5 Days & Nights With Startup Millennials in San Francisco.

THURSDAY MORNING: San Francisco’s Hottest Zip Code

.

“Our power was out this morning,” The text message from S, the 27-year-old CTO of a fashion startup in San Francisco reads, “And hopefully it is back on now but… ?”

In Los Angeles, I receive this information as I’m heading out the door to LAX on my way “upstairs” to San Francisco for the Chief Innovation Officer Summit and some meetings. The salient-seeming text arrives, and evaporates like rising steam, pushed into the abyss beyond my screen by more incoming iMessage bubbles of instructions about S’s street address, the lockbox code to get the keys to her apartment, how to locate her room, disclaimers about the room’s condition (Um, it’s a little bit of a disaster because basically every day I drop my clothes on the floor and grab new clothes to wear horizontal line mouth emoji), etc.

As I’m waiting to board one of Southwest’s hourly nerd bird flights from LA and SF, I see an article on the Verge titled, “Crashing the Casting Call For 94110, a Show About San Francisco’s Hottest Zip Code”:

Last month fliers began appearing on certain blocks of San Francisco advertising open auditions for a television pilot about “six leading technology executives living, learning, and loving together in San Francisco’s Mission District.” The shlocky concept was named 94110 after the neighborhood’s zip code, and was roundly ridiculed online. Nonetheless, nearly 100 hopefuls showed up for the casting call this weekend, which was held at SFAQ, a dinged-up, lived-in little art gallery in the Tenderloin.

94110 is S’s zip code.

At this moment my return flight is scheduled for 2 days from now. When I eventually leave, nearly a week later, the power in S’s apartment will still not be fixed.

THURSDAY EVENING: What Is My Mother No Longer Doing For Me?

.

I arrive just in time to catch the end of day 1 of the Chief Innovation Officer Summit. It’s at the Hyatt Regency in the Embarcadero and I can generally remember how to get there from the Mission even without the help of the Google Maps app.

The first time I came to San Francisco I was 12 and I fell in love. In high school, I’d visit every spring break, sitting on top of Nob Hill writing sprawling love poems to the gorgeous city, taking the 24 up Divisadero imagining which house the interview in Interview With The Vampire had taken place in, trying on hippie eyelet dresses in the stores on Haight, which still smelled of nag champa when I wore one to prom. The day after my last final freshman year of college I got on a plane and moved there. I was 18 and San Francisco was full of artists, musicians, dancers, and cultural rebels. It was a totally different city, peopled by totally different kinds of residents.

Watching my fellow riders on the inbound J train now, I am reminded of a census statistic I’d seen recently — between 1990 and 2010 San Francisco’s black population fell 35.7 percent.

In the evening, I meet up with a friend who is a data scientist at an on-demand meal delivery app (think: Tinder for dinner). He tells me he is working on optimizing the food display options for conversion — making sure users would be more likely to see meals they were going to want to order more quickly as soon as they opened the app.

“The tech industry used to think big,” Farhad Manjoo wrote in the New York Times:

As early as 1977, when personal computers were expensive and impractical mystery boxes with no apparent utility or business prospects, the young Bill Gates and Paul Allen were already working toward a future in which we would see “a computer on every desk and in every home.” And in the late 1990s, when it was far from clear that they would ever make a penny from their unusual search engine, the audacious founders of Google were planning to organize every bit of data on the planet — and make it available to everyone, free.

These were dreams of vast breadth: The founders of Microsoft, Google, Facebook and many of the rest of today’s tech giants were not content to win over just some people to their future. They weren’t going after simply the rich, or Americans or Westerners. They planned to radically alter how the world did business so the impossible became a reality for everyone.

We are once again living in a go-go time for tech, but there are few signs that the most consequential fruits of the boom have reached the masses. Instead, the boom is characterized by a rise in so-called on-demand services aimed at the wealthy and the young.

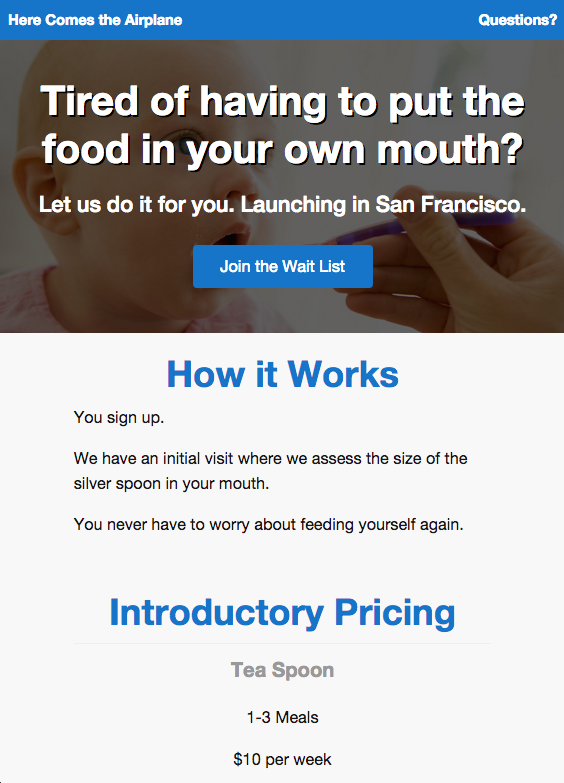

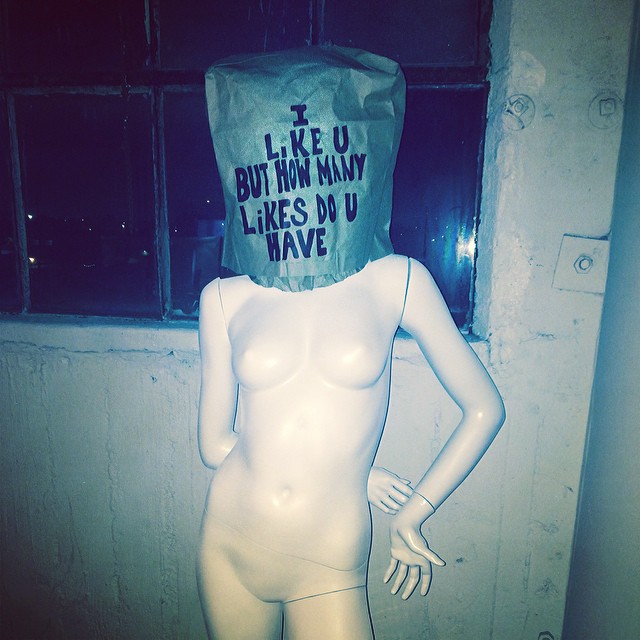

With a few taps on a phone, for a fee, today’s hottest start-ups will help people on the lowest rungs of the 1 percent live like their betters in the 0.1 percent. These services give the modestly wealthy a chance to enjoy the cooks, cleaners, drivers, personal assistants and all the other lavish appointments that have defined extravagant wealth. As one critic tweeted, San Francisco’s tech industry “is focused on solving one problem: What is my mother no longer doing for me?”

During dinner, S texts me. Her roommate, R, has “Somehow acquired this awesome house for the night. So… I’m going to go there to hot tub. Come. It’s like $1,000/night but he got it for free, so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. ALSO the power is still fucked.”

“Ooofff,” I text back. “Mostly cuz my phone.”

“Fortunately, I’m an engineer. So I connected the light in my room to an extension cord. So you can swap the light for your phone maybe?”

“I like how you’re like, ‘Power is fucked. Oh well. We’ll go to another house.

¯\(°_o)/¯.’”

“I mean we flipped all the breakers in our house. And the apartment upstairs. It’s like, fuck it. The door doesn’t close unless you kick it hard. Landlord is coming tomorrow. We have to hide the cat.”

“#SoSF.”

“If you want to stop by to say hi, it’s — “

FRIDAY MORNING: How Do We Adapt To Millennials?

.

At The CIO Summit Day 2, Debra Brackeen, the head of the Innovation Network at Citi is talking about biometric integration with financial data, and I’m sipping grapefruit juice and eating a muffin and thinking — who could have predicted the sci-fi future would be so mundane when it arrived, you know?

Everyone is dressed like they’re running for office. I am definitely feeling like a spy; witnessing the ghost of Christmas future. “How do we adapt to Millennials,” someone asks during Heather McGlinn, Wells Fargo’s SVP, Strategy’s, presentation, “Leveraging Disruptive Technologies to Enhance Competitive Advantages,” in the way that you talk about a group of people when they’re not in the room. And, I mean, they aren’t. At the moment, the Millennials are stumbling into their startups after partying all night at Airbnb mansions on drugs from Silk Road.

All roads lead to discussions of disruption. Tim Sutton, the Global Head of Innovation at Clear explains how companies now need to grow their business minimum 4% every year just to maintain market share. If you’re really just maintaining, you’re actually falling behind. A dilemma since, as he puts it, “There is no white space in a consumer’s wallet.” And meanwhile, somewhere beyond the Hyatt’s glass walls, out there in the fog of war of San Francisco, an army of barbarians wages daily assault on the gates of the establishment, gaining ground even if they lose, simply through chaos.

Citing the New York Times’ leaked 2014 Innovation Report, Jill Lepore wrote in The New Yorker:

Disruption is a predictable pattern across many industries in which fledgling companies use new technology to offer cheaper and inferior alternatives to products sold by established players (think Toyota taking on Detroit decades ago). Today, a pack of news startups are hoping to ‘disrupt’ our industry by attacking the strongest incumbent.”

A pack of attacking startups sounds something like a pack of ravenous hyenas, but, generally, the rhetoric of disruption—a language of panic, fear, asymmetry, and disorder—calls on the rhetoric of another kind of conflict, in which an upstart refuses to play by the established rules of engagement, and blows things up. Don’t think of Toyota taking on Detroit. Startups are ruthless and leaderless and unrestrained, and they seem so tiny and powerless, until you realize, but only after it’s too late, that they’re devastatingly dangerous: Bang! Ka-boom! Think of it this way: the Times is a nation-state; BuzzFeed is stateless. Disruptive innovation is competitive strategy for an age seized by terror.

On a panel about “Strategy Vs Execution,” Pat Conway, the Chief Knowledge Officer for the U.S. Army, is heard saying, “In battle, your biggest obstacle, aside from the adversary, is terrain.”

What must it have been like to awake each morning to an ever-unchanging world? For the majority of humans through the majority of human history this was reality. Today we wake up each morning in a war zone; a disrupted terrorscape where everything has shifted out from under us during the night.

FRIDAY EVENING: You Still Use Skype?

.

I wake up from a nap at 8:30 to a text from S letting me know a car is coming for me and to be ready in 20 minutes. Half of the apartment is still without electricity but an on-demand chauffeur summoned by magic is coming to whisk me off to a secret speakeasy.

“Do you know where we’re going?” I say to the Lyft driver.

“Do you know?”

“Um….. No? I thought you did?”

“When I pick up the next person,” he says noncommittally.

A few minutes later the other passenger gets in. “Do you know where we’re going,” I ask him.

He’s baffled. “Are you going to the same place?”

For a few moments literally no one in this car knows what we’re doing here.

It’s 2015.

Eventually the Lyft driver gets my destination coordinates and drops me off on a street corner in North Beach before driving off to deposit the other Lyft Line passenger. A few moments later S, R, and their respective dates appear. S has Uber (for them), Lyft (for me), and Luxe, an on-demand valet service (for her brother) all running on her phone at the same time.

At the speakeasy I’m telling a story about getting a Skype call on a Virgin flight a couple of years ago. “I was so bewildered I hit the green button without even thinking. And then immediately felt like an asshole and hung up.”

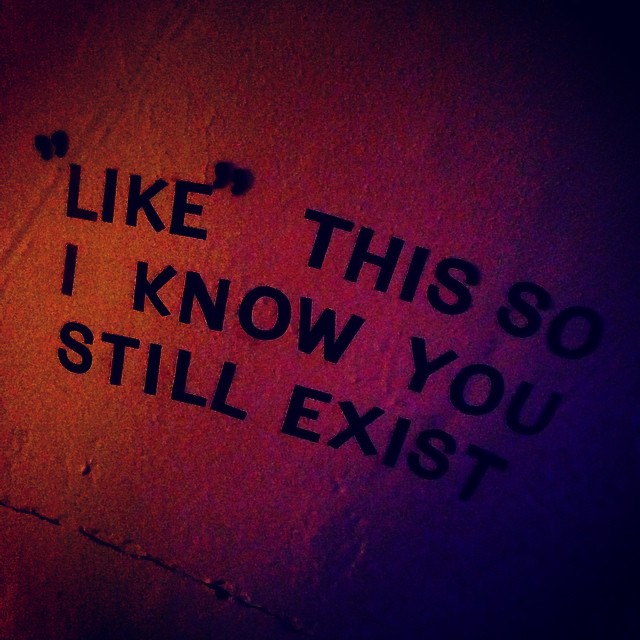

“You still use Skype?” R’s date, a Yale grad who works at Google, deadpans.

This is San Francisco now. Fueled by so much one-upmanship and relentless competitiveness and insecurity. It’s a social world designed, literally, by people who came up playing Dungeons and Dragons, who relish intensely complex systems and arcane rules. The trick to enjoying yourself in San Francisco is not to have very much at stake.

In case you’re curious, 300 million people still use Skype, but the coolest girl you know probably uses a flip phone so.

SATURDAY MORNING: Leaving San Francisco.

Saturday morning everyone is going to Napa and although this was not originally part of the plan, apparently, so am I.

R shows up at the apartment in the morning after You Still Use Skype’s place and while we are waiting for the Luxe valet to bring S’s brother’s car, he tells us a great app idea he’s just thought of: “So it’d basically be Tinder, but just for me. Like that’s all you can do. Is just swipe right on me.” He pauses his rapid-fire delivery to let the concept sink in. “TechCrunch would be all over that. I’d get wifed so fast.”

“Is that what you want, though,” I say.

He considers. “No.”

We spend a while drifting aimlessly as the wait for the Luxe valet lingers on and no one is exactly sure why. Since S ordered the service from her phone she’s the only one who knows the status of what is or might be going on, but S is already in Napa by this point and details are intermittent and sketchy at best. We wonder if perhaps the valet is driving the car out to Napa; is he following her GPS dot around from winery to winery?

The doorbell rings. An electrician arrives to inspect the power outage. A 20th century service while we wait for the 21st century one. Eventually information is absorbed in some kind of vaporous way that the Luxe valet has confused our address with one in San Mateo and after this gets resolved eventually the car arrives and R, S’s brother, and I go to Napa.

SATURDAY EVENING: The Human Centipede Economy.

.

“The Luxe valets use your car to be Lyft drivers,” S says.

“It’s The Human Centipede Economy,” I declare.

R jumps on this and proceeds to map out a full workflow diagram. “Let’s say you start with Airbnb at the top, right? Then below that you’ve got all the property management companies who then all use Homejoy to clean the houses, and Washio for laundry, and Lyft to get around,” and so on and on.

In Napa some people leave our group and new people appear. All day I am the only one who isn’t an engineer. R later explains the difference between engineers, programmers, and developers, but at the moment it’s all the same and we are LOLing and lolling around bucolic winery grounds, wasted on champagne.

“What class of drug is GHB?” Someone asks.

“Drano,” T answers. T is a new addition to our crew. He’s just moved to San Francisco from New York to start a job at a $500-million startup literally the day before. By the second winery he is explaining why he never engages with “torsos” — profiles of headless, chiseled, abdomen selfies — on Grindr, because one time he did, and quickly realized why the guy didn’t include his face.

“I’m actually bi,” he tells me when we go out into the vineyard to take drunken photos amid the leaves.

“Oh, you are?” I say, fiddling with photo filters. “But do you ever just feel like…. you know, paralysis of choice?”

He laughs and I realize this isn’t what he thought I was going to say.

Eventually it becomes evident that I am clearly not heading back to San Francisco tonight and somewhere between Napa and Sacramento I am calling Southwest and changing my return flight.

SUNDAY MORNING: Career Scoping.

.

We wake up in a Mongolian yurt. It’s sunny and warm out here in Colfax, and we are sitting by a pool waiting for breakfast as hawks fly overhead.

People are talking about working at pre / post IPO companies as different career strategies; “making money off the speculation;” “upside.” People are talking about deciding whether to work at Stripe, Slack, Reddit. People are talking about strategically deciding to work at a series B company; “career scoping.”

This is how people talk. And oddly it already feels less grotesque than it did yesterday. We become accustomed to things. These are just the elements of their actual lives. They can’t help it any more than you or I can help the inevitable echo chambers of our lives. We are all stuck in our own myopias.

“Where do you want to work in 25 years?” I ask.

Everyone goes quiet.

S shakes her head. “Oh, that’s not the plan.”

At some point someone says that they don’t really have to work at all.

“But I’m still interested in the power and the money,” R admits. “That’s an optimization scenario I have defined for myself.”

R says this phrase a lot. Life is all an endless string of “optimization scenarios” for maximizing happiness. I suggest that we all generally have a default happiness set point that we can’t really fux with too much; a personal baseline we’d return to eventually no matter if we win the lottery or become paralyzed.

“So, it might not even matter what I do?” He shrugs, grinning, his pink-tinted Aviators reflecting the aquamarine.

SUNDAY EVENING: An SF Trip.

.

“Oh, you’re from LA?” a friend of a friend is saying to me at dinner. I’m back in San Francisco now. It’s cold and dark and the weather feels like the city is spitting at you. “I’m so sorry. LA is terrible.”

“Yup,” I say. “Totally is. You should definitely NOT go there.”

The SF / LA relationship is like a bad breakup where one side never quite got over it. A strangely persistent, one-directional antagonism going back decades in California’s cultural history. “San Francisco is too smug and self-centered for LA,” Ellen Sanders wrote in Trips: Rock Life in the Sixties, “The worst implication you could put on something in or from San Francisco is to call it an LA trip.” Frank Zappa neatly summarized this tension in his autobiography: “No matter how ‘peace-love’ the San Francisco bands might try to make themselves, they eventually had to come south to evil ‘ol Hollywood to get a record deal.”

At dinner I mention a Berkeley Journal of Sociology article by Eric Giannella I’d read recently titled, Silicon Valley’s Amorality Problem, to an ex-Googler:

Silicon Valley’s amorality problem arises from the blind faith many place in progress. The narrative of progress provides moral cover to the tech industry and lulls people into thinking they no longer need to exercise moral judgment.

The progress narrative has a strong hold on Silicon Valley for business and cultural reasons. The successes of science and technology give rise to a faith that rationality itself tends to be a force for good.[4] This faith makes business easier because companies claim to be contributing to progress. Most investors would rather not see their firms get mired in the fraught issue of [morality]; they prefer objective benefits, measured via return on investment. Progress, as we think of it, invites us to cannibalize our moral aspirations with rationality. It leads us to rely on efficiency as a proxy for morality.

There are alternatives to the progress narrative. Many people find meaning in their work through a narrative about making a contribution. Rather than thinking about contribution in a historic sense (i.e., progress), contribution can be thought in terms of specific groups of people.

My dinner companions tell me a story of a recent Airbnb adventure as support of new tech’s contribution. And I understand. I, myself, have just come back from a wonderful Airbnb adventure to a yurt, so, “I get it,” I say. “Airbnb is fun.”

“No, it’s not just fun,” ex-Googler insists. It’s bigger than that.

Downstairs our major cultural contribution is superhero movies. No one producing Avengers 17 or whatever thinks they’re “changing the world.” And that’s OK. Fun is OK. But upstairs it’s different. There is a palpable, existential need for innovation to be righteousness.

“One of the great triumphs of Silicon Valley is its success in framing its companies’ objectives as missions,” John Herman wrote on The Awl in Notes on the Surrender At Menlo Park:

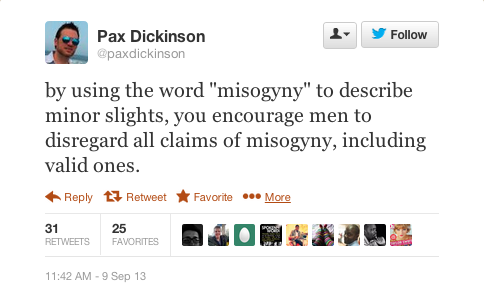

There is a toxic mindset that permeates discussions about most accelerating, inevitable-seeming tech companies. It conflates criticism with denial and nostalgia. Why do people complain about Uber so much? Is it loyalty to yellow cabs and their corrupt nonsense industry? A word of caution about Facebook is not a wish to return to some non-existent ideal time. Worrying about the details of the coming future is merely taking that future seriously. People who insist otherwise? They have their reasons.

Anyway, what were we talking about? This is all going to seem so insane in twenty years. Or two years.

.

Monday Morning: Engineering Sex.

.

This particular Monday it’s Memorial Day, so no one is at work, and S is telling me while blowdrying her hair in the part of the apartment with power, “I have this thing that I do on first dates, where I tell them to meet me at this bar that I know is closed on Mondays, to see how they’ll react. Will they freak out? How will we solve problems together?”

And I’m partly horrified and partly fascinated and partly jealous. Some vital optimization scenario I feel I would have thought of if I was an engineer: how will we solve problems together? It’s like a job interview. “What do you want the reaction to be?” I ask. “Do you want them to pick a new place? Do you want them to ask you to pick?”

“I don’t really care,” S says, “So long as they don’t just freak out.”

I recall the Army’s Chief Knowledge Officer at the CIO Summit talking about “Mission Change;” being able to adapt when the objective suddenly shifts. “Get comfortable with uncomfortableness.” he said; a military zen koan.

R, who is 6’4″, has his own strategy. “My type is really tall girls. Like over 6 feet,” he says, because he knows up there he’s got way less competition.

Back in the car there was a lot of time to kill from Colfax to San Francisco, and we spent it user testing T’s updates to his various dating profiles, which he was retooling from a New York persona to a San Francisco look and feel with the methodical grind of coding. Photos of black Jack Spade jackets overwritten by green zip-up-hoodies.

Everyone was on Tinder of course. S mostly used Hinge. They knew of the League but no one was on it. R said recently he’d been meeting girls offline. “It just works better,” he said, “Cause in real life you get my personality, and that compensates.”

“Do you guys use Snapchat?” I asked.

“I use it to send dick pics to the girls I’m seeing,” R said.

“Do you include the face,” T wanted to know.

“Yeah. I’ve got a go-to angle,” R said, sliding down in the backseat, positioning his hand between his legs. “It makes my dick look huge.”

In Sacramento we saw the Capitol building and R and T took a selfie and sent it to a mutual ex who is a professional dominatrix. At one point she used to be T’s sexcam show partner.

She texted back: “:)”

When we came back to San Francisco, R was telling me a story about a girl he’d started seeing recently. It was nearly midnight and I’d plugged an electric kettle into an overflowing power strip in a part of the apartment with electricity and made some hot chocolate and we sat by the fireplace in the living room and tried to stay warm.

“She asked me, ‘What’s your favorite porn site?’ And I said, no, you write down yours on a piece of paper and then I’ll do the same, and when we swapped, it turned out we’d both written down the same one.”

“One night, we’re having sex and she says, ‘I think you’re bleeding.’ And I turn on the lights and I realize I’ve got a nosebleed and it’s bad. There’s blood everywhere. On the walls, pooled in the sheets. It’s in her hair, all over her face, her tits” — as he’s describing what I can only picture as a murder scene I realize he’s titillated. “We both came harder than we ever had before. She has this framed poster of the Black Dahlia on her wall and some blood got on that and she just never cleaned it off and when I come over it’s still there.”

“But you know,” he went on, “There is one girl…. I’ve known her a long time. She’s the sister of my best friend growing up. I’ve been in love with her my whole life. She’s not even super tall or anything. But she’s just got this look about her, you know? I’d ask her to marry me tomorrow if I thought that she would say yes. But I know she won’t. We still hook up sometimes when we see each other. But she’s, you know, dating some other guy, and she’s in LA…”

Then he got a text from one of the girls he was sleeping with and disappeared into that strange netherworld between the Lyft there and the Lyft back.

MONDAY EVENING: Mission Change.

.

On the flight back to LA I’m watching a Keeping Up With the Kardashians special about Bruce, pre-Caitlyn, Jenner, play silently on the iPad of the girl to my left. On my right, a woman is coordinating logistics for some kind of shoot tomorrow morning. “Get the releases for them,” she’s saying. “They’re in the second drawer. I have to go. We’re about to land.”

I guess this is what we do now. We talk on the phone on airplanes.

She is not using Skype.

San Francisco is like one of those ancient cities now — the kind that has an entirely new city built right on top of it. The people I knew in San Francisco as a teenager and in my 20s all moved out. And in their place, a new and different generation has moved in like fog, obscuring what was there before and transforming the analog into the Cloud. You have to abandon your memory, if you have it, of San Francisco the way it was, and approach it as a totally new American city that now exists on the map. A city with its own new set of social dynamics and value systems, peopled by systems nerds concerned with optimization scenarios not only for the products they create but, by extension, everything else: from dating to careers to transportation to dinner. This is their contribution to our culture (for better or worse).

As we descend into LAX I think about watching the hawks flying overhead on Sunday morning out at the yurt, as we stared up at the sky, looking up from the pool and being blinded by the sun. They circled us like prey as we ate poached eggs. Someone recited trivia about how hawks fly. They catch pockets of hot air, and glide. Predators don’t even flap their wings. They just rise.

@babiejenks

@babiejenks

@babiejenks

@babiejenks