not to marry the man she was engaged to (she and McLeod plan to marry this coming February). So nothing in his makeup nor his original plans for his company fit in with it becoming a way for Wall Street fuckboys to get laid. (“Hinge is my thing,” said a finance bro in my piece, a line McLeod says made him blanch.)

Sales’s article was a reckoning. Within a few months of its publication the Hinge team began conducting user research that, as McLeod writes, “would reveal how alarmingly accurate its indictment of swiping apps was.”

Among Hinge’s findings:

- 7 in 10 surveyed women on the leading swiping app have received sexually explicit messages or images.

- 6 in 10 men on the leading swiping app are looking primarily for flings or entertainment.

- 30% of surveyed women on swiping apps have been lied to about a match’s relationship status.

- 22% of men on Hinge have used a swiping app while on a date.

- 54% of singles on Hinge report feeling lonely after swiping on swiping apps.

- 21% of surveyed users on the leading swiping app have been ghosted after sleeping with a match.

- 81% of Hinge users have never found a long-term relationship on any swiping app.

Unsurprisingly, among the main design conventions McLeod and his team identified that have become standard in swipe apps are: a “slot-machine interface” that encourages people to keep swiping, and the dehumanizing representation of “people as playing cards.” These design choices not only “lead to the pathologically objectifying way many choose to engage with the real humans on the other side of the app” but also serve the business purpose of orienting users “towards engagement, not finding relationships.”

On the eve of Hinge’s relaunch as a completely overhauled product, (sans “swiping, matching, timers and games”), McLeod wrote:

The most popular swiping app boasts that users login on average 11 times per day spending up to 90 minutes per day swiping, and have accumulated on average over 200 matches. However, for the vast majority of users this has led to exactly zero relationships.

Like a casino, a swiping app isn’t designed to help you win; it’s designed to keep you playing so the house wins. Swiping is an addictive game designed to keep you single.

Given the current state of our culture, it’s now more critical than ever that there exist a service that helps those bold enough to seek real relationships find meaningful connections. With it, we hope we can pave the way for a new normal in dating culture that treats people with dignity and helps those seeking relationships find what they’re really looking for.

On October 11 the new Hinge launched on iOS in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and India.

“What responsibility comes with the ability to influence the psychology of a billion people,” asks Tristan Harris. “Behavior design can seem lightweight because it’s mostly just clicking on screens. But what happens when you magnify that into an entire global economy? Then it becomes about power.”

Prior to his appointment as Google’s Design Ethicist, Harris worked on the Gmail Inbox app, which is where he began to think about the ways experience design choices can have ramifications on society at a mass scale. In 2016 Harris left Google to found Time Well Spent, a consultancy that works with tech startups proactively seeking to create more conscious user experiences, and to raise awareness for how digital technology is exploiting our psychology in ways we’ve come to take for granted.

As Bosker writes, Harris’s team at Google “dedicated months to fine-tuning the aesthetics of the Gmail app with the aim of building a more ‘delightful’ email experience. But to him that missed the bigger picture: Instead of trying to improve email, why not ask how email could improve our lives — or, for that matter, whether each design decision was making our lives worse?”

Like McLeod and Harris these are questions technology creators seem to be starting to ask themselves.

“We suck at dealing with abuse and trolls on the platform,” Dick Costolo, Twitter’s former CEO, wrote in a leaked memo in 2015. “We’ve sucked at it for years. It’s no secret. We lose core user after core user by not addressing simple trolling issues that they face every day. I’m frankly ashamed of how poorly we’ve dealt with this issue during my tenure as CEO…. I take PERSONAL responsibility for our failure to deal with this as a company.”

In February of 2015 Costolo was confident the platform would “start kicking these people off right and left,” but the problem might have proven too big for Costolo to solve. Before the end of year, he was out. Now, Costolo’s newly-announced post-Twitter venture, Chorus, is a fitness product aiming, unambiguously, to make people’s lives better.

Gabe Zichermann literally wrote the book on Gamification By Design. Now he focuses his energy on a new startup called Onward, which aims to “transform how people relate to addictive and compulsive behaviors in their lives, giving them more control and overall satisfaction.” The company is working with UCLA-based clinical advisors to design a software product to help people “achieve tech-life balance by reducing the pull from social media, porn, sex, gambling, games or shopping.” Not surprisingly, “Onward is designed and built by a team of expert technologists whose lives have been personally affected by addiction.”

“A new class of tech elites [is] ‘waking up’ to their industry’s unwelcome side effects,” Bosker writes. “For many entrepreneurs, this epiphany has come with age, children, and the peace of mind of having several million in the bank.” Bosker quotes Soren Gordhamer, the creator of Wisdom 2.0, a conference series about maintaining “presence and purpose” in the digital age: “They feel guilty,” Gordhamer says.

Perhaps. Or perhaps the realization of how much power they wield may, for some, eventually broaden their scope of what it is they can do with it. It is worth noting that this nascent trend has arrived as many of the technologists and entrepreneurs responsible for shaping the digital experiences of our lives have matured from scrappy upstarts with something to prove into established industry players. Has success felt as meaningful as they’d imagined it would? Did all their hard work and late nights actually create something of value? Has their impact on the world turned out to be what they’d hoped?

Confronted by this self-reflection some are discovering they have the power, and time yet, to make a change.

.

FLESH AND BONE BY THE TELEPHONE

Y-Combinator, the famous startup incubator that has helped create successes like AirBnB, DropBox, Instacart, Reddit, and more, has a motto —

This is an awesome mantra for founders of a commercial enterprise (and for VCs hoping to get a big return on their investment to preach to startups), but the trouble is, just because people want a thing doesn’t always mean that it’s all that awesome. People, for example, want heroin. That doesn’t necessarily mean that your company ought to make it.

What people want can be hacked. Addiction, in fact, changes the structure of the brain. There is a very fine line between making a thing people want and coercing our desires in the first place. By exploiting our psychological susceptibilities, as Harris says, technology companies “are getting better at getting people to make the choices they want them to make.”

Through Time Well Spent Harris is championing the adoption of design standards that treat users’ psychology with respect rather than as an exploitable resource, a concept he refers to as a “Hippocratic oath” for software creators.

Dating back to the physicians of Ancient Greece, the Hippocratic oath states the obligations and proper conduct of doctors. The pledge is taken upon graduation from medical school, oftentimes depicted in the shorthand: “first do no harm.”

But industrialists are not doctors — the psychological motivations that compel someone to go through years and years of grueling, expensive training in order to help heal people are often not the same as those of someone who self-selects to drop out of college to start a company that gives people what they want even if it’s kinda pretty bad for them — it turns out.

As Leslie writes in The Scientists Who Make Apps Addictive:

The biggest obstacle to incorporating ethical design and “agency” is not technical complexity. According to Harris, it’s a “will thing.” And on that front, even his supporters worry that the culture of Silicon Valley may be inherently at odds with anything that undermines engagement or growth. “This is not the place where people tend to want to slow down and be deliberate about their actions and how their actions impact others,” says Jason Fried, who has spent the past 12 years running Basecamp, a project-management tool. “They want to make things more sugary and more tasty, and pull you in, and justify billions of dollars of valuation and hundreds of millions of dollars [in] VC funds.”

In the Atlantic, Josh Elman, “a Silicon Valley veteran with the venture-capital firm Greylock Partners,” offers another analogous example. “Elman compares the tech industry to Big Tobacco.”

New guidelines released by the American Academy of Pediatrics in October exhort app developers to “cease making apps for children younger than 18 months until evidence of benefit is demonstrated.” And “Eliminate advertising and unhealthy messages on apps” for kids five and younger.

But the question is — who’s going to hold them accountable when, inevitably, they don’t? Big Tobacco did not decide to stop advertising to children, and fast food chains didn’t decide to start disclosing the caloric content of their products out of the goodness of their black lungs and arterially-sclerosed hearts. It seems unlikely that relying on the personal conscience of each individual app developer to guide them towards moral integrity is really going to be a scalable solution.

We take it for granted now, that cars have seat-belts to keep the squishy humans inside from flying through a meat-grinder of glass and metal during a collision. But they didn’t always.

How did we ever get so clever?

Regulation. It took legislation to make seat belts standard in cars. And more legislation to require their use. And it has saved lives. Regulation changes not only what’s legal, but what’s normal. Car manufacturers didn’t used to talk about seat belts because it made people think of the reality of car crashes, and cars were sold on the “fantasy” of driving. Now cars are sold on safety.

In the wake of a national mental health crisis and corporations setting out to explicitly exploit our psychology, it’s worth considering the options we have as citizens, not just consumers.

.

SOME COURTESY, SOME SYMPATHY, AND SOME TASTE

In the early 2010’s, Wired founder Kevin Kelly’s book, What Technology Wants, became quite fashionable with a certain type of tech person for absolving himself of any moral or ethical responsibility in his creations. According to this mechanistic faith, technology just wants to, like, live its true self; who are its creators to have any say in the inevitable?

In this vision we are all trapped in a mobius loop of technological determinism. Product creators are powerless to do anything but give people what they want and users are helpless to resist coercion into what they’re given and all of us are slaves to whatever technology wants. No one is accountable while everyone loses dignity.

Yet it is the very power to create products used by millions, or billions of people that is the power to shape — or misshape—the world. Technology wants to irradiate us as much as it wants to cure us. Technology wants to bomb our cities as much as it wants to power them. Technology wants to destroy us as much as it wants to save us. Which is to say, technology wants NOTHING. Technology has no innately arising desires of its own independent of the desires of the people who create it.

At some point in the past 70 years we seem to have forgotten what we knew in the aftermath of WW2, which is that what technology wants is in the eyes of its creators. And engineering technology for objectification, addiction, psychological exploitation, mental abuse….is degrading. It’s degrading to the people who use it, and it’s degrading to the people who make it — it takes a certain kind of personality to feel good depriving people of their humanity, and not everyone has it. You might be one of those with a resistance.

From Andrew Carnegie to Bill Gates some of the most successful technology entrepreneurs, and humans, in history have ended up pursuing ways to contribute to the world after they retired from their commercial endeavors. Perhaps for some in the new generation the prospect of segregating the two is no longer quite as appealing.

In the end, after every single tech CEO alive today is dead, their company, should it outlive them, will make the product they never wanted to see in the world. Some, it seems, are starting to ask themselves whether it’s what they want to be doing while they’re still living.