By maximizing efficiency, technology has transformed dating into a routine for the acquisition of sex. Love has been, literally, written out of the code for a generation afraid to catch feelings.

.

.

.

Death.

The future, as per usual, arrived first in Japan.

Last year fewer babies were born in Japan than any year on record. Roughly 1.001 million babies were born, and 1.269 million people died, leaving the country with 268,000 fewer people. In U.S. terms, that’s like if everyone in Newark up and disappeared last year. 2014 was just the latest record-breaking drop in a sharp, downward trajectory that began pretty much exactly 40 years ago.

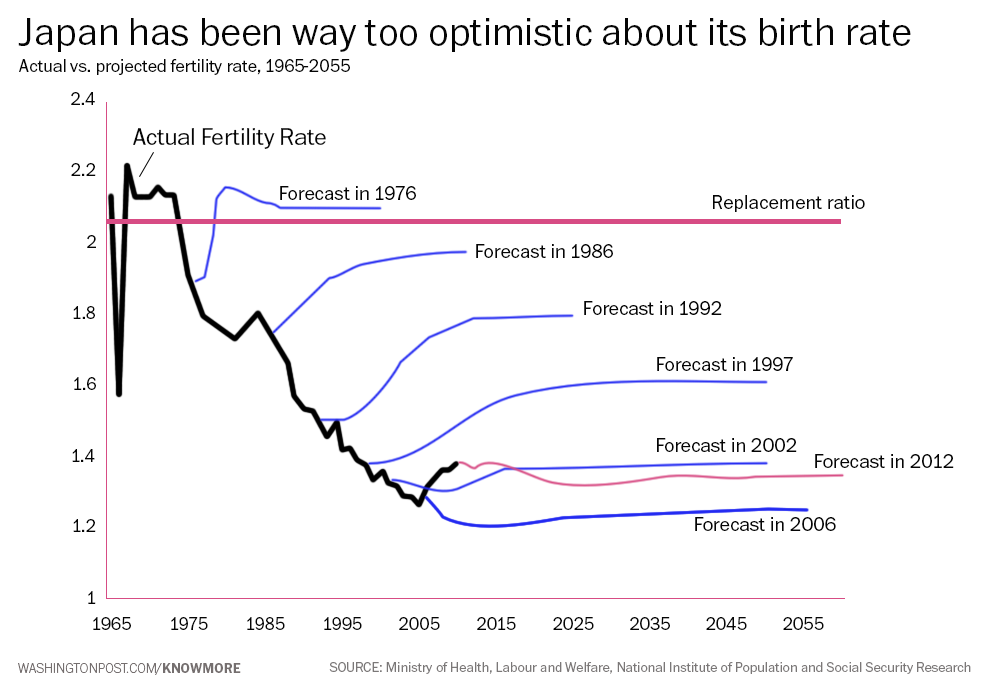

For decades, the Japanese Government kept misinterpreting this negative population growth as a temporary dip rather than an sustained trend. The Washington Post created a graph based on the data from a 2014 working paper from Tokyo’s Waseda University, showing the government projections compared against reality —

— an eerie EKG of a dying body being repeatedly defibrillated with mounting futility and desperation.

In 2013, the year adult incontinence diapers outsold baby diapers in Japan for the first time, Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research released a projection that, based on current trends, by 2060 30% of Japanese people will be gone.

Birth rates are declining across the developed world, but exactly what kind of Children of Men style apocalypse is going on in Japan?

“Japan’s under-40s appear to be losing interest in conventional relationships,” Abigail Haworth wrote in The Guardian. “Millions aren’t even dating, and increasing numbers can’t be bothered with sex. For their government, “celibacy syndrome” [sekkusu shinai shokogun] is part of a looming national catastrophe:

A survey in 2011 found that 61% of unmarried men and 49% of women aged 18–34 were not in any kind of romantic relationship, a rise of almost 10% from five years earlier. Another study found that a third of people under 30 had never dated at all. A survey earlier this year by the Japan Family Planning Association (JFPA) found that 45% of women aged 16–24 “were not interested in or despised sexual contact.” More than a quarter of men felt the same way. Japan’s Institute of Population and Social Security reports an astonishing 90% of young women believe that staying single is “preferable to what they imagine marriage to be like.”

“Both men and women say to me they don’t see the point of love,” says Ai Aoyama [a sex and relationship counsellor, and former professional dominatrix]. “They don’t believe it can lead anywhere.”

“Mendokusai.”

Mendokusai translates loosely as “Too troublesome” or “I can’t be bothered.” It’s the word I hear both sexes use most often when they talk about their relationship phobia. Romantic commitment seems to represent burden and drudgery. “I find some of my female friends attractive,” says Satoru Kishino, 31 “But I’ve learned to live without sex. Emotional entanglements are too complicated. I can’t be bothered.”

Eri Asada, 22, who studied economics, has no interest in love. “I gave up dating three years ago. I don’t miss boyfriends or sex. I don’t even like holding hands.”

“Gradually but relentlessly, Japan is evolving into a type of society whose contours and workings have only been contemplated in science fiction,” Demographer Nicholas Eberstadt wrote last year.

[But] aversion to marriage and intimacy in modern life is not unique to Japan. Many of the shifts there are occurring in other advanced nations, too. Is Japan providing a glimpse of all our futures?

.

Sex.

“It’s a balmy night in Manhattan’s financial district,” writes Nancy Jo Sales in Vanity Fair, “And at a sports bar called Stout, everyone is Tindering. The tables are filled with young women and men who’ve been chasing money and deals on Wall Street all day, and now they’re out looking for hookups. Everyone is drinking, peering into their screens and swiping on the faces of strangers they may have sex with later that evening.”

Sales captures an essential ethnography of a world — told mostly through the words of its inhabitants themselves — where “an unprecedented phenomenon is taking place, in the realm of sex” as hookup culture collides with dating apps:

At a booth in the back, three handsome twentysomething guys in button-downs are having beers. They are Dan, Alex, and Marty, budding investment bankers at the same financial firm, which recruited Alex and Marty straight from an Ivy League campus. When asked if they’ve been arranging dates on the apps they’ve been swiping at, all say not one date, but two or three: “You can’t be stuck in one lane … There’s always something better.” “If you had a reservation somewhere and then a table at Per Se opened up, you’d want to go there,” Alex offers.

“Guys view everything as a competition. Who’s slept with the best, hottest girls?” With these dating apps, he says, “you’re always sort of prowling. You could talk to two or three girls at a bar and pick the best one, or you can swipe a couple hundred people a day — the sample size is so much larger. It’s setting up two or three Tinder dates a week and, chances are, sleeping with all of them, so you could rack up 100 girls you’ve slept with in a year.”

He says that he himself has slept with five different women he met on Tinder in the last eight days. Dan and Marty, also Alex’s roommates, can vouch for that. In fact, they can remember whom Alex has slept with in the past week more readily than he can.“Brittany, Morgan, Amber,” Marty says, counting on his fingers. “Oh, and the Russian — Ukrainian?”

“Ukrainian,” Alex confirms.

“I hooked up with three girls, thanks to the Internet, off of Tinder, in the course of four nights, and I spent a total of $80 on all three girls,” Nick relays proudly. He goes on to describe each date, one of which he says began with the young woman asking him on Tinder to “‘come over and smoke [weed] and watch a movie.’ I know what that means,” he says, grinning.

In his iPhone, has a list of more than 40 girls he has “had relations with, rated by [one to five] stars…. It empowers them,” he jokes. “It’s a mix of how good they are in bed and how attractive they are.”

They laugh.

.

Of the themes that emerge from Sales’ piece, one is efficiency:

At a table in the front, six young women have met up for an after-work drink. They’re seniors from Boston College, all in New York for summer internships. None of them are in relationships, they say.

“New York guys, from our experience, they’re not really looking for girlfriends,” says the blonde named Reese. “They’re just looking for hit-it-and-quit-it on Tinder. They start out with ‘Send me nudes.’ Or they say something like ‘I’m looking for something quick within the next 10 or 20 minutes — are you available?’ ‘O.K., you’re a mile away, tell me your location.’ It’s straight efficiency.”

“I’m on Tinder, Happn, Hinge, OkCupid,” Nick says. “It’s just a numbers game. Before, I could go out to a bar and talk to one girl, but now I can sit home on Tinder and talk to 15 girls — ”

“Without spending any money,” John chimes in.

“I’ve gotten numbers on Tinder just by sending emojis,” says John. “Without actually having a conversation — having a conversation via emojis.”

He holds up his phone, with its cracked screen, to show a Tinder conversation between him and a young woman who provided her number after he offered a series of emojis, including the ones for pizza and beer.“

“Now is that the kind of woman I potentially want to marry?” he asks, smiling. “Probably not.”

Neither Nick nor John has had a girlfriend in the last few years; Brian had one until recently but confesses, “I cheated…. She found out by looking at my phone — rookie mistake, not deleting everything.”

They all say they don’t want to be in relationships. “I don’t want one,” says Nick. “I don’t want to have to deal with all that — stuff.”

“You can’t be selfish in a relationship,” Brian says. “It feels good just to do what I want.”

I ask them if it ever feels like they lack a deeper connection with someone.

There’s a small silence. After a moment, John says, “I think at some points it does.”

“But that’s assuming that that’s something that I want, which I don’t,” Nick says, a trifle annoyed. “Does that mean that my life is lacking something? I’m perfectly happy. I have a good time. I go to work — I’m busy. And when I’m not, I go out with my friends.”

“Or you meet someone on Tinder,” offers John.

“Exactly,” Nick says. “Tinder is fast and easy, boom-boom-boom, swipe.”

Another theme is intimacy:

Asked what these women are like, he shrugs. “I could offer a résumé, but that’s about it … Works at J. Crew; senior at Parsons; junior at Pace; works in finance …”

“We don’t know what the girls are like,” Marty says.

“And they don’t know us,” says Alex.

Marty, who prefers Hinge to Tinder (“Hinge is my thing”), says he’s slept with 30 to 40 women in the last year: “I sort of play that I could be a boyfriend kind of guy,” in order to win them over, “but then they start wanting me to care more … and I just don’t.”

“Dude, that’s not cool,” Alex chides. “I always make a point of disclosing I’m not looking for anything serious. I just wanna hang out, be friends, see what happens … If I were ever in a court of law I could point to the transcript.” But something about the whole scenario seems to bother him. “I think to an extent it is, like, sinister,” he says.

“When it’s so easy, when it’s so available to you,” Brian says intensely, “and you can meet somebody and fuck them in 20 minutes, it’s very hard to contain yourself.”

“It’s rare for a woman of our generation to meet a man who treats her like a priority instead of an option,” wrote Erica Gordon on the Gen Y Web site Elite Daily, in 2014.

“I had sex with a guy and he ignored me as I got dressed and I saw he was back on Tinder.”

It is the very abundance of options provided by online dating which may be making men less inclined to treat any particular woman as a “priority,” according to David Buss, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin who specializes in the evolution of human sexuality. “Apps like Tinder and OkCupid give people the impression that there are thousands or millions of potential mates out there,” Buss says. “One dimension of this is the impact it has on men’s psychology. When there is a surplus of women, or a perceived surplus of women, the whole mating system tends to shift. Men don’t have to commit, so they pursue a short-term mating strategy. Men are making that shift, and women are forced to go along with it in order to mate at all.”

Bring all of this up to young men, however, and they scoff. Women are just as responsible for “the shit show that dating has become,” according to one. “Romance is completely dead, and it’s the girls’ fault,” says Alex, 25, a New Yorker who works in the film industry.

“They act like all they want is to have sex with you and then they yell at you for not wanting to have a relationship. How are you gonna feel romantic about a girl like that? Oh, and by the way? I met you on Tinder.”

“Women do exactly the same things guys do,” said Matt, 26, who works in a New York art gallery. “I’ve had girls sleep with me off OkCupid and then just ghost me” — that is, disappear, in a digital sense, not returning texts. “They play the game the exact same way. They have a bunch of people going at the same time — they’re fielding their options. They’re always looking for somebody better, who has a better job or more money.” A few young women admitted to me that they use dating apps as a way to get free meals. “I call it Tinder food stamps,” one said.

And pleasure?

“What’s a real orgasm like,” says Courtney with a sigh. “I wouldn’t know. A lot of guys are lacking in that department.”

They all laugh knowingly.

“I know how to give one to myself,” says Courtney.

“Yeah, but men don’t know what to do,” says Jessica, texting.

“Without [a vibrator] I can’t have one,” Courtney says. “It’s never happened” with a guy. “It’s a huge problem.”

“It is a problem,” Jessica concurs.

According to multiple studies, women are more likely to have orgasms in the context of relationships than in uncommitted encounters. More than twice as likely, according to a study done by researchers at the Kinsey Institute and Binghamton University.

They talk about how it’s not uncommon for their hookups to lose their erections. It’s a curious medical phenomenon, the increased erectile dysfunction in young males, which has been attributed to everything from chemicals in processed foods to the lack of intimacy in hookup sex.

“I think men have a skewed view of the reality of sex through porn,” Jessica says, looking up from her phone. “Because sometimes I think porn sex is not always great — like pounding someone.” She makes a pounding motion with her hand, looking indignant.

“Yeah, it looks like it hurts,” Danielle says.

“Like porn sex,” says Jessica, “those women — that’s not, like, enjoyable, like having their hair pulled or being choked or slammed. I mean, whatever you’re into, but men just think” — bro voice — “ ‘I’m gonna fuck her,’ and sometimes that’s not great.”

“Yeah,” Danielle agrees. “Like last night I was having sex with this guy, and I’m a very submissive person — like, not aggressive at all — and this boy that came over last night, he was hurting me.”

They were quiet a moment.

Tech.

“There have been two major transitions” in heterosexual mating “in the last four million years,” says Justin Garcia, a research scientist at Indiana University’s Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, quoted in Sales’ article. “The first was around 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, in the agricultural revolution, when we became less migratory and more settled,” leading to the establishment of marriage as a cultural contract. “And the second major transition is with the rise of the Internet. It’s changing so much about the way we act both romantically and sexually.”

In February, 2015, Sales writes, “one study reported there were nearly 100 million people — perhaps 50 million on Tinder alone — using their phones as a sort of all-day, every-day, handheld singles club, where they might find a sex partner as easily as they’d find a cheap flight to Florida.”

“It is unprecedented from an evolutionary standpoint,” Garcia says. We are in “uncharted territory.”

But out here on the drought-ravaged, California desert frontier that’s spawned the iPhone and Tinder (not to mention Snapchat, Twitter, Instagram, Google, Facebook, etc., etc.), the humans creating the technology are drawing the maps.

In the Berkeley Journal of Sociology article, Morality and the Idea of Progress in Silicon Valley, Eric Gianella writes, “We’d like to be able to claim that making things more [efficient] is good. This justifies the countless products and services whose origins can be traced to someone noticing an opportunity for optimization. But there are many cases in which we need to question whether making activities more [efficient] is moral.”

And when it comes to romance, is efficiency even what we want?

I mean, if we do, we’re in luck. The Japanese have already figured out how to take that impulse to its ultimate conclusion. (Of course).

“In Japan today there’s a whole industry of relationship replacement services,” Ryan Duffy explained, in Vice’s 2013 travelogue through Japan’s Love Industry, “You can essentially replicate anything you’d get from a relationship, be it sexual, emotional, or otherwise, without actually having to have a boyfriend or girlfriend.” From the now globally famous Japanese host bars, where professionals simulate the companionship experience of a date (strictly conversation, not copulation) as-a-service — “Women are willing to affix a price for the experience,” a host who makes $800,000 a year casually explains, “It’s totally normal,” — to platonic “cuddle cafes,” where customers can order off a menu of services that includes getting to pet the cuddle hostess’s head, and gazing deeply into each others’ eyes for $80.

“Do you have a boyfriend?” Duffy asks Sakura Serizawa, his cuddle hostess, as he lies next to her, resting his head on her arm.

“Of course not,” she says, “Mendokusai. When I see happy couples during Christmas, I wish they would die. I don’t like seeing people being affectionate in public.”

“That’s interesting,” Duffy says, quietly horrified, “For someone who is affectionate with strangers for a living.”

“I have no emotional attachment to my customers,” Serizawa explains tonelessly, her artificially enlarged, anime-lensed eyes far away and hollow — like guacamole at Chipotle, eye contact with a human being in the land of efficiency costs extra.

“Nothing is weirder than this,” Duffy murmurs. “Profoundly, profoundly disturbing. We should stop this because it’s freaking me out.”

In voice-over Duffy later added, “I’ve seen a lot of perverse things in my life, but this pseudo-romance actually really got to me,” before culminating the Vice travel guide to Japan’s Love Industry at a Tokyo Hilton where a prostitute defecates in a bathtub and eats her own shit as a sexual service.

What the Japanese have realized is that why stop at sex? Every aspect of human contact can be commodified. Interaction without connection. What could be more efficient?

For Americans, that kind of streamlined optimization looks like this:

“Sex has become so easy,” says John, 26, a marketing executive quoted in Sales’ article. “I can go on my phone right now and no doubt I can find someone I can have sex with this evening, probably before midnight.”

“It’s like ordering Seamless,” says Dan, the investment banker, referring to the online food-delivery service. “But you’re ordering a person.”

But there’s a sense of absence in this paradise of frictionless efficiency. Some essential element’s gone missing in an invisible drought.

“When asked if there was anything about dating apps the young men I talked to didn’t like,” Sales writes, “’Too easy,’ ‘Too easy,’ ‘Too easy,’ I heard again and again.”

By reducing people to one-time-use bodies and sex to an on-demand exchange, dating apps have made what they yield us disposable and cheap. (Even Tinder is uneasy about its role in society being an orifice delivery service, disavowing it contributes to the very hookup culture its technology has not only branded but mainstreamed.)

“I call it the Dating Apocalypse,” a 29 year old New York woman tells Sales.

Or, in the vernacular of Silicon Valley: We have succeeded in disrupting love.

Enterprise Bridge, Lake Oroville, California

. .

Love.

If there’s one place where love is not dead, it’s the lab.

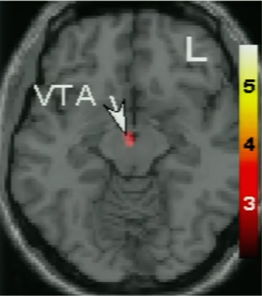

Anthropologist, Helen Fisher, and neuroscientist, Lucy Brown have been putting people who are madly in love into functional MRI brain scanners to find out what is going on up there, and they can tell you exactly where love lives in the brain:

This is your brain on love.

. .

[In] our study we found activity in a tiny, little factory near the base of the brain called the ventral tegmental area. We found activity in some cells called the A10 cells, cells that actually make dopamine, a natural stimulant, and spray it to many brain regions. Indeed, this part, the VTA, is part of the brain’s reward system. It’s way below your cognitive thinking process. It’s part of what we call the reptilian core of the brain, associated with wanting, with motivation, with focus and with craving. In fact, the same brain region where we found activity becomes active also when you feel the rush of cocaine.

There’s a very specific group of things that happen when you fall in love, and indeed, it has all of the characteristics of addiction. The first thing that happens is a person begins to take on what I call, “special meaning.” You focus on the person, you obsessively think about them, you crave them, you distort reality, your willingness to take enormous risks to win this person. It’s an obsession. As a truck driver once said to me, “The world had a new center, and that center was Mary Anne.”

In another lab, at Stony Brook University, the psychologist Arthur Aron and his colleagues succeeded in making two strangers fall in love as part of an experiment. The researchers wanted to know if they could create conditions that would make strangers quickly bond and form close friendships, even romantic relationships. They paired up random participants, seated them face to face, and gave them a sequence of 36 increasingly personal questions to ask one another and answer openly over an hour, including:

- Given the choice of anyone in the world, whom would you want as a dinner guest?

- What is the greatest accomplishment of your life?

- What do you value most in a friendship?

- Would you be willing to have horrible nightmares for a year if you would be rewarded with extraordinary wealth?

- While on a trip to another city, your spouse (or lover) meets and spends a night w/ an exciting stranger. Given they will never meet again, and you will not otherwise learn of the incident, would you want your partner to tell you about it?

- What foreign country would you most like to visit? What attracts you to this place?

Even before the hour was up, participants typically identified strong feelings of closeness with their partner, often exchanging contact information and indicating a wish to meet up again. “In the original [1997] experiment we also tested an intense version of this with cross-sex couples,” Aron said in Wired in 2011. “And the first ones we tested fell in love and got married. And as of last year, when I last had contact with them, they were still together.”

The control group participants were paired up to engage in small-talk, never, obviously, to be heard from again.

“The effect is based on gradually escalating reciprocal self-disclosure,” Aron and his colleagues explained in their paper, The Experimental Generation of Interpersonal Closeness: A Procedure and Some Preliminary Findings. “So are we producing real closeness? Yes and no. We think that the closeness produced in these studies is experienced as similar in many important ways to felt closeness in naturally occurring relationships that develop over time. On the other hand, it seems unlikely that the procedure produces loyalty, dependence, commitment, or other relationship aspects that might take longer to develop.”

This maps to the distinct brain systems Fisher and her team have identified for mating and reproduction:

- The sex drive, which, as Fisher says, “evolved to get us out there looking for a whole range of partners. You can feel it when you’re just driving along in your car. It can be focused on nobody.”

- Romantic love, “that elation and obsession which evolved to enable us to focus our mating energy on just one individual at a time, thereby conserving mating time and energy.”

- Attachment, “that sense of calm and security you can feel for a long-term partner, evolved to enable you to tolerate this human being at least long enough to raise a child together as a team.”

Right now our “dating” technology is built for the very particular, accumulative drive of #1. Not surprising, perhaps, considering who is (stereo)typically doing the building, but this experience design choice has created a template for imitation.

Co-founder, Whitney Wolfe, left Tinder (under circumstances, outlined in a sexual harassment lawsuit, that read, in excruciating screencaps of text exchanges, like a self-fulfilling indictment of the kind of pathological culture the product encourages) and created…. Tinder. Actually, it’s called Bumble. The Sadie Hawkins of dating apps, on Bumble it’s only women who are able to initiate a conversation once both parties have opted in to a match. Which is pretty much a branding gimmick turned into a product feature. The main differentiator becomes the type of person who would self select to use an app brand that flaunts female agency. But beneath that surface distinction the basic product experience isn’t really a departure from the app its founder left.

“[We know] from our work that if you go and do something very novel with somebody,” Fisher says, “You can drive up the dopamine in the brain, and perhaps trigger this brain system for romantic love. Mystery is [also] important. You fall in love with somebody who’s somewhat mysterious, in part because mystery elevates dopamine in the brain, [which] probably pushes you over that threshold to fall in love.”

Love, as it turns out, can’t be automated. (Who knew?) It doesn’t result from meeting or sleeping with more people. In fact, just the opposite. Love is triggered in a moment when we are able to experience something special in one individual, as everyone else fades away. As Proust said, “It is our imagination that is responsible for love, not the other person.”

Love loves rarity, not surplus, and it might actually hate efficiency, hearting, as it does, the out of the ordinary and unexpected and novel and non-routine. But from swipe to sex, the relentless, grinding repetitiveness inherent in every aspect of the “swipe app” experience, sabotages the very mechanics that trigger the brain system for romantic love.

In 2013, I wrote that “our technology is turning all of us into objects.”

The ubiquitousness of cameras and social platforms on which to share their output has made us all re-conceive ourselves and one another as media products. We are all selfies. We are all profiles. We are all hashtags. And we can’t stop. Now we swipe through thousands of instant people. We learn nothing of them and share nothing of ourselves to be known. We strip ourselves down to anatomy and stare at each other with hollow, cuddle-host eyes, and we become invisible. Independent contractors in the sharing economy of sex.

There’s obviously all kinds of reasons for why we fall in love with one person rather than another, but if the conditions for generating interpersonal closeness can be recreated in, of all places, a lab experiment, and if the neural mechanisms for how romantic love works can be understood, then perhaps the technological desert we currently find ourselves on is not only, as Sales says a “cultural problem,” it’s an innovation problem.

Love knows what it likes, and we could be building tech engineered for it — creating a match between the research and the product experience, as it were. But we aren’t.

In a time when it’s legal to marry whomever you love, love itself has become an alternative lifestyle.

Fear.

“Anxiety is love’s greatest killer,” said Anaïs Nin.

In a 2014 survey by the American College Health Association, 54% of college students surveyed said that they had “felt overwhelming anxiety” in the past 12 months. An increase of 5% from the same survey five years earlier. Nearly all of the campus mental-health directors surveyed in 2013 by the American College Counseling Association reported that the number of students with severe psychological problems had escalated at their schools.

In tandem, as Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt write in The Atlantic, “A movement has been arising at America’s colleges and universities, driven largely by students, to scrub campuses clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense,” (emphasis added).

Unlike the political correctness movement of the 80’s and 90’s, which sought to restrict hate speech aimed at marginalized groups, “the current movement is largely about emotional well-being; turning campuses into ‘safe spaces’ where young adults are shielded from words and ideas that make some uncomfortable.”

“Trigger warnings” — signaling that something potentially uncomfortable lies ahead — are now being “demanded for a long list of ideas and attitudes that some students find offensive. Books for which students have called publicly for trigger warnings within the past couple of years include Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart [for describing] racial violence, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby [for portraying] misogyny and physical abuse, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (at Rutgers, for ‘suicidal inclinations’), and Ovid’s Metamorphoses (at Columbia, for sexual assault). In an article published last year by Inside Higher Ed, seven humanities professors wrote that the trigger-warning movement was ‘already having a chilling effect on [their] teaching.’ They reported their colleagues’ receiving ‘phone calls from deans and other administrators investigating student complaints that they have included ‘triggering’ material in their courses, with or without warnings.’ A trigger warning, they wrote, ‘serves as a guarantee that students will not experience unexpected discomfort.’”

Shielding people from experiences that might cause them emotional discomfort, however, doesn’t help them actually overcome their anxiety. “According to the most-basic tenets of psychology,” Lukianoff and Haidt write, “The very idea of helping people with anxiety avoid the things they fear is misguided. A person who is trapped in an elevator during a power outage may panic and think she is going to die. That frightening experience can change neural connections in her amygdala, leading to an elevator phobia. If you want this woman to retain her fear for life, you should help her avoid elevators.”

And if you want a generation to fear of intimacy, then help them avoid feeling anything uncomfortable. For what could be more fundamentally discomforting than love?

“You know, if you ask somebody to go to bed with you, and they say, ‘No, thank you,’ you certainly don’t kill yourself or slip into a clinical depression,” Fisher says. But people who are rejected in love do. “We live for love. We kill for love. We die for love. It is one of the most powerful brain systems on Earth for both great joy and great sorrow.”

Trigger warning: Love will make you feel.

It’s telling that amidst the 6,000+ words about the sex lives of 21st century 20-somethings in Sales’ article, “love” makes an appearance just once: “What about the still-flickering chance that somebody might fall in love?” she asks.

“Some people still catch feelings in hookup culture,” Sales quotes Meredith, a Bellarmine sophomore. “It’s not like just blind fucking for pleasure and it’s done; some people actually like the other person. Sometimes you actually catch feelings and that’s what sucks, because it’s one person thinking one thing and the other person thinking something completely different and someone gets their feelings hurt. It could be the boy or the girl.”

It’s an interesting turn of phrase, “catch feelings,” that has pervaded our contemporary conception of ourselves. It connotes that feelings are a contamination, a sickness you contract, a disease of some kind. An STD.

“People acquire their fears not just from their own past experiences,” Lukianoff and Haidt write, “But from social learning as well. If everyone around you acts as though something is dangerous — elevators, certain neighborhoods, novels depicting racism — “ feelings “ — then you are at risk of acquiring that fear too. “

In a sense, both the Japanese celibacy syndrome, and the west’s “psychosexual obesity” can be seen symptoms the same viral fear of our feeling selves. After all, if it makes you feel nothing either way, does it really matter how much sex you’re having, or any at all? You could practically hear the Americans in Sales’ article straining for the word mendokusai. Both cultures have convinced themselves that emotional necrosis is the cure; it’s too much trouble to feel.

“Love possesses you,” as Fisher says, “you lose your sense of self. You can’t stop thinking about another human being. Somebody is camping in your head.” That kind of insurgent invasion on our prized individualism has come to seem beyond trouble: it’s terror.

Ironically, it is through exposure and acclimation to that which we fear that we reduce anxiety. By confronting the things we’re scared of and realizing we can handle them, we rewire the brain to associate previously feared situations with normalcy. Anxiety is literally the inability to cope with what we feel. If all we’re trying to do is avoid catching feelings, never learning how to live with them, it’s no surprise anxiety would be on the rise.

What happens when a generation so terrified of even just reading something that might make them feel uncomfortable they’ll voluntarily censor classic literature rather than cope with the emotions art stirs up collides with technology that reduces us all to objects? And what happens when the people creating our technology have grown up in that same environment, mirroring its emotional bankruptcy back to us via the products they create?

“Keep playing,” Tinder encourages whenever a user gets a match. On this platform for finally, truly “gamifying” sex, there’s no room for feeling. People are prizes and bodies are points and feelings don’t accrue you anything, so what’s the point of having them? They are inefficient and invisible. (You can’t even post a photo; did they happen at all?)

Maybe one day in the future we’ll invent technology for that too. Botox the bugs in the brain that feel grief or sorrow or loss or love. Lobotomize ourselves into an Eternal Sunshine state of mind. But in the meantime, we are still human, feeling beings, who increasingly view their own feeling nature as a contamination.

Imagine a 13 year old today. Too young to have ever known how it’s like to to fall in love or go on a date or be in a relationship — but old enough to be on Tinder. What will coming of age in this environment be like for them? Porn is already how an entire generation learns how to have sex. What will being swallowed up into a ceaseless stream of swipe-able sex objects teach them about how to love?

.

Loss.

“Who knows how to make love stay?” Tom Robbins asked in Still Life with Woodpecker:

1. Tell love you are going to Junior’s Deli on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn to pick up a cheesecake, and if loves stays, it can have half. It will stay.

2. Tell love you want a momento of it and obtain a lock of its hair. Burn the hair in a dime-store incense burner with yin/yang symbols on three sides. Face southwest. Talk fast over the burning hair in a convincingly exotic language. Remove the ashes of the burnt hair and use them to paint a moustache on your face. Find love. Tell it you are someone new. It will stay.

3. Wake love up in the middle of the night. Tell it the world is on fire. Dash to the bedroom window and pee out of it. Casually return to bed and assure love that everything is going to be all right. Fall asleep. Love will be there in the morning.