The story of the biggest transformation of our time has a marketing problem: no one knows it’s happening.

There were many important events that happened in 2016. Some were deafening, trumpeting the seemingly inexplicable ascent of backwards-facing forces. But one event of great historical significance went largely unremarked upon.

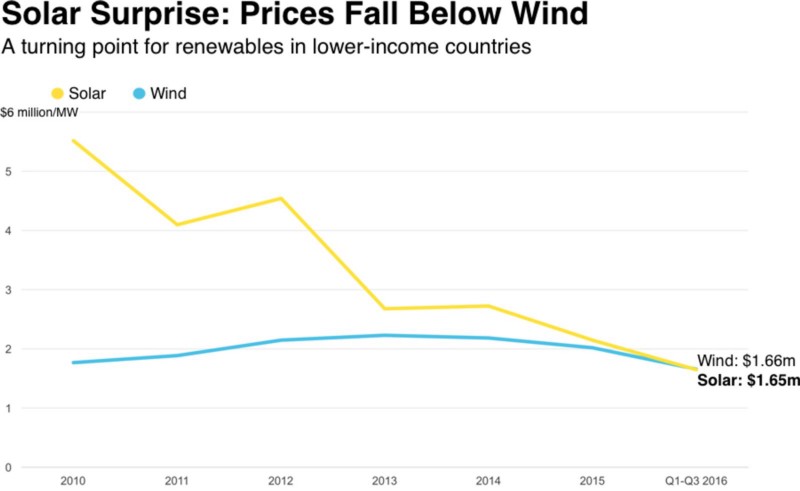

In 2016 solar power became the cheapest form of new electricity on the planet and for the first time in history installed more new electric capacity than any other energy source.

Amid the sepia haze oozing from the past’s rusting, orange pipeline, humanity was placing a serious bet on a new kind of future. And you didn’t even know about it.

That’s a problem.

Powering Disruption

It was a bit like if you had a source of whale blubber in the 1840s and it could be used as fuel. Before gas came along, if you traded in whale blubber, you were the richest man on Earth. Then gas came along and you’d be stuck with your whale blubber. Sorry mate — history’s moving along.

— Brian Eno

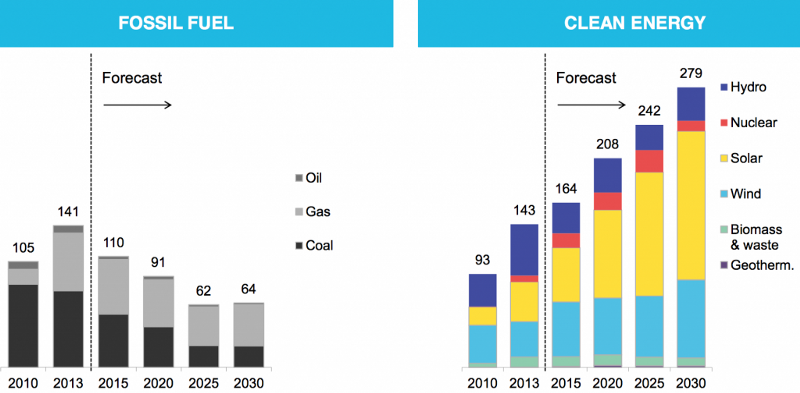

“The beginning of the end for fossil fuels,” according to Bloomberg, occurred in 2013. “The world is now adding more capacity for renewable power each year than coal, natural gas, and oil combined. And there’s no going back…. The shift will continue to accelerate, and by 2030 more than four times as much renewable capacity will be added.”

The International Energy Agency’s Executive Director, Fatih Birol, said, “We are witnessing a transformation of global power markets led by renewables.”

“While solar was bound to fall below wind eventually, given its steeper price declines, few predicted it would happen this soon,” notes Bloomberg.

In the United States, as coal production fell an estimated 17% in 2016, continuing an 8 year decrease, the solar market nearly doubled, breaking all records and beating oil, coal, and natural gas as the country’s biggest source of new electric generating capacity. While it’s still just a tiny fraction of the domestic electricity mix, in 2016 40% of all new capacity additions came from solar. 2016 was also the 4th consecutive year that US solar jobs grew by more than 20%, according to the Solar Foundation. One out of every 50 new jobs added in the United States in 2016 was created by the solar industry, which now employs more people than oil, coal, and gas extraction combined.

“Solar investment has gone from nothing — literally nothing — like five years ago to quite a lot,” said Ethan Zindler, head of U.S. policy analysis at BNEF. “A huge part of this story is China, which has been rapidly deploying solar” and, Bloomberg notes, helping other countries finance their own projects.

Between 2008 and 2013, solar panel costs dropped by 80% worldwide thanks to the accelerant of Chinese manufacturing. As Scientific American writes:

China leapfrogged from nursing a tiny, rural-oriented solar program in the 1990s to become the globe’s leader in what may soon be the world’s largest renewable energy source.

According to DOE, the [Chinese] federal government was willing to chip in as much as $47 billion to help build its solar manufacturing into what it calls a “strategic industry.”

In building up the world’s largest solar manufacturing industry, one that became the price leader in most aspects of the world’s market — beginning with cheaper solar panels — China helped create a worldwide glut. [In 2013] there were roughly two panels being made for every one being ordered by an overseas customer.

By 2015, China’s domestic market bypassed Germany’s to be the largest in the world…. [Today] China dominates the solar market in PV installation as well as total installed capacity, with the United States a distant third and fourth, respectively.

“If there was ever a situation where the Chinese have put their whole governmental system behind manufacturing, it’s got to be solar modules,” [Ken] Zweibel [30-year veteran of the U.S. solar industry and DOE] said.

“They fundamentally changed the economics of solar all over the world,” said Amit Ronen, director of the Solar Institute of George Washington University.

The impact of cheap, abundant solar technology has begun to ripple out across a planet where, as Scientific American notes, “the mathematics have long shown that solar power is the most abundant energy resource.”

In 2016 Sweden announced it’s committing to becoming 100% renewable by 2040. India broke a world record with a 6 square mile-wide solar farm, and set its sights on doubling its solar power capacity. In January, Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest crude oil exporter, announced a plan to invest $163 billion in renewables to support 50% of the country’s energy needs by 2050. Although admittedly their goal is to free up more oil for export in the short term, the country’s fate, The Atlantic reports, “may now depend on its investment in renewable energy.”

Before 2016 came to a close, China announced plans to cancel over 100 coal plants in development and to create 13 million jobs in renewables over the next 4 years. (For context, the US clean energy industry is just over 3 million jobs. The entire US tech industry is 6.7 million jobs.)

“The question is now no longer if the world will transition to cleaner energy,” FastCompany writes, “but how long it will take.”

According to the International Energy Agency, while solar makes up less than 1% of the electricity market today it could be the world’s biggest single source by 2050

Already, The Wall Street Journal reports, energy companies are beginning to confront the “crude reality… that some fossil-fuel resources will remain in the ground indefinitely.”

“A Goldman Sachs report last year forecast solar and wind will generate more new energy capacity in the next five years than the shale-oil revolution did in the last five,” writes David Bank, of ImpactAlpha.

Bloomberg predicts peak fossil-fuel use for electricity may be reached within the next decade. Peak gasoline demand by 2021.

“For over 100 years, the oil industry and its stakeholders have believed that the market for their products will continue to grow ad infinitum without competitive challenges,” energy economist, Peter Tertzakian wrote last month. “Never in my 35-year career following energy markets has there been so much widespread disagreement about future demand for oil.”

From the water’s edge of 2017 we can see out onto the horizon. When the future history books are written, 2016 will be the year the tide turned.

Why didn’t we realize it?

Powering Denial

“For as I detest the doorways of Death, I detest that man, who hides one thing in the depths of his heart, and speaks forth another.”

— Achilles, The Iliad

“We live in the Stone Age in regard to renewable power,” Florida state Rep. Dwight Dudley, said last year in Rolling Stone’s expose on the war entrenched utilities are waging on solar energy. “The power companies hold sway here, and the consumers are at their mercy.”

Rate hikes and punishing fees for homeowners who turn to solar power [have] darkened green-energy prospects in could-be solar superpowers like Arizona and Nevada. But nowhere has the solar industry been more eclipsed than in Florida, where the utilities’ powers of obstruction are unrivaled… .The solar industry in Florida has been boxed out by investor-owned utilities (IOUs) that reap massive profits from natural gas and coal… .These IOUs wield outsize political power in the state capital of Tallahassee, and flex it to protect their absolute monopoly on electricity sales.

The rise of distributed solar power poses a triple threat to these monopol[ies]. First: When homeowners install their own solar panels it means the utilities build fewer power plants, and investors miss out on a chance to profit. Second: Solar homes buy less electricity from the grid; utilities lose out on recurring profits from power sales. Third: Under “net metering” laws, most utilities have to pay rooftop solar producers for the excess power they feed onto the grid. In short, rooftop solar transforms a utility’s traditional consumers into business rivals.

The utility trade group Edison Electric Institute (EEI) warns that rooftop solar could do to the utility industry what digital photography did to Kodak, bringing potentially “irreparable damages to revenues and growth prospects.”

Few industries are worse equipped to deal with disruption than power utilities. Their profits depend on infrastructure investments that pay off over a generation or more. “Utilities are structured to be in stasis,” says Zach Lyman, partner at Reluminati, an energy consultancy in Washington, D.C. “When you get fully disrupted, you’ve got to find a new model. But utilities are not designed to move to new models; they never were. So they play an obstructionist role.”

Obstruction plays out in the State Houses, but it also plays out in hearts and minds. Here’s what obstruction looks like as a messaging strategy:

Bills percolating through state legislatures across the U.S. are giving the education fight a new flavor, by encompassing climate change denial and serving it up as academic freedom.

— Newsweek

And so on.

But behind the petroleum-jellied lens of blurry obstructionism “Freedom” is just a marketing gimmick when you’ve got nothing left to lose except your entire whale blubber fortune.

As futurist Alex Steffen explains:

There is no long game in high-carbon industries. Their owners know this. They don’t need a long game, though… . All they need is the perception of the inevitability of future profit, today. That’s what keeps valuations high… .The Carbon Bubble will pop not when high-carbon practices become impossible, but when their profits cease to be seen as reliable.

For high-carbon industries to continue to be attractive investments, they must spin a tale of future growth. As it becomes clear that these assets will not produce profit in the future, their valuations will drop — even if the businesses that own them continue to function for years. The value of oil companies will collapse long before the last barrel of oil is burned.

Put another way: The pop comes when people understand that growth in these industries is over and that, in fact, these industries are now going to contract. That’s when investors start pulling out and looking for safer bets. As investors begin to flee these companies, others realize more devaluation is on the way, so they want to get out before the drop: a trickle of divestment becomes a flood and the price collapses. What triggers the drop is investors ceasing to believe the company has a strong future.

“Gridlock is the greatest friend a global warming skeptic has,” a spokesman for an Oklahoma senator says in Jane Mayer’s Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right. “That’s all you really want. There’s no legislation we’re championing. We’re the negative force. We are just trying to stop stuff.”

The energy generated by the obstruction force of the most powerful industry that has ever existed on the face of the Earth has created such friction it has ground our sense of the future a halt. The lights keep dimming on us and we don’t know why. The gears of culture groan precariously against grinding, backwards momentum. The crude, snake oil slogans peddling past glory are so bleakly recursive they erase the very idea of future. And that is no coincidence. Carbon has a stake in wiping the future out of our imaginations. Because in the Future the world pivots.

Powering Destiny

One of these mornings

It won’t be very long

They will look for me

And I’ll be gone.

— Patti LaBelle

This past October, Liu Zhenya, the former chairman of China’s state-owned power company, State Grid Corp., came to the United Nations to present a vision for what a post-carbon Future would look like. He described a global power grid that could transmit 80% renewable energy by 2050, Scientific American reports.

His speech invited U.N. support for a new international group to plan and build the grid. It’s called the Global Energy Interconnection Development and Cooperation Organization (GEIDCO), and China has named Liu its chairman. [This] global grid would transmit solar, wind and hydroelectric-generated power from places on Earth where they are abundant to major population centers, where they are often not.

His grid’s development would take shape in three phases. First, Liu explained, individual nations would redesign their own power electric grids. He noted that China’s effort is already underway, generating 140 GW of wind power and 70 GW of solar power, “more than that of any country of the world.” By completing a network of long-distance, high-voltage direct-current power lines to move renewable power from the north to the south and from the east to the west, China could finish its new grid by 2025, he predicted.

The second phase, Liu described, would be an international effort to build regional grids that would be able to transmit substantially more power across national borders in Northeast and Southeast Asia, between Africa and Eurasia, and between nations in both North and South America. The third phase would build power lines and undersea cables that would connect the regional grids. The upshot would create what he called a “win-win situation.”

There would be plenty of work for “all global players” to coordinate the effort, to share and innovate new technology, and to develop global standards and rules for cooperation, Liu promised. He closed his U.N. presentation with a glimpse of a future world where a combination of renewable energy, a network of high-voltage direct-current transmission lines and “smart grid” operating systems can serve the planet the way the human “blood-vascular system” serves the human body.

When the global grid is completed, “the world will turn into a peaceful and harmonious global village with sufficient energy, green lands and blue sky,” he predicted.

Is it kooky that the Chinese would be talking about World Peace on the eve of 2017? Sure. But the thing is — that could have been us.

In the 1960’s, American architect and systems theorist, Buckminster Fuller created the World Game project. An alternative take on the war game simulations that dominated the Cold War era, the World Game requires participants to solve the following problem: “Make the world work for 100% of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone.”

“The global energy grid is the World Game’s highest priority objective,” Fuller wrote.

Half a century after this idea of a distributed energy Future first emerged out of the American counterculture, a representative from the world’s second largest economy just presented it at the United Nations as the vision for his country’s energy ambitions.

“We argue so much about the silly politics of climate change and fail to recognize the gargantuan economic opportunity that this presents,” says Gregory Wilson, co-director of DOE’s National Center for Photovoltaics. “The energy system is going to get re-engineered, and someone is going to do it. The Chinese seem to have recognized the significance of this opportunity.”

Last year China invested a record $32 billion in overseas renewable energy projects. A 60% increase from the year before. Over the next 4 years the Chinese plan to to invest $360 billion in renewables domestically to boost capacity by 500%. The rapidly accelerating innovation that this kind of financing unleashes creates global market forces that may have their own momentum. From radically reimagined (and profoundly cheaper) battery technologies to printable solar panels that could transform “nearly any surface into a power generator” to electric busses that can go 350 miles on a single charge, new pieces of this vast puzzle seem to be emerging almost daily.

“Eventually,” Vox’s David Roberts writes, “power generation and storage will become ambient, something that simply happens, throughout the urban infrastructure. With that will come more and more sophisticated software for managing, sharing, and economizing all that power. [This] will one day change the world as much as the internet has.”

Indeed, as TechCrunch writes: Energy is the new Internet.

An undeniable, distributed energy Future powered by solar and other renewable sources is emerging. Perhaps the only Future on offer in the 21st century thus far that presents a bright vision worth striving for.

And yet — from a consumer perspective, solar energy seems to have no idea what it’s really selling.

Powering Desire

“If you don’t like what is being said, then change the conversation.”

— Don Draper

“In 2008, when fracking was still just a tiny thing, Davos was crowning it as the start of a new world order,” clean energy entrepreneur, Jigar Shah said recently on the Energy Gang Podcast. Yet solar is still considered “just a tech thing,” he lamented. “We’re not Earth shattering.”

Where does the momentum for a movement come from, Shah wondered? Why is solar perceived as just some sort of… appliance? Why, despite breaking records and reshaping trend-lines the world over in 2016, isn’t solar getting the kind of buzz befitting one of the biggest stories of our time?

Because messaging.

Here is how SolarCity, the largest residential solar installer, positions its product:

“Our solar panels not only generate energy on your roof, they can also generate cash in your pocket. That’s because when you go solar you can save on your monthly utility bill and secure lower fixed energy rates for years to come. The savings over time add up and allow you to plan for your future. See how quality, savings and affordability make going solar the right choice.”

Solar is the Future but you’d never know it from the way it’s marketed. And this commoditized framing is reflective of the industry as a whole. The retail model for solar hasn’t changed from what it was a decade ago. But the world has. The internet is on our doorstep but solar is still selling people on the value prop of word processors.

Compounding the messaging problem, solar is still positioned as an “alternative.” Droga5’s campaign for NRG Home Solar still presents renewable energy as an option relative fossil fuels. (Perhaps inevitable given the nature of NRG’s legacy-fuel masters.)

Both of these misguided approaches are a drag on the industry’s true potential. Solar isn’t a gadget, or an alternative lifestyle — it is an entry point to the new Future. In 2017, the territory of a desirable Future is totally unclaimed white space in consumer consciousness and the solar industry is uniquely positioned to own it.

Here’s how:

– Industry-level Messaging Platform –

In the 1990’s the Got Milk? campaign gave a commoditized product the status of a cultural icon. Executed at a trade level by the American dairy farmers, the industry-wide platform created a bigger impact than could have been possible for any dairy producer individually.

Like milk, energy is not a sphere with recognizable consumer brands that are part of the larger cultural conversation. The one notable exception, of course, is Tesla, which dropped the “Motors” from its name when it acquired SolarCity at the end of 2016. Analysts insisted that this acquisition is an “unneeded distraction,” and that Tesla ought to be “singularly focused on becoming a mass automobile manufacturer,” but that is a shortsighted view for a company that now makes solar panels and energy storage products. When it comes to Tesla’s true ambitions, as CEO, Elon Musk puts it, “We need a revolt against the fossil fuel industry.”

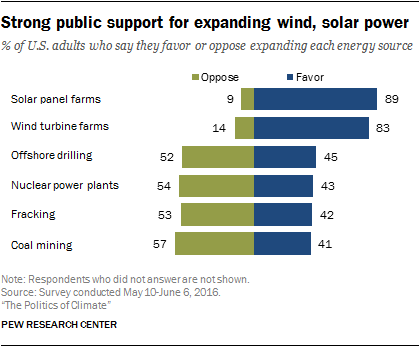

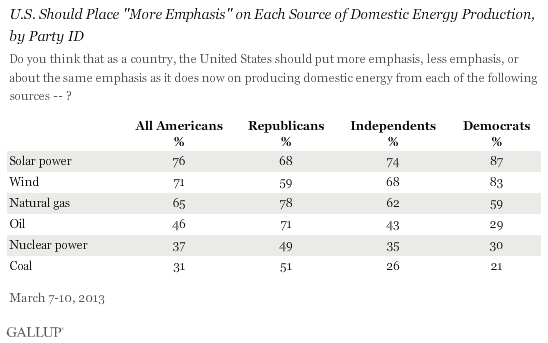

Everything Tesla does unequivocally insists, desirable Future, but there is enough shine for the entire industry to own. At the end of the day, it’s solar itself that consumers have an affinity for —

Even among the majority of all political affiliations, no less—

It doesn’t take a moonshot PR campaign to capitalize on this abundance of positive consumer sentiment. Just a cohesive voice with which to claim the message and consistently speak it into the culture.

– Expand the Target Audience –

Everyone in solar is targeting the same homeowner and business audience. A vastly unexplored area is strategic ways to engage literally everyone else.

In 2008 I wrote about Toyota’s integration with Whyville, an online virtual world for tweens:

Pretty much the coolest thing you can buy in Whyville is a Scion, and its added bonus is that then you can drive all your other friends around in it in the game. The most fascinating thing about this whole strategy, however, is that the Tween demographic is between 8–12 years old. It’s gonna be a while before they even have a driver’s license, let alone be in a position to be buying a car in the real world, but when they are, they will already have a virtual experience to draw on when making the purchase decision.

As the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center shows with its Clean Energy Activity Day program for elementary and middle school students, this approach doesn’t need to just be virtual.

From group purchasing at a community level to modular options for renters to innovative uses for incentive programs and student grants, and more, what are the actionable and scalable strategies for expanding the target audience and the bottom line across the solar industry?

– Sell the Experience –

Most people don’t really want to think about energy. We flip a switch and the electricity is just there. We interact with electricity literally all day, and never think about it. The narrative of distributed, storable, smart-gridded, clean energy is so profoundly different from what most people know, or know how to think about, for them to understand it — or even want to — requires a transformative shift in the way it is communicated.

When Apple first marketed the iPod, it didn’t sell the product, they sold its end result — the experience of music:

Later campaigns for the iPhone didn’t even show the product at all:

The product became the conduit to the experience. And the experience that solar has to sell is Future.

– Claim the Narrative of Future –

Two decades ago — back when it was still possible to talk about the future as anything but dystopia — a series of ads painted a striking vision of how that future was going to unfold. “Have you ever borrowed a book from thousands of miles away,” asked the ad voice. “Crossed the country without stopping to ask for directions? Or watched the movie you wanted to, the minute you wanted to?”

“You will,” said the voice, “and the company that will bring it to you: AT&T.”

Today I use a device to do basically 90% of what those ads predicted. (OK, I’ve never sent a fax from the beach, or tucked a baby in from a phone-booth, but you can’t get the Future 100% right). All of these things are so obvious and mundane now we barely even remember — some of us never knew — there was a time before. But, indeed, there was a point when this fantastical world was the future, and the future still seemed like a fantastical world.

There are no grand visions for the future now, no scenarios for humanity that don’t fill us with dread. A dying oligarchy tells us dissolution is freedom; regression is hope. It has disfigured our understanding of what’s happening in our world. The result is a gaping void in our collective vision when we look ahead. 17 years in to our new century there is a desperate hunger for a bright vision for the future, and at the moment arguably no one outside the world of clean energy has a legitimate claim to one. In the end, it’s not about utility bills or net metering laws or even solar panels for that matter. It’s about a vision of a Future worth demanding. Solar has the opportunity to be the voice of that vision for decades to come with a simple, cohesive, culture-focused messaging strategy.

Mirrorgram by:

Mirrorgram by: