Guns N’ Roses backstage at the Stardust – Los Angeles, 1985 / Image: Reckless Road

Some friends came through town on tour, and sitting around in the dressing room backstage at House of Blues during the opening act, we started talking about the most epic-est, rock-‘n’-rollingest backstages we wished we could have gotten to been a part of. Guns N’ Roses, Mötley Crüe, The Rolling Stones. You know, the usual acts that had come to represent the platonic ideal of the Rock Star. This conversation was instigated by an admission from the main act himself about how boring it was backstage. Thinking back on the venues and the bands I’ve worked with, and even the vaudeville circus I used to manage, it occurred to me that (aside from a few exceptions working with music festivals — notably, on the production rather than the performance side — which only served to prove the rule) almost all the backstages I’ve ever been in were basically boring. Sure, there was always the inevitable adrenaline of last-minute chaos and ego trips and personality clashes and whatnot, but the debauched excess of the truly rock ‘n’ roll antics of yore? Even the folks on the tour, who would, that night, go on to rock the faces off twelve hundred screaming fans, noticed that all the examples of the epitomized backstages we were listing off had had their heyday before we were even old enough to get into any of their shows. This was not what MTV (back when MTV, actually stood for Music Television) or even Vice Magazine had promised us backstage would be like when we grew up. It looked increasingly less like the photo above.

It looked a lot more like this:

Mike Gallagher of the band Isis, backstage at the Trocadero – Philadelphia, 2007 / Image: Markphoto.net

And that’s when it dawned on me: the Internet had killed the rock star.

Well, first off, is there anything the Internet hasn’t already killed yet? Back in May, The Atlantic featured a piece about the Internet’s ongoing assassination of the music industry — a crime story a decade old now, but, like the JonBenét Ramsey of disruptive technology, undyingly over-covered. Other casualties in the Internet’s Edward Gorey-like murder spree have included music journalism, killed by mp3 blogs, pirate radio, killed by general redundancy, and even the mystique of the radio star (which, hadn’t video already confessed to killing like 30 years prior?) killed by too much exposure. At this point, to say the Internet’s done away with anything else when it comes to music is, admittedly, a cliché, but, nevertheless, I do think there’s one more, less-publicized casualty.

In an interview with NME earlier this year, Kasabian singer Tom Meighan was on to part of it:

It’s not like what it used to be like in rock ‘n’ roll. In the ’60s and ’70s you had the likes of David Bowie and Marc Bolan, and then in the ’80s you even had shit acts that were rock stars.

I think – especially in the last three or four years – the internet’s taken a stranglehold and killed off the myth of the rock star now. You know when you used to buy the records and there was the myth behind them? There’s too much on blogs now and I think it’s killed it off. Nobody’s surprised by an interview anymore or anything. It’s quite tragic.

There are so many rock stars writing these self pitying blogs and it’s not in the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll, it’s like ‘Wow, what rubbish’.

That’s the victim no one talks about when they’re focusing instead on how much money the RIAA’s member organizations are losing due to the Internet: the “spirit of rock ‘n’ roll.” Cuz you know what those acts in the 60’s and 70’s and 80’s and, to a large extent, the 90’s didn’t have backstage? Email. Or Facebook or Twitter. There were no urgent texts that needed immediate replies, no forums of endless fan comments to be compulsively monitored, no hundreds of images from the previous night’s show to be sorted through and uploaded, no online profiles for potentially competing or collaborating artists to be stalked, no blog posts that needed to be written, or livestreams set up. Hell, there weren’t even any cell phones with which to call anyone during those hours and hours on the tour bus. Not to mention any of the normal things that even non-rock stars do on their computers, like instant message with their friends or watch the entire last season of Mad Men. Millennials — the generation whose older members are now of rock star age — spend almost 10 hours a day online. Add to that the three more hours per day that Americans now spend using the web on their mobile phones, and then factor in the completely-absurd-even-to-this-millennial FOUR THOUSAND texts that the average (AVERAGE!!) teenager sends per month — that’s six texts every waking hour — and all of that compounds into a LOT of time that the typical touring act in 2010 is spending doing shit that simply wasn’t there to have been done back in the day. Before we all developed these new digital compulsions there used to be a lot more time for, and a lot fewer pressing distractions from, the analog ones, namely the sex + drugs that = the “spirit of rock ‘n’ roll.”

Of course, being a rock star back in the 20th century, you could also get away with a lot more than you can now. Your drug-addled, sex-addicted, minor-fucking ways were not gonna end up on Twitter three seconds after some groupie snapped a photo on her cell phone, let alone on TMZ. To a large extent, truly rock star behavior used to be a lot easier to contain. Now, there’s really no buffer. And that increasingly permeable line cuts in both directions. Much as self-pitying blog posts are a definite cramp in the rock ‘n’ roll style, so is not being able to avoid your hate mail. In the past, your handlers would have simply made sure you never saw it. Now, not only does it take some herculean willpower to avoid the known hubs of haterade — and rock stars aren’t famous for their self-restraint — but even for the most disciplined musicians, messages letting you know you suck are like online porn: one in three of us has ended up with it in our face even when we weren’t looking for it. It’s why Trent Reznor quit Twitter last year…. Twice. The first time around, Reznor posted the following on the Nine Inch Nails forum by way of explanation:

When Twitter made it’s way to my radar…. I decided to lower the curtain a bit and let you see more of my personality. I watched some of you get more engaged because you started to realize there’s a person (flaws and all) back there, and I watched some of you recoil in horror because I’m not what you projected on me. All expected. I’m not as concerned about “breaking” your idea of NIN at this point. It is what it is and I am what I am. The relationship between artist and fan is changing if you haven’t noticed, along with the way we consume and experience music and even communicate since the internet arrived.

….But some people exist to ruin it for others – and they are the ones who have nothing better to do with their time. Example: on nin.com, there’s 3-4 different people that each send me between 50 – 100 message per day of delusional, often threatening nonsense. We can delete them, but they just sign back up and start again. Yes, we are implementing several changes to address this, but the point is it quickly gets very old weeding through that stuff.

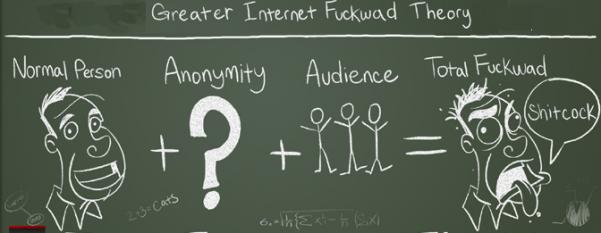

Rock ‘n’ roll has never been scared of confrontation, but in the past it’s always been in-person, and visceral. Being able to settle things with a fistfight or a blunt and / or glass object is incredibly more rock ‘n’ roll-y than this new equation:

Image: John Gabriel

Of course, it’s undeniable there are significant advantages that all this new technology has afforded artists as well. From those just starting out to the ones with Stadium Status, the Internet has put a lot of new tools and resources directly into artists’ hands, allowing them unprecedented control over their own careers and their relationship with their fans. But it also means that handling much of what a label was once responsible for — and even more that they still haven’t even figured out how to do — is now part of the job requirement of being a successful musician. You have to be an expert in marketing, branding, community strategy, and user engagement; knowing how to write code, the meaning of the term “information architecture,” and a good web designer also help. “Engaging your fans” the old fashioned way meant spraying them with champagne in the green room. Now, replying to messages on Facebook is your second job. A couple of decades ago you wouldn’t have had to be giving a shit about anything called a website; now you have to anticipate you’ll be redoing yours every few years just to keep up with the rapid pace of change on the web. A friend of mine who’s in a band that just finished a tour of the U.S. followed by Australia, told me in the wake of the band’s website redesign to incorporate the StageBloc platform, a process that spanned several months, “At the time, I didn’t think that working at an internet startup was going to be helpful to my music career.” Which also speaks to the kind of personality the evolution of rock ‘n’ roll is selecting for these days.

Think about the best concert you’ve seen in the past five years. You know what the band did after the show? They checked a bunch of email, sent a bunch of texts, possibly also a bunch of Tweets, and generally stared at screens for a while. Cracked.com’s list of the 7 Most Impossible Rock Stars to Deal With, which features the likes of DMX, Keith Moon, Iggy Pop, Nikki Sixx, Ozzy Osbourne, and Eric Clapton — all people who were wreaking havoc by the time they were my age — includes absolutely no one who is my age now. (And aren’t we, Millennials, supposed to be the over-entitled spoiled-brat “Generation Me”?) While the barrier to entry into rockstarhood may have never been as porous (getting discovered on YouTube, anyone?), the competition has arguably never been more intense. Just being a talented performer and charismatic entertainer is not enough anymore. The same tools that are giving artists more control are also saddling them with more responsibility. The business savvy and marketing aptitude that once made Madonna an anomalous success are now prerequisite just to stay in the game. You simply couldn’t keep up if you are the kind of mess that the emblematic rock stars who defined the term got to be. Or, perhaps, as Cracked suggests, all the drug addiction and general nihilism were so rampant among rock stars in the olden days “possibly because no one had invented the Internet yet, [and] they got bored.”

Of course, there’s still bands like Justice, whose trouble-making, euro-hipster decadence is entertaining enough for an hour-long tour documentary. But as you’ll realize if you watch the “A Cross The Universe” DVD, chronicling the band’s 2008 U.S. tour, the duo hardly spend time at their computers, aside from when they’re performing. And there’s no mystery why. The band doesn’t have a website, or Twitter. Their Facebook is a UGC Community Page created by fans. They basically just have a Myspace, which is maintained by their French label, Ed Banger Records. In a sense, Justice isn’t so much an exception as an appropriately ironic throwback. The documentary, hearkening back to when rock stars were legitimately so, effectively paints the laptop rocker duo in those nostalgically familiar colors.

When asked during the promo tour for his latest book, Imperial Bedrooms, whether contemporary book launches are more or less fun than when he started in the late 80’s, Bret Easton Ellis — arguably the closest equivalent that the literary world has to a rock star, and a writer who has expertly articulated the unbridled excess that is the trope’s defining characteristic (“It was always the A booth. It was always the front seat of the roller coaster. It was never ‘Let’s not get the bottle of Cristal’ … It was the beginning of a time when it was almost as if the novel itself didn’t matter anymore—publishing a shiny booklike object was simply an excuse for parties and glamour.”) — laughed, “Oh, it’s less fun. It’s much less fun. Because we’re in the ‘post-Empire’ world now. Book publishing,” he added, “flourished in the ‘Empire,'” a term which Ellis uses to refer to the period from 1945 until 2005 — the era that defined the 20th century, and a time when, not coincidentally, the rock star flourished, too.

There’s a reason that Aldous Snow — the rock ‘n’ roll MacGuffin played by Russell Brand in this summer’s Get Him To The Greek, the latest installment “From the Director of Forgetting Sarah Marshall and the Producer of Knocked Up and Superbad” — is referred to in the movie as “one of the last remaining rock stars.” When it comes to this 20th century Dionysian archetype, there really aren’t that many left. The Internet is making sure of it.