.

I design healthcare experiences for a living. This includes:

- Designing experiences for patients

- Designing experiences that facilitate the relationship between providers and their patients

- Designing solutions for leveraging large swathes of medical data to improve health outcomes at population scale

A lot of work is being done to bring design thinking to healthcare. I’d like to explore how healthcare can be a source for design philosophy. Not because healthcare has experience design figured out — not by a long shot, obviously. As an industry, healthcare is often rife with misaligned, and even malign incentives that can lead to awful results. But as a discipline of diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, healthcare is the endeavor of healing. The applications of healing — physical, mental, psychological— are themselves technologies. And I believe the technology of healing can offer a novel perspective to reexamine how we think about broader technology design.

.

Design is about choices.

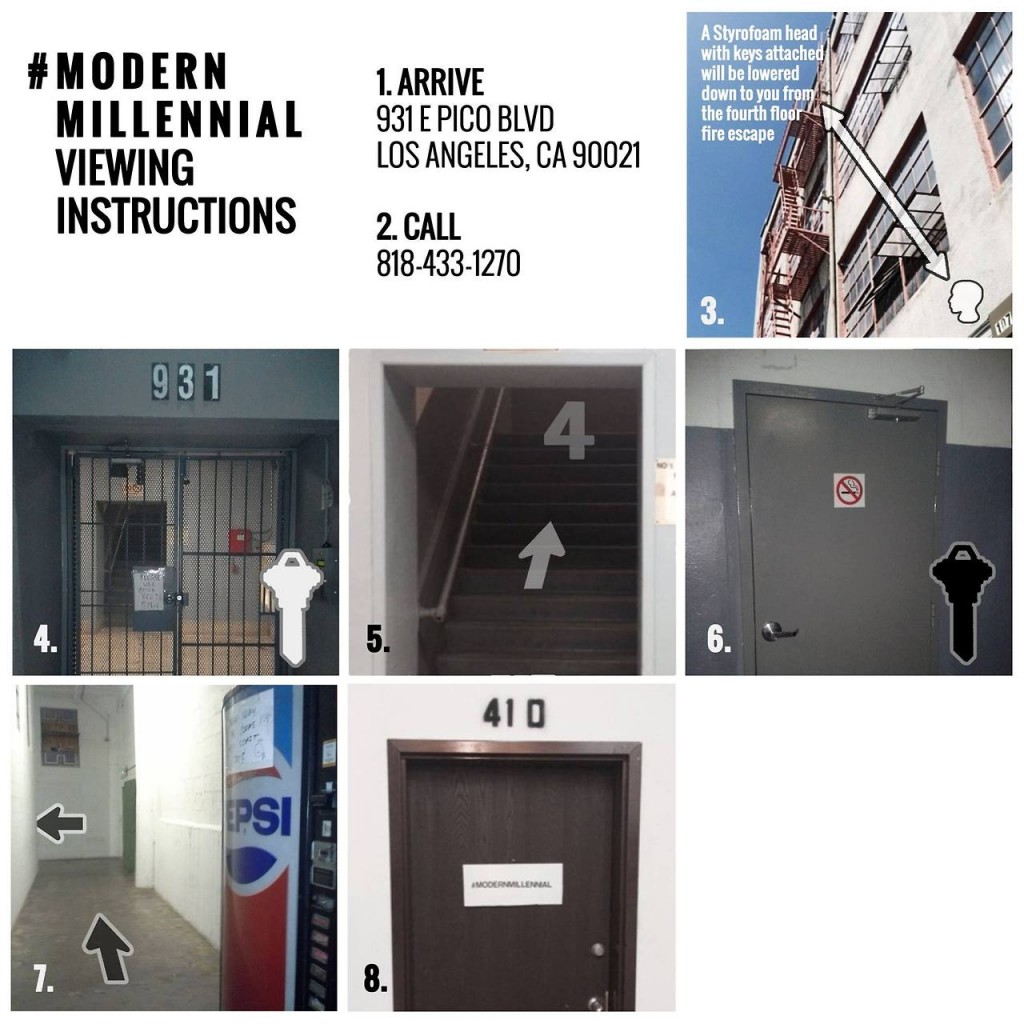

Earlier this year, The Center for Humane Technology, an organization founded by former Google Design Ethicist, Tristan Harris, to “align technology with humanity’s best interests,” partnered with Moment, an app that helps people track their screen time, to find out how people feel after using different apps. They collected data from 200,000 iPhone users and ranked the apps that made people feel the happiest, and the ones that made them most regret the time they’d spent there.

What’s interesting about what their findings reveal is that four of the top ten apps that make people feel happiest about having used them are designed specifically to facilitate mental / physical health practices.

Source: Center for Humane Technology

Source: Center for Humane Technology

Zero of the top 15 apps that make people most unhappy are.

. . .

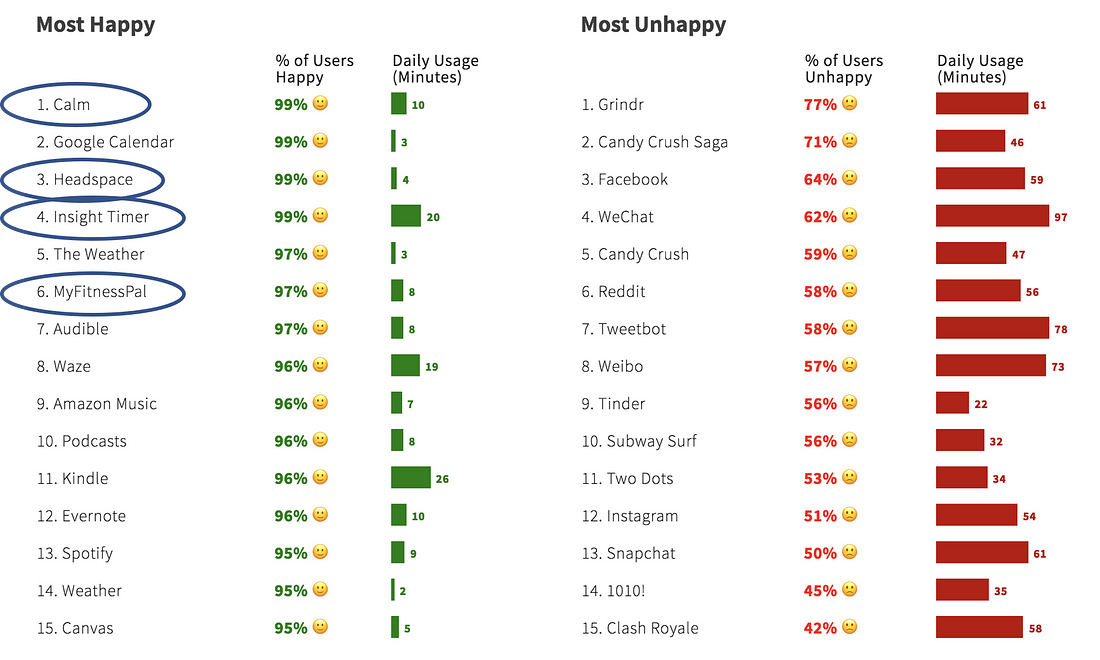

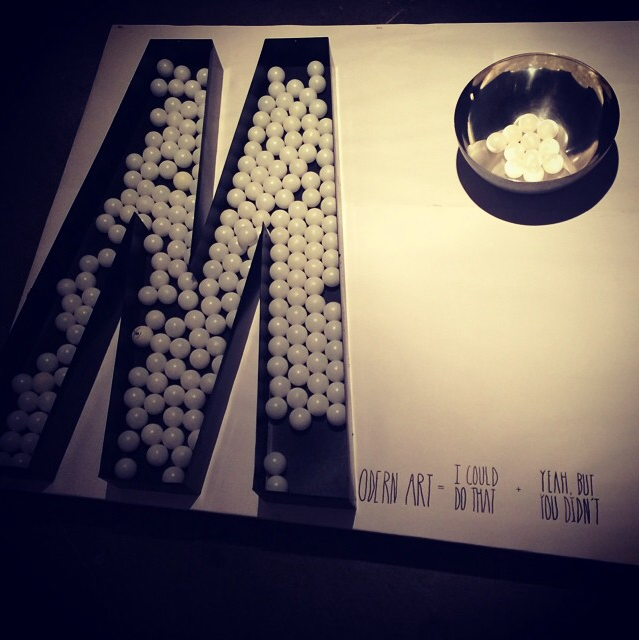

The history of technology design has traditionally been about the application of persuasion practices — exploiting humans’ cognitive and psychological vulnerabilities to influence their behavior.

Here is just a sampling of the product design canon that has ended up on my own bookshelf:

Persuasive design has provided the educational foundation for technology creators and its essentially unquestioned (until recently) behavioralist philosophy has wound up directly embedded into the products they develop. Products that have gone on to affect how billions of people now experience their lives. At an existential level technology remakes culture: the philosophy that proliferates through the products we use in turn defines the values we absorb, the behaviors we adopt, and the social norms we internalize by using them. But in a very practical sense, persuasive design philosophy has simply provided a framework for defining which design choices are considered valuable, and which are not.

Healing offers a different modality through which to evaluate design choices, and expands the spectrum of available options for those choices.

What can we learn from healing technologies, both timeless and cutting edge, to inform a design philosophy for the kinds of products people are happy to have in their lives?

.

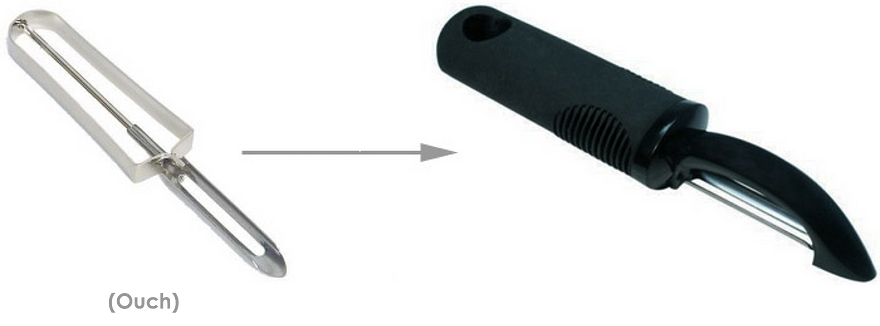

1. Pain Reduction (vs. “delight”)

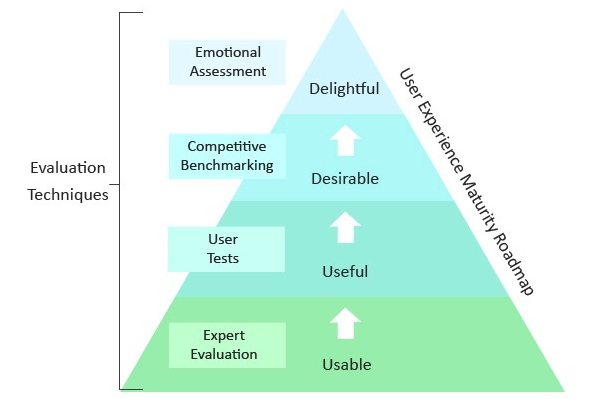

“The quality of emotional responses elicited by a product is a measure of its delightfulness,” according to UX Magazine. “Delightful is the highest level of UX maturity.”

Source: UX Magazine “UX Maturity Model”

Source: UX Magazine “UX Maturity Model”

But is it?

What if, as Erika Hall suggests, “Creating ‘delightful’ user experiences is actually “user-hostile when it wrongly presumes that your customer wants to be emotionally involved with your service at all.”

Put another way:

“Fast and invisible are often the better parts of delight,” Hall adds.

In other words, pain reduction can be more valuable — and pleasurable — than emotional engagement with a designed experience.

Rather than thinking about how we can more delightfully coerce people into doing something, how do we instead design to take away the pain standing in their way?

.

2. Connectedness (vs. “contacts”)

A 2015 study out of Carnegie Mellon found that participants with a strong sense of social support developed less severe symptoms when exposed to the common cold than those who felt socially deprived. A 2010 study examining over 300,000 people around the world found that low levels of social support posed a premature death risk comparable to smoking and alcohol consumption. The World Health Organization has even identified social support networks as a primary determinant of health.

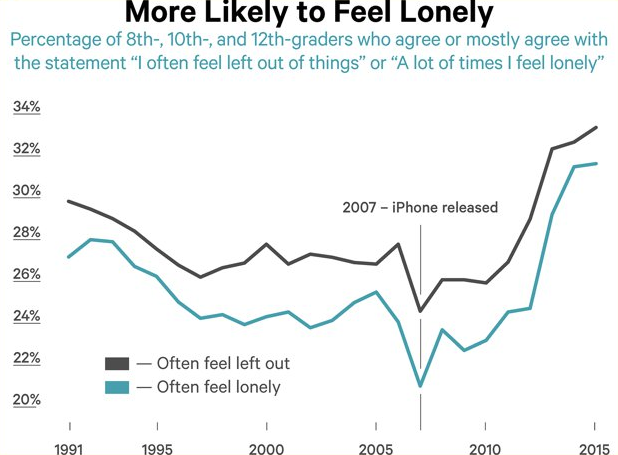

And yet, more than one-third of Americans over the age of 45 report feeling lonely. The prevalence of loneliness is especially high among those over 65 and under 25. Looking at high school students’ feelings of loneliness tracked since the 1990s, an interesting inflection point stands out:

Source: Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?

Source: Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?

The uptick in teen loneliness begins immediately after the release of the iPhone.

“We live in the most technologically connected age in the history of civilization,” writes former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, “yet rates of loneliness have doubled since the 1980s.”

How is it that our unprecedented social technologies have exacerbated our feelings of alienation?

While a growing body of evidence is revealing the health benefits of meaningful connectedness, design choices have been made to dope us into a haze of superficial “contacts” — weak ties and surface interactions.

Image source: How Technology is Hijacking Your Mind — from a Magician and Google Design Ethicist

Image source: How Technology is Hijacking Your Mind — from a Magician and Google Design Ethicist

Considering the impact that meaningful connectedness has on our health, how do we design for experiences that facilitate it?

.

3. Precision Medicine (vs. “happy path”)

Precision medicine is an emerging medical discipline of tailoring customized treatment and prevention approaches based on a patient’s specific genetic information and environment.

Advertising technology and feed filter algorithms have already scaled precision-targeting to create personalized, alternative media realities. But product design is still largely reliant on the starting point of a default workflow — a “happy path.”

Yet the happy path can not only fail users but actually create suffering.

As Eric Meyer wrote in 2014:

I didn’t go looking for grief this afternoon, but it found me anyway. And I have designers and programmers to thank for it. In this case, the designers and programmers are somewhere at Facebook.

“Eric, here’s what your year looked like!”

A picture of my daughter, who is dead. Who died this year.

Yes, my year looked like that. True enough. My year looked like the now-absent face of my little girl. It was still unkind to remind me so forcefully.

The design is for the ideal user, the happy, upbeat, good-life user. In creating this Year in Review app, there wasn’t enough thought given to cases like mine, or anyone who had a bad year. If I could fix one thing about our industry, just one thing, it would be that: to increase awareness of and consideration for the failure modes, the edge cases, the worst-case scenarios.

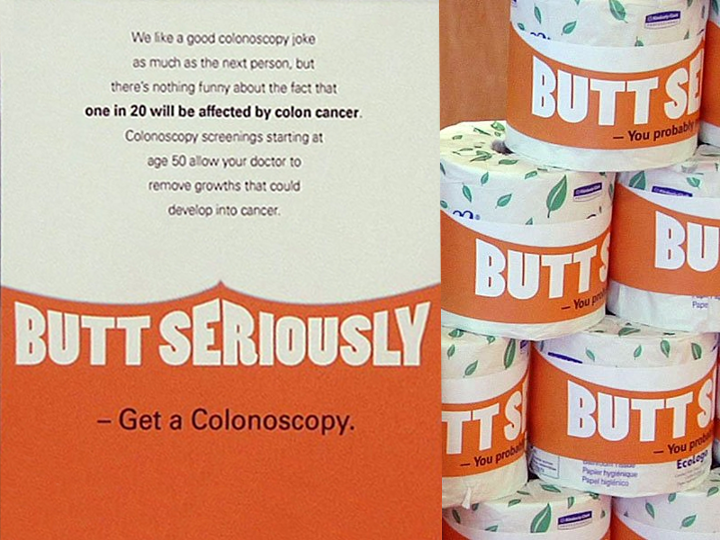

The precision medicine concept applied to design could mean avoiding this kind of UX cruelty.

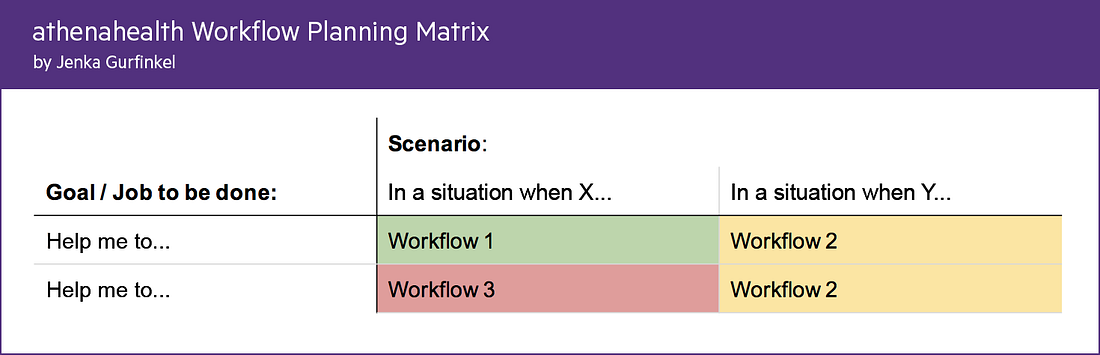

In healthcare, “edge cases” can still have implications for millions of people. To help simplify the complexity of designing for an environment like this I developed a workflow planning tool at athenahealth. The goal is to easily document and account for the various situations in which users may find themselves.

Understanding the implications of distinct workflows on their own terms, rather than as deviations from a default, makes it easier to step away from the mental model of a “happy path” and design for a more inclusive range of real-life user scenarios.

How else can precision medicine thinking allow product designers to reframe “edge cases” and “outlier” scenarios and find scalable approaches for addressing the needs of diverse users?

.

4. Population Health (vs. “engagement”)

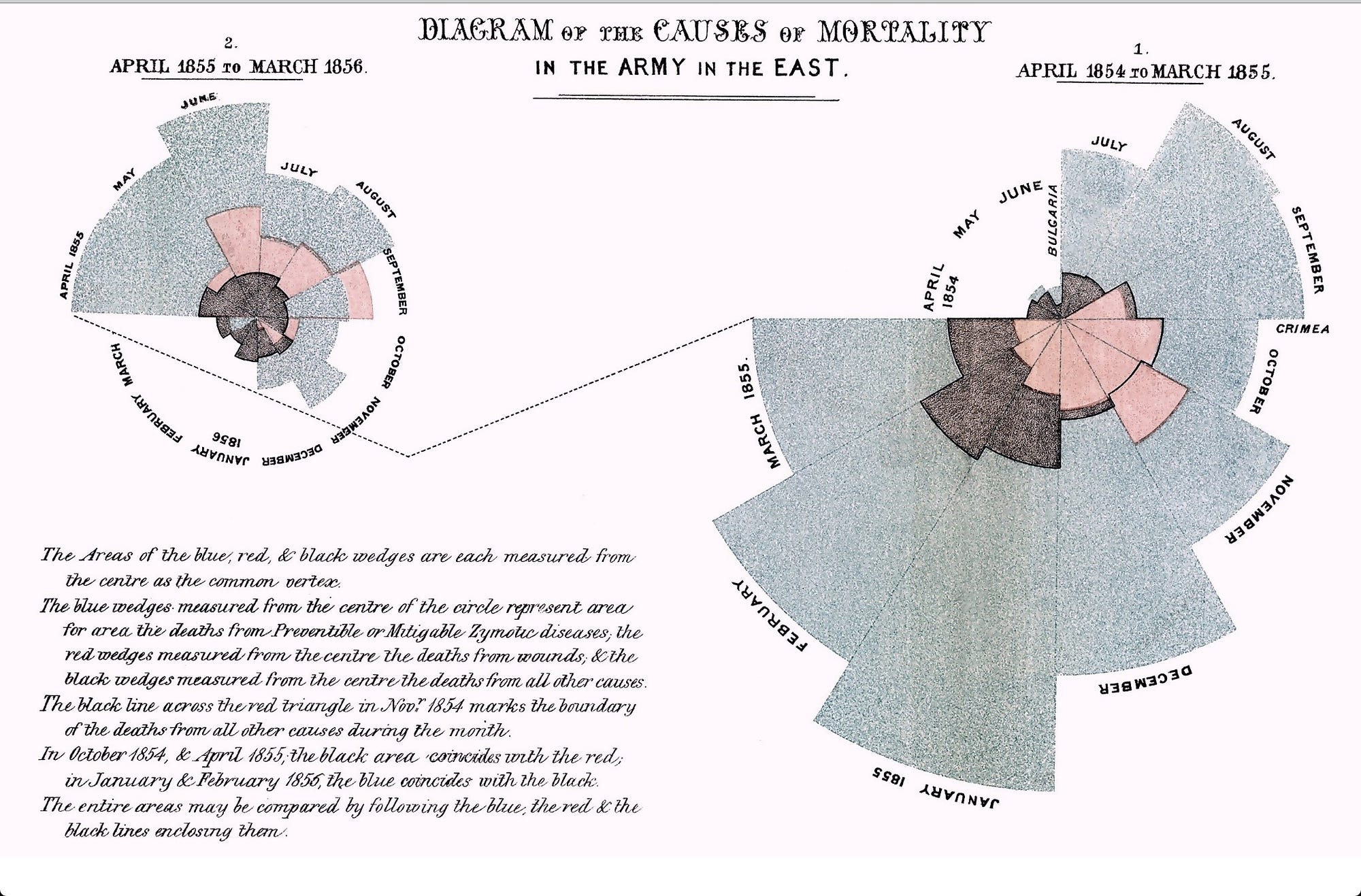

Population Health is an approach to healthcare that is based on evaluating health outcomes at population scale, and driving informed clinical decisions to improve those outcomes. The sheer amount of data we now have available and the tools with which we can wield it make population health a hot new area for healthcare, but Florence Nightingale was using these same methods out on nineteenth century, Crimean battlefields to assess causes of preventable deaths among soldiers:

You can’t optimize for what you don’t measure. So what ARE we measuring?

Clicks. Likes. Shares. Comments… Engagements. Often, simply whatever is the most obvious event metric to record and track — not necessarily the most salient or meaningful.

How happy are our users after using our product? How is their well-being affected? How much less pain and more meaningfulness have we contributed?

“Metrics,” Niels Hoven writes, “are leading indicators, not end goals. One of my favorite stories is from a friend who worked on improving the search feature at a major tech company. Their target metric was to increase the number of searches per user, and the most efficient way to do that was to make search results worse. My friend likes to think that his team resisted that temptation, but you can never be totally sure of these things.”

Metrics are, as Hoven adds, “just heuristics, actionable proxies that could be measured on a short time scale” They are not sufficient “stand-ins for long-term product health.”

Nor, for that matter, for the long term health of our user population.

We have been very busy measuring, and optimizing for engagement / user actions. How do we measure the health of our user populations in order to achieve better quality outcomes?

. . .

UX RX

Y-Combinator, the famous startup incubator that has helped create successes like AirBnB, DropBox, Instacart, Reddit, and more, has a motto:

And the thing is….people WANT less pain, they want more connectedness, and better health! These are not things people DON’T want. They’re just often not what’s being designed for.

Taking a cue from Harris’s years of work on the Time Well Spent movement, earlier this year Mark Zuckerberg announced his intent to shift Facebook’s product directive towards “encouraging the most meaningful social interactions.” He wanted Facebook to become “more focused on trying to measure and have people tell us what is creating the most meaningful interactions in their lives. Not just on Facebook. It could be a message that you have on Messenger or WhatsApp, but it could also be that you see something on Facebook and have a conversation about that in the world with someone who’s meaningful to you, and that’s something that we need to understand.”

Looking to the technology of healing as a source of design philosophy isn’t about sacrificing commercial viability. It’s about employing a different framing for what people want, and a different way of thinking about our priorities in the way we design the products that shape people’s lives.

@babiejenks

@babiejenks

@babiejenks

@babiejenks