Our technology is turning us all into objects. And it doesn’t matter how you treat objects, does it?

I have been responsible for more selfies than most people.

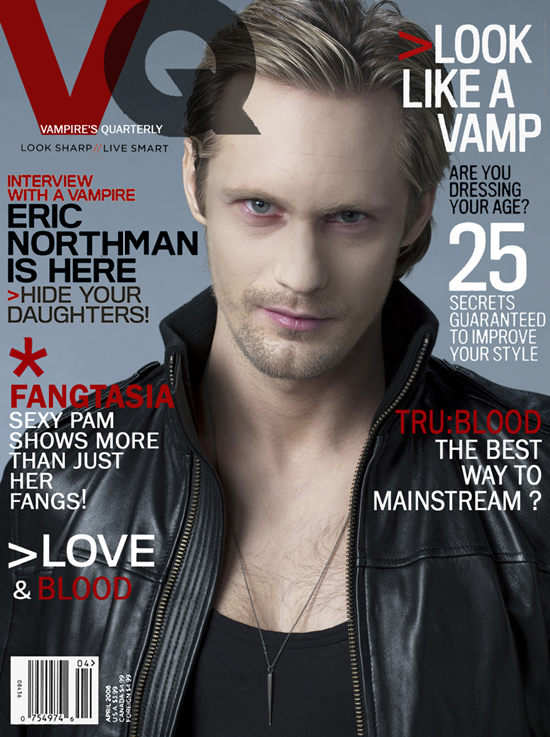

I didn’t take them. They’re not of me. But I launched an app which allows users to easily create mirrored images. So the leap from this:

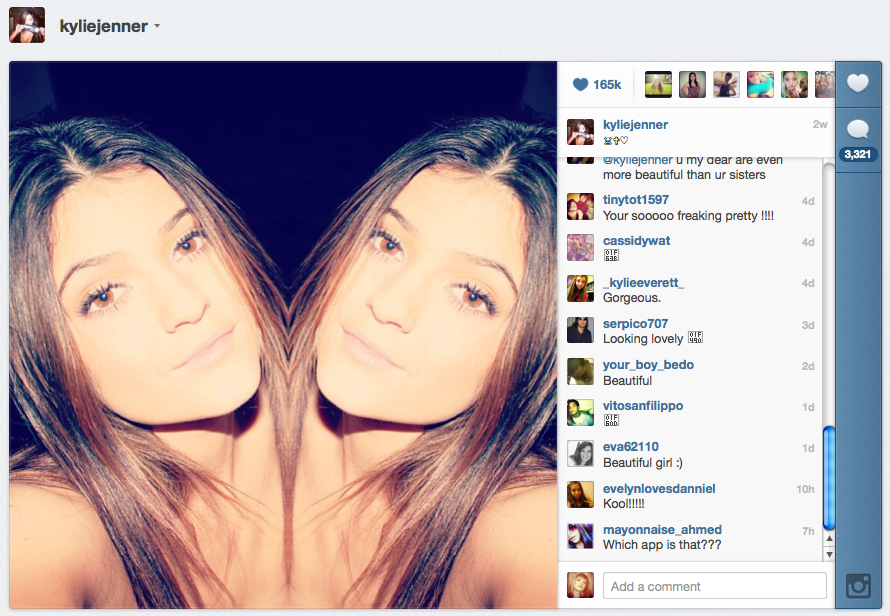

To this:

Was almost instant.

In the year since our app launched, our users have created over 5 million images. By now you’ve seen this mirrored selfie trend all over Instagram, not to mention throughout the greater popular culture.

To be fair, mirrored selfie-grams are far from the only way people engage with the app. They also use it to create stunningly beautiful, painstakingly crafted, kaleidoscopic works of abstract art:

But it’s the selfies — mirrored or otherwise — that have been on my mind a lot lately.

Selfies.

Right now, there are 50 million images on Instagram with the hashtag #selfie, and nearly 140 million tagged #me.

“Selfies,” Elizabeth Day reports in the Guardian, “Have become a global phenomenon. Images tagged as #selfie began appearing on the photo-sharing website Flickr as early as 2004. But it was the introduction of smartphones – most crucially the iPhone 4, which came along in 2010 with a front-facing camera – that made the selfie go viral.”

A recent survey of more than 800 American teenagers by the Pew Research Centre found that 91% posted photos of themselves online – up from 79% in 2006.

But the selfie isn’t just a self-portrait, it is a self-object.

“Again and again, you offer yourself up for public consumption,” Day writes. “Your image is retweeted and tagged and shared. Your screen fills with thumbs-up signs and heart-shaped emoticons. Soon, you repeat the whole process, trying out a different pose.”

“The selfie is about continuously rewriting yourself,” says Dr. Mariann Hardey, a lecturer in marketing at Durham University who specializes in digital social networks. “It’s an extension of our natural construction of self.”

But what is it we are constructing our selves into?

Porn.

Before we go any further, let’s get this out of the way: unless you are a teenager right now, you do not understand what it means to grow up in a world where porn and Facebook are equidistant — in case you don’t know, that proximity is one click away, and apart. If you’re curious to understand what, in fact, this experience is like — in teenagers’ own words — you should read Nancy Jo Sales’ recent Vanity Fair article, “Friends Without Benefits.” But not until after you’ve finished reading this one because I’ll be drawing on it quite a bit.

If you are, at this moment, older than at least your mid-20s, whatever it is that you think you can draw on to relate to 2013 from an analog adolescence frame of reference, just put that away, because it is not a parallel to what is happening right now. What is, according to Gail Dines, the author of Pornland: How Porn Has Hijacked Our Sexuality, is “a massive social experiment.” Here are some results from that experiment so far:

- 90% of all pornography now comes from the Web (University of Montreal)

- There are 24.6 million porn sites, or 12% of the entire web (Gizmodo)

- TheDailyBeast recommends you might want to be there when your child searches: “My Little Pony.”

- 30% of U.S. teenagers are sending nude photos over e-mail or texts (University of Texas Medical Branch)

According to a 2008 CyberPsychology & Behavior study:

- 93% of boys and 62% of girls have seen internet porn

- 83% of boys and 57% of girls have seen group sex online

- 18% of boys and 10% of girls have seen rape or sexual violence

But that was five iPhone versions ago at this point, so, you do the math.

“In the absence of credible, long-term research, we simply don’t know where the age of insta-porn is taking us,” writes Peggy Drexler on TheDailyBeast, but that we are in it, and that it is pervasive, is undeniable.

“What does this do to teenagers,” Sales asks in Vanity Fair. “And to children? How does it affect boys’ attitudes toward girls? How does it affect girls’ self-esteem and feeling of well-being? And how is this affecting the way that children and teenagers are communicating on these new technologies?”

In the the Guardian, Day describes one typical answer to that last question: “The pouting mouth, the pressed-together cleavage, the rumpled bedclothes in the background hinting at opportunity — a lot of female selfie aficionados take their visual vernacular directly from pornography (unwittingly or otherwise).”

“Because of porn culture,” says Dines, “Women have internalised that image of themselves. They self-objectify.”

“The girls I interviewed,” says Sales, “Even if they’re not doing it themselves, it’s in their faces: their friends posting really provocative pictures of themselves on Facebook and Instagram, sending nude pictures on Snapchat. Why are they doing this? Is this sexual liberation? Is it good for them? Girls know the issues, and yet some of them still can’t resist objectifying themselves, as they even talk about [themselves]. As the girl I call ‘Greta’ says, ‘more provocative equals more likes.’ To be popular, which is what high school is all about, you have to get ‘likes’ on your social-media pics.”

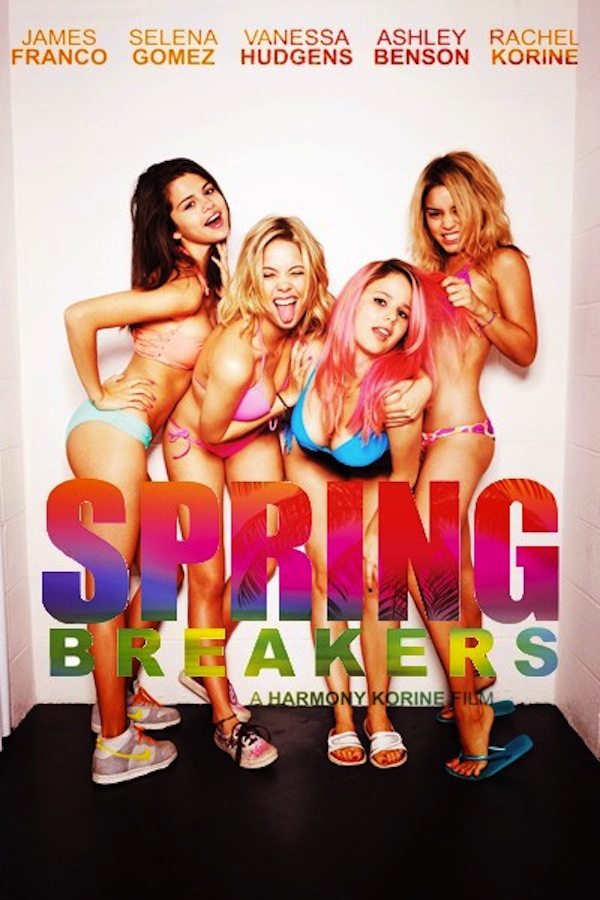

Spring.

Harmony Korine’s, Spring Breakers, originally released in March, 2013, “Horrifies and entices in equal measure,” wrote NPR music critic, Ann Powers:

Flattening the hierarchies that separate trash from art, porn from erotica, and moral justice from exploitation by any means necessary, Spring Breakers… embraces and elaborates upon the prevalent suspicion that nobody lives on the stable side of reality any more.

“Pretend you’re in a videogame,” says one of the film’s female anti-heroines as they begin their spree of rampant self-abuse and crime. That’s what Miley Cyrus does, trying on new aspects of performance and sexual self-expression in her new persona. It’s also how the vulnerable models that Robin Thicke ogles [in the music video for his song, Blurred Lines] make it through the gauntlet that the video’s scene creates.

The childlike goofiness Katy Perry expressed with California Gurlz in 2010, or the sweet hope of Carly Rae Jepsen’s smash of last year, Call Me Maybe, have intensified into something more unsettling. In this strange summer of too much heat, so many precariously excessive songs and videos now play on that line between healthy catharsis and chaos.

Summer.

The summer would get stranger still. Punctuated in its final days by what may just be the most controversial MTV Video Music Awards performance of all time, featuring a duet by Cyrus and Thicke.

From its very first steps, Cyrus’s performance felt, unmistakably, like watching a GIF happen in real-time. The act was speaking the native tongue — stuck all the way out — of the digital age, its direct appeal to meme culture as blatant and aggressive as the display of sexuality. The source material and its inevitable meme-ification appeared to be happening simultaneously. The Internet was inherently integrated within the performance. It was no longer a “second” screen; it was the same damn screen. All the performances before it had been made for TV. This show changed that.

What I learned from the 2013 VMAs is that owning your sexuality is passé, but owning meme culture by exploiting your sexuality is now. Whatever you think of it, Cyrus’s performance was a deliberate reflection of where we are as culture.

A burner had been left blindly on. Something invisible and pervasive had accumulated. Watching the VMAs, a giant fireball exploded in our faces.

We were unprepared.

This, ultimately, would be why everyone freaked out. Cyrus became a highly visible target for embodying this shift on a mainstream stage, and exploiting it to increase her fame and drive her record to #1, but all she was doing was deftly surfing the cultural current.

By the end of August, she was exposing us to the new normal.

Fall.

“In news that’s not at all surprising, yet another tech event was disrupted by a sexist joke,” Lauren Orsini wrote on ReadWriteWeb, within days of the VMAs:

“Titstare” was the first presentation of the TechCrunch Disrupt 2013 hackathon. Created by Australians Jethro Batts and David Boulton, the joke app is based on the “science” of how sneaking a peek at cleavage helps men live healthier lives.

The opening salvo cast an ugly shadow over the event, reminding attendees that, just like at PyCon and other technology conferences, “brogrammer” culture is still the norm.

Perhaps most disconcerting is the fact that Batts and Boulton presented immediately before Adria Richards, a programmer who rose to the national spotlight after she witnessed sexist jokes at PyCon 2013. Her gall to disapprove of the offensive jokes earned her death threats.

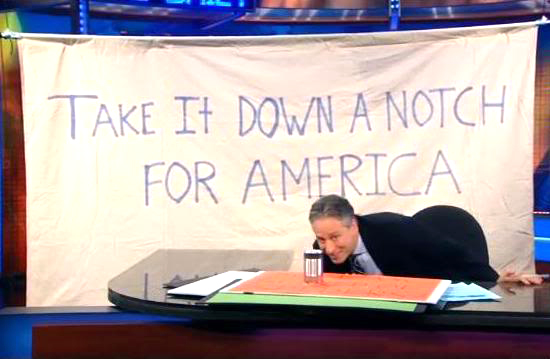

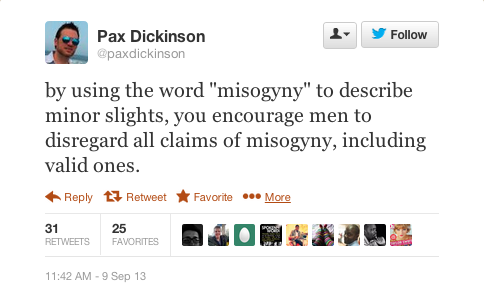

In the wake of the VMA article, I kept tweeting over and over, “Everything is changing….but into whatttttt?” By the early days of Fall, the culture had undeniably shifted. I kept kept seeing an escalating, atavistic gender warfare. Why is this happening, I thought.

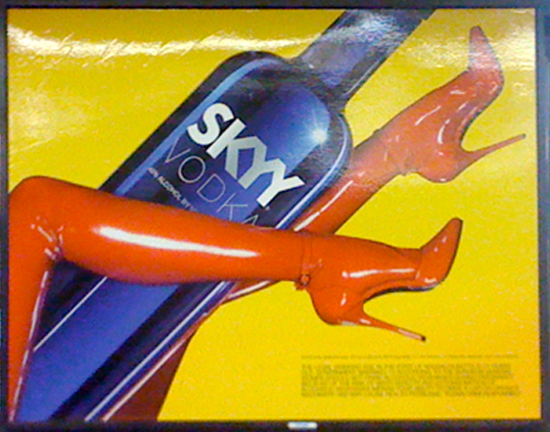

Why is this happening?

Why is THIS happening?

Why is THIS happening??

That all happened in one day.

That week I was approached to speak at a women’s startup conference and felt, reflexively, offended. The idea that there should be segregated events seemed insulting and damaging — to everyone. I began to feel self-conscious that I had an app startup with a male business partner. I texted him, “What is happening???” and “Can’t we all just get along?” We laughed, but we began to feel like an anomaly.

Pretend you’re in a videogame.

“When we listeners find ourselves taking pleasure in these familiar but enticingly refreshed acts of transgression,” Powers writes, “Echoing the Michael Jackson-style whoops that Pharrell makes in Blurred Lines, or nodding along to the stoned, melancholy chorus of Cyrus’s arrestingly sad party anthem, We Can’t Stop, are we compromising ourselves? Or is it okay, because after all, it’s just pretend?”

And when the technology that I, you, and everyone we know use on a daily basis gets developed to the sound of this same, blurry, pop culture soundtrack (figuratively or literally), what happens then? How are the creators of objectifying technology supposed to know it isn’t cool — if all of our technology is used for objectification?

In Vanity Fair, Sales talks to Jill Bauer and Ronna Gradus co-directors of Sexy Baby, a documentary about girls and women in the age of porn. “We saw these girls embracing this idea that ‘If I want to be like a porn star, it’s so liberating,’” Gradus said. “We were skeptical. But it was such a broad concept. We asked, ‘What is this shift in our sexual attitudes, and how do we define this?’ I guess the common thread we saw that is creating this is technology. Technology being so available made every girl or woman capable of being a porn star, or thinking they’re a porn star. They’re objectifying themselves. The thinking is: ‘If I’m in control of it, then I’m not objectified.’”

In October, Sinead O’Connor — whose video for Nothing Compares 2 U inspired Cyrus’s look in her video for Wrecking Ball — wrote an “open letter” to Cyrus, beautifully capturing, “in the spirit of motherliness and with love,” the generational disconnect at the heart of the cultural shift. “The message you keep sending is that it’s somehow cool to be prostituted.. it’s so not cool Miley. Don’t let the music business make a prostitute out of you,” O’Connor wrote, not getting it.

The familiar, analog, 20th century relationship in between objectification and commercialization has eroded. In its place, a new, post-Empire dynamic has arrived, built on a natively digital experience that O’Connor and an entire population still able to remember and relate to a world before the internet and mobile technology, can’t wrap their heads around.

“The blurred messages Thicke, Cyrus and others are now sending fit a time when people think of themselves as products, more than ever before,” Powers writes.

In the attention economy, self-exploitation is self-empowerment. We are all objects. We are all products. We are all selfies.

And we can’t stop.

“Social media is destroying our lives,” Sales quotes a girl in Vanity Fair.

“So why don’t you go off it?” Sales asks.

“Because then we would have no life.”

The ubiquitousness of digital cameras and social media platforms to share their instant output has not only turned the idea that objectification is violation into an anachronism, but self-objectification is now, as Powers, writes “part of today’s ritual of romance.” Nearly one in three teenagers is sending nude photos, after all.

Like the girls in Sales’ article, who tell her that “presenting themselves in this way is making them anxious and depressed,” but continue to do it anyway, we do not self-objectify because we’re in control. We self-objectify because it is the norm.

We self-objectify to rationalize, to placebo-ize that we had control in the first place.

We Can’t Stop.

“Both young women and young men are seriously unhappy with the way things are,” says, Donna Freitas, a former professor at Hofstra and Boston Universities, who studies hook-up culture on college campuses in her new book, The End of Sex (which Sales suggests, “might as well be called The End of Love.”)

Sales writes:

Much has been written about hook-up culture lately, notably Hanna Rosin’s The End of Men (2012) and a July New York Times article, “Sex on Campus: She Can Play That Game Too,” both of which attributed the trend to feminism and ambitious young women’s desire not to be tied down by relationships.

But Freitas’s research, conducted over a year on seven college campuses, tells a different story.

She describes the sex life of the average college kid as “Mad Men sex, boring and ambivalent. Sex is something you’re not to care about. They drink to drown out what is really going on with them. The reason for hooking up is less about pleasure and fun than performance and gossip—it’s being able to update [on social media] about it. Social media is fostering a very unthinking and unfeeling culture.”

College kids, both male and female, also routinely rate each other’s sexual performance on social media, often derisively, causing anxiety for everyone.

And researchers are now seeing an increase in erectile dysfunction among college-age men—related, Freitas believes, to their performance anxiety from watching pornography: “The mainstreaming of porn is tremendously affecting what’s expected of them.”

Or as ThoughtCatalog writer, Ryan O’Connell, (oh, hey, sup, a dude), put it, “This is how we have sex now:”

Porn has killed our imaginations. We sit and try to fantasize. We shut our eyes tight and think, ‘Wait, what did I used to masturbate about before porn? What image is going to turn me on right now?” But your brain gets tired and your genitalia isn’t used to working this hard so you open your reliable go-to porno and get off in two minutes. Later, you have trouble maintaing an erection during actual sex because your partner doesn’t look like a blow up doll from the Valley.

Our sex lives are having less and less to do with actual sex. Intimacy has morphed into something entirely more narcissistic. What used to be about making each other feel good and connecting is now about validation.

When sex does happen, when we finally make it through the endless hoops of text messaging, planning a date and actually sticking to it and you discover that you like this person (or could like them for an evening), it feels like an old faded photograph that’s been sitting in a shoebox at the bottom of your closet. “This orgasm feels like a vintage ball gown! Is this how people used to do it in the olden days?!” It’s terrifying!

In 2013, our phones are getting to have all the fun. They’re getting laid constantly while we lay naked in the dark, rubbing our skin, trying pathetically to get turned on by the feel of our own touch. We scroll through our camera and see a buffet of anonymous naked photos we’ve collected over the last few months for us to jack off to. Somehow, this has become enough for us. Getting off has become like fast food. It’s accessible, cheap, and most likely going to make us feel like shit after.

We are actively participating in the things that keep us from what we want. Feel good now, feel bad forever later. Stomachache stomachache, junk food junk food.

In a pervasively mediated culture, where porn primes our perception of ourselves and others, and our technology reduces us to selfies, objectification is inevitable.

And the trouble is — it doesn’t matter how you treat objects…. It’s not like they’re people.

What people want today is “to hurt one another” and “get back at the people that hurt them,” Hunter Moore, the founder of IsAnyoneUp.com, told Rolling Stone last October.

In a September article on The Verge titled, The End of Kindness, Greg Sandoval writes:

And Moore ought to know. He’s one of the pioneers of revenge porn, the practice of posting nude photos to the web of a former lover in an attempt to embarrass, defame, and terrorize.

While minorities and homosexuals are often targeted, experts say no group is more abused online than women. Danielle Citron, a law professor at the University of Maryland lays out some of the numbers in her upcoming book, Hatred 3.0. The US National Violence Against Women Survey reports 60% of cyberstalking victims are women. A group called Working to Halt Online Abuse studied 3,787 cases of cyberharassment, and found that 72.5% were female, 22.5% were male and 5% unknown. A study of Internet Relay Chat showed male users receive only four abusive or threatening messages for every 100 received by women.

Moore has sold his site but scores of wannabes are cropping up. A check of these sites shows that victims are almost always women. At Myex.com over 1,000 nude photos and new pictures are added nearly every day. Each post typically includes the name of the person photographed, their age, and the city they live in. The posts come with titles like, “Manipulative Bitch,” “Cheater,” “Has genital warts,” “Drunk,” “Meth User,” “This girl slept with so many other guys,” and “Filthy Pig.”

The Verge contacted several women found on some of these sites, including Myex.com. While all of them declined to be interviewed, they did acknowledge that the photos were posted without permission by an ex-boyfriend or lover. One woman said that she was trying to get the pictures pulled down and had successfully removed them from other sites because she was not yet 18 years old when they were taken (if her claim is accurate it would make the snapshots child pornography). She pleaded that we not use her name and asked that we not contact her again.

If the woman was upset and afraid, she has a right to be, says Holly Jacobs, 30, who has started a nonprofit organization dedicated to ending revenge porn and supporting its victims. Jacobs knows firsthand that these sites are killers of reputations and relationships. Three years ago, Jacobs was studying for her PhD in industrial organizational psychology and working as a consultant at a university when a former boyfriend began posting nude photos of her online. The embarrassment and terror was just the beginning. Jacobs’ ex sent copies of the photos to her boss and suggested she was sexually preying on students. Jacobs’ employers, fearing bad press, asked her to prove she didn’t upload the photos herself. She finally felt compelled to change her name (Jacobs is the new name).

In July The Washington Post published a story about men who post phony ads to make it appear as if their ex-wives or girlfriends are soliciting sex. One man, Michael Johnson II of Hyattsville, Maryland, published an ad titled “Rape Me and My Daughters” and included his ex-wife’s home address. More than 50 men showed up to the victim’s house. One man tried to break in and another tried to undress her daughter. Johnson was sentenced to 85 years in prison. His victim was physically unharmed but these ads can be lethal. In December 2009, a Wyoming woman was raped with a knife sharpener in her home after an ex-boyfriend assumed her identity and posted a Craigslist ad that read, “Need an aggressive man with no concern or regard for women.” Her ex and the man who raped her are both serving long prison sentences.

Winter.

While people, trapped as we are by our digital avatars, are increasingly being reduced to objects, our technology seems to be benefitting from a transference of humanity.

Spike Jonze’s new movie, Her, due out in December, is being called “science fiction,” but the “future” depicted in the trailer looks essentially indistinguishable from the reality we all find ourselves in today. In it, a melancholy man, played by Joaquin Phoenix, and a Turing test-approved virtual assistant program, voiced by Scarlett Johansson, fall in love.

“Unlike the science fiction of yesteryear,” writes David Plumb on Salon.com, “Her is not about the evolving relationship between humans and artificial intelligence. Instead, Samantha appears to be essentially a human being trapped in a computer. Her thus appears to be about programming the perfect woman who fits in your pocket, manages your life, doesn’t have a body (and thus free will), and has an off switch.”

Pretend you’re in a videogame.