i moved my blog and everyone disappeared! i’m really missing the three people who used to read this blog. where you at? if you come back, i’ll get you on the list. (bring a friend, and i’ll put you down +1).

in my previous post i wrote about how hip hop culture offered the first really racially desegregated lifestyle choice, and while in the primordial culture ooze of hip hop nightlife this hybridity was the result of a sort of fortunate accident, in the world of hip hop industry this was a very deliberate strategy. wrought, perhaps most famously, by the combined pioneering forces of russell simmons and rick rubin–you may have heard of this little record label the two started together called def jam if you haven’t been deaf for the past two and a half decades.

from Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation:

Russell was a Black executive able to bridge Black and white tastes like no one since Berry Gordy. He hired Adler. Rick was a Jewish music producer who understood how profoundly Herc, Bam, and Flahs’s insights could reshape all of pop music. He hired Bill Stephney. The staff for Def Jam was uniquely suited and highly motivated to pull off a racial crossover of historic proportions.

Stephney convinced his friends at rock radio to stay on Run DMC’s cover of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way,” even when the call-out research showed racist, “get the niggers off the air” feedback. He then succeeded in propelling the Beastie Boys onto rap radio, a feat no less difficult. By the end of 1986, their strategy had been perfectly executed. The Black group crossed over to white audiences with Raising Hell, then the white group crossed over to Black audiences with Licensed to Ill.

Forget busing, Adler thought. Hip-hop was offering a much more radical, much more successful voluntary integration plan. It was bleeding-edge music with vast social implications. “Rap reintegrated American culture,” Adler declared. Not only was hip-hop not a passing novelty, [he] told journalists, it was culturally monumental.

once upon a time, hiphop represented the next-stage in the evolution of a modern identity (consider that even madonna emerged from the hiphop scene incubated at the roxy), yet the promise of hiphop’s diversity was instead crushed under the genre’s globalization of, essentially, third-world values. hiphop became not the messenger of the polycultural future, but the harbinger of the blinged-out apocalypse.

you know… when MTV first launched, with it slate of rock and new wave programming, black artist were so systematically excluded that it was only after columbia university reportedly threatened to boycott the station that MTV finally relented and started playing michael jackson videos in 1983. at the time, michael jackson was considered the mainstream symbol of what was “black, urban, and dangerous.” 20 years later, michael jackson (the michael jackson of 20 years ago, i mean) is STILL the cross-genre, cross-race, cross-cultural ambassador to “everybody let’s dance.”

what the hell happened?! this was supposed to be hiphop’s birthright!

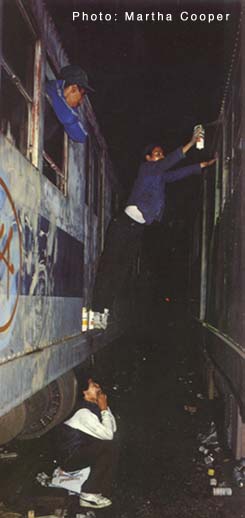

from the very beginning there were two ways this cultural expression could have gone. one direction was a bridge–like exactly what you’d expect from the first-generation american progeny of bob marley’s music being raised by kool herc and afrika bambaataa; as innate as the drive that propelled grafitti, as human as the beat that compelled people to dance. the other direction was as a flag. the loud proclamation of the marginalized and oppressed experience which had up till then been treated politically and culturally with a policy of “benign neglect,” and it was mad as hell and it wasn’t going to take it anymore. a voice that could speak for all who had had theirs stolen, with the sharpness of chuck d’s tongue or rakim’s rhyme. for both of these directions of hiphop the undercurrent of unification was an inherent component all along.

and then somewhere along the way hiphop exited too fast off the freeway and got itself twisted on a roundabout that sent it hurtling back into the complete opposite direction.

i’m not interested in discussing the polarizations that have gripped hiphop since, the violence, sexism, materialism, the east coast, the west coast, the gangsta rap, the conscious hiphop, the whatever, who cares. there’s a lot of talk about this already, and the bottom line is that the industry of culture is selling people what they want–whether it be kanye or lil john, or lil kim or lauryn hill, akon or talib. to deny consumers of something they’d pay money for would be bad business.

the real mystery at the intersection of culture and commerce is now this: in the age of the long tail of both demand and supply can we ever again expect an emergence of any kind of real, integrated culture? or is our destiny really just an endless assortment of choices that will turn our histories and mythologies into an ever more niche experience? will the accessibility of greater diversity lead to greater desegregation, or will it simply turn us into connoisseurs? content with the second-string substitute of globalization as a consolation prize for the cultural integration that never really arrived?

the spark that lit hiphop’s beginnings has been turned into hi-def dvd of a gas-powered fireplace crackling on a plasma-screen display.

but will the glimmer of hybridity that inspired it, ever be reincarnated in any other form?

– – –

more reaction to can’t stop won’t stop: a history of the hip hop generation:

HERE